Bob Dylan doesn't owe you anything. Not an explanation, not a straight answer, and certainly not a political ideology that fits neatly into a box. By 1983, the man who "electrified" folk music and then "found Jesus" was in a weird spot. He was drifting. The gospel years were cooling off, the synthesizers of the eighties were warming up, and out came Infidels. Right in the middle of that record sits Sweetheart Like You, a song that is either a tender ballad, a sexist jab, or a biting allegory for the state of the music industry.

It depends on who you ask.

The track is gorgeous. Mark Knopfler’s guitar work is clean, fluid, and melodic, providing a slicker backdrop than Dylan fans were used to. It’s got that classic "late-night-in-a-dim-bar" energy. But then you listen to the words. You hear Dylan rasping about a woman who doesn't belong in a "dump" like this. It sounds like a pickup line. Maybe it is. Or maybe, as many critics have argued for decades, the "sweetheart" isn't a woman at all.

What's Really Happening in Sweetheart Like You?

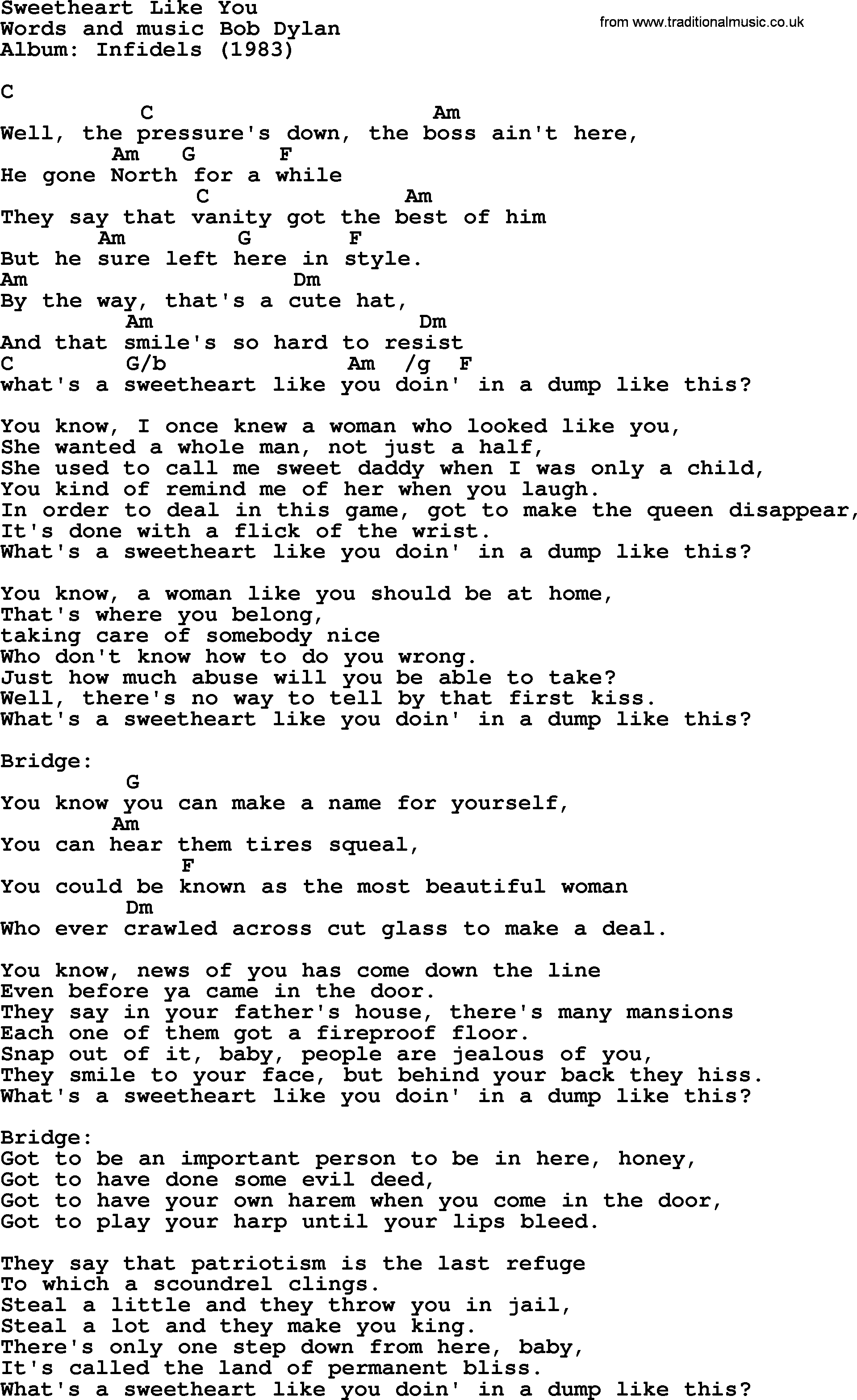

People get hung up on the "woman's place is in the home" line. It’s the elephant in the room. Dylan sings: "They say that patriotism is the last refuge / To which a scoundrel clings / Steal a little and they throw you in jail / Steal a lot and they make you king." Then, he drops the hammer: "A woman like you should be at home / That’s where you belong / Watching out for someone who loves you true / Who would never do nothing to wrong you."

In 1983, this went over like a lead balloon with some listeners.

Was he being a literal chauvinist? Some say yes. Dylan was coming off a period of intense religious conservatism, and his lyrics often reflected traditional, even archaic, social structures. But look closer at the context of Infidels. The album is obsessed with the decay of the world, the "neighborhood bully," and the shifting sands of morality.

There's a strong theory that the "sweetheart" is actually the Church—or perhaps the Muse itself—wandering into the filthy, commercialized world of the modern record business. Dylan is looking at something pure and wondering why it’s hanging out in a smoky dive bar with scoundrels. He's asking why something sacred is being sold for parts.

The Knopfler Influence

You can’t talk about this song without mentioning Mark Knopfler. The Dire Straits frontman co-produced the album and played lead guitar. He brought a precision that Dylan usually avoids. Usually, Bob wants to capture a "vibe" and move on. Knopfler wanted takes. He wanted perfection.

🔗 Read more: Love Island UK Who Is Still Together: The Reality of Romance After the Villa

The result is one of the most "professional" sounding tracks in the Dylan catalog. The solo on Sweetheart Like You is crystalline. It’s bluesy but polite. It contrasts sharply with Dylan’s vocal, which sounds like it was recorded after a long night of cheap cigars and even cheaper wine. That tension—between the polished music and the gravelly, cryptic delivery—is where the magic happens.

It’s almost too smooth. For some fans, the production felt like Dylan trying too hard to fit into the MTV era. But history has been kind to the song. It doesn't sound dated in the way other 1983 hits do. There are no gated reverb drums crashing over your head. It’s just a tight band playing a slow burn.

The Mystery of the Music Video

Let’s talk about the video. It’s bizarre.

Dylan is performing in a small, empty club. He’s wearing a leather jacket. He looks... uncomfortable? Maybe just bored. But the twist is the guitar player. Throughout the video, a woman is seen playing the lead guitar parts. However, she isn't actually playing. The audio is clearly Mark Knopfler.

This was a deliberate choice. Why have a woman "ghost-play" Knopfler’s parts on a song that tells a woman she belongs at home?

It’s classic Dylan trolling. He’s subverting the lyric visually. He’s showing you a woman in the "dump" (the club) doing the work of a master musician while his own voice tells her to leave. It’s a layer of irony that most people missed because they were too busy being offended by the surface-level lyrics.

Steal a Little, Steal a Lot

The most famous stanza in the song has nothing to do with romance.

💡 You might also like: Gwendoline Butler Dead in a Row: Why This 1957 Mystery Still Packs a Punch

"Steal a little and they throw you in jail / Steal a lot and they make you king."

This line has been quoted by everyone from activists to CEOs. It’s Dylan at his most cynical and observant. He’s talking about the Reagan era. He’s talking about the way power works. If you’re a petty thief, you’re a criminal. If you’re a corporate raider or a corrupt politician, you’re a hero of industry.

When you sandwich that kind of political bile inside a "love song," the love song ceases to be about a girl. It becomes a song about the corruption of everything. The "sweetheart" is the listener. Or the soul. Or the American Dream. Take your pick.

Why the Song Still Matters in 2026

We live in an era of "call-out culture" and intense scrutiny of lyrics. By modern standards, Sweetheart Like You should be "canceled." But it isn't. It remains a staple of classic rock radio and a fan favorite.

Why? Because it’s complicated.

Human beings aren't one-dimensional. Dylan’s writing reflects that. He can be tender and cruel in the same breath. He can be a prophet and a jerk. That’s why his work lasts. If this song were just a simple "I love you" ballad, we would have forgotten it forty years ago. Instead, we’re still arguing about what he meant by "at home."

Maybe "home" isn't a kitchen. Maybe "home" is a state of grace that the world has lost.

📖 Related: Why ASAP Rocky F kin Problems Still Runs the Club Over a Decade Later

Honestly, the song is a masterclass in songwriting because it forces you to take a side. You either accept the literal meaning and get annoyed, or you dig into the allegory and get lost in the maze.

How to Listen to It Today

If you want to actually "get" this track, don't just stream it on a loop.

- Listen to the "Infidels" version first. Notice the space between the notes.

- Compare it to "Blind Willie McTell." That’s the song Dylan famously left off the album. Why did he keep "Sweetheart" and cut a masterpiece? It tells you a lot about his headspace at the time. He wanted the "hit." He wanted the radio play.

- Read the lyrics without the music. It reads like a noir screenplay. There's a "hat hanging on the rack" and "maps" that don't lead anywhere.

Dylan was building a world. It’s a world of shadows and half-truths.

Actionable Insights for the Dylan Curious

If you're trying to deepen your appreciation for this era of Dylan's career, there are a few things you should do.

First, stop looking for a "correct" interpretation. Dylan himself has changed his tune on his lyrics a thousand times. He’s an unreliable narrator of his own life.

Second, check out the Springtime in New York Bootleg Series (Volume 16). It covers the 1980–1985 period. You get to hear the rehearsals and the alternate takes. You’ll hear Sweetheart Like You evolving. You’ll hear the band trying to find the groove. It strips away the 80s gloss and shows you the bones of the song.

Finally, pay attention to the rhyming scheme. Dylan uses internal rhymes and slant rhymes here that most songwriters couldn't pull off without sounding cheesy. The way he rhymes "last refuge" with "scoundrel clings" is clunky on paper but rhythmic as hell when he sings it.

The real takeaway? Don't take Bob Dylan literally. If you do, you're missing the point of being a fan. He’s a poet, and poets lie to tell the truth. Sweetheart Like You is a beautiful, frustrating, perfect lie. It’s a snapshot of a man trying to find his footing in a decade that didn't value his kind of wisdom anymore.

To dig deeper into the 1980s transition of folk legends, look into the production notes of the Power Station sessions. It reveals how Knopfler and Dylan clashed—and eventually collaborated—to create the specific sonic landscape of Infidels. Understanding the tension in the studio explains the tension in the track. That friction is exactly what makes the song endure.