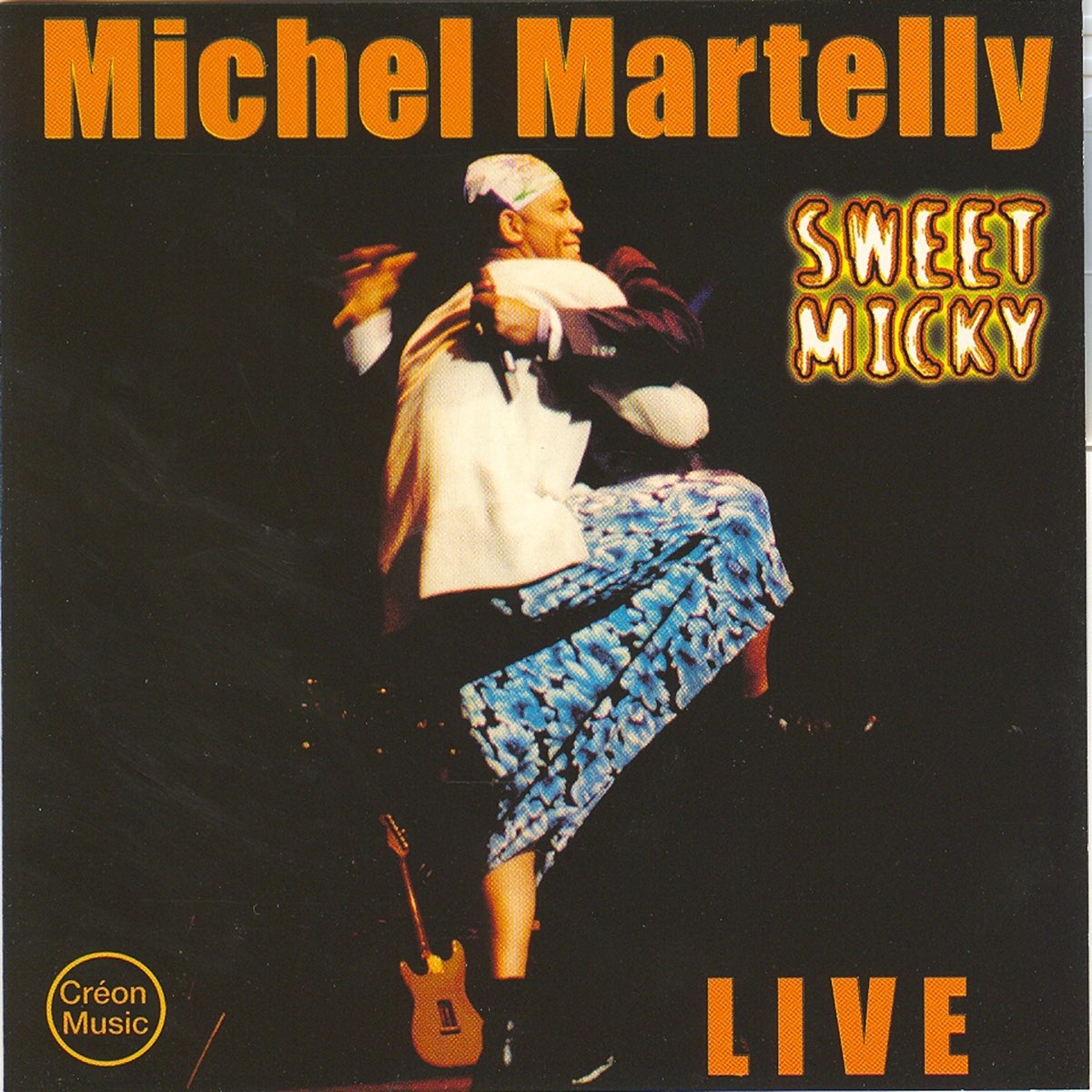

Michel Martelly is a name that carries two very different weights. To some, he’s the former President of Haiti who navigated the grueling aftermath of the 2010 earthquake. To everyone else—especially those who grew up on the sweat-soaked dance floors of Port-au-Prince or Miami—he is Sweet Micky. He was the "Bad Boy of Konpa," a man who performed in diapers, donned pink wigs, and mooned audiences without a second thought. But if you want to understand the exact moment his musical defiance started blurring into a political manifesto, you have to look at Sweet Micky I Don’t Care.

It’s not just a song. Honestly, it’s a mood that defined an entire era of Haitian defiance. Released during a time of immense political "free-fall" in the mid-90s, the track became a lightning rod for people who were tired of the status quo.

The Nihilism Behind the Beat

The mid-1990s in Haiti were, to put it lightly, chaotic. Jean-Bertrand Aristide had been ousted in a military coup, then returned to power with U.S. support. The country was split. On one side, you had the Lavalas supporters; on the other, the social elite and those nostalgic for the old regime.

Martelly didn't just pick a side. He danced on the line with a keyboard and a smirk.

Sweet Micky I Don't Care (or "Kimelem" in Creole) tapped into a very specific kind of "cheerful nihilism." While the political world was burning, Martelly was telling his audience that he didn't give a damn about the risks. The lyrics were often viewed as a direct jab at the Aristide government and the pro-Lavalas movement. He rapped about being at the "army headquarters," a move that was basically a middle finger to those who had suffered under the military junta.

🔗 Read more: Cry Havoc: Why Jack Carr Just Changed the Reece-verse Forever

It was provocative. It was dangerous. And people loved it.

Why the Song "I Don't Care" Changed Everything

Before this track, Martelly was just a talented musician making "New Generation" Konpa. He had ditched the big, 15-piece orchestras for synthesizers and drum machines, making the music cheaper to produce and louder to play. But with this era of music, he transitioned from a performer to a "sociopolitical activist"—even if that activism was rooted in trolling the government.

- The Sound: It wasn’t just the lyrics. The beat was infectious. It used that signature digital Konpa sound that invited people to forget their troubles, even if only for eight minutes.

- The Message: The phrase "I don't care" became a mantra. Whether you were from the slums of Cité Soleil or the mansions of Pétion-Ville, the song acted as a bridge. It said: everything is a mess, so let's just dance.

- The Persona: This was the peak of the "Sweet Micky" brand. He was wealthy, he was famous, and he was untouchable. Or so it seemed.

From the Stage to the Palace

You can't talk about the song without talking about how it paved the way for the presidency. In 2010, the album I Don't Care was re-released or heavily circulated right as Haiti was reeling from the earthquake. The timing was eerie.

Most people thought Martelly’s candidacy was a joke. How could the guy who sang about "not caring" lead a nation? But his "outsider" status was his biggest asset. People were tired of "serious" politicians who promised the world and delivered nothing. They figured, "We've tried the priests, we've tried the scholars. Let's try the clown."

💡 You might also like: Colin Macrae Below Deck: Why the Fan-Favorite Engineer Finally Walked Away

The irony is thick. The song that championed a lack of concern became the anthem for a man who eventually had to care about everything from cholera outbreaks to constitutional crises.

The Darker Side of the "Bad Boy"

It wasn't all just fun and games, though. Martelly's "I don't care" attitude often drifted into territory that many found repulsive. Throughout his career, and even into his presidency, he used his musical platform to target critics.

Take the 2016 track "Bal Bannann Nan." Released in his final days of office, it was a raunchy, suggestive attack on journalist Liliane Pierre-Paul. This was the Sweet Micky persona at its most vitriolic. To his fans, it was just "Micky being Micky." To human rights activists, it was a sitting president using his power to bully a woman.

This duality is the core of his legacy. You have the innovator who modernized Haitian music, and you have the provocateur who frequently crossed the line of basic decency.

📖 Related: Cómo salvar a tu favorito: La verdad sobre la votación de La Casa de los Famosos Colombia

What We Can Learn from the Sweet Micky Era

Looking back, the "I Don't Care" period was the ultimate foreshadowing. It showed a man who understood the power of the "shock factor" long before social media made it a requirement for fame.

If you’re looking to explore this era deeper, here’s how to do it right:

- Listen to the 1994/1995 recordings: Don't just settle for the 2010 remasters. Find the raw, live recordings where you can hear the crowd's reaction. That’s where the energy is.

- Watch the documentary "Sweet Micky for President": Produced by Pras Michel of The Fugees, it gives a gritty, behind-the-scenes look at how the musician-persona translated into a political campaign. It’s eye-opening.

- Contextualize the lyrics: Use a Creole-to-English translation guide if you aren't a native speaker. The puns and double meanings (pwen) are where the real "meat" of the political commentary lives.

- Compare the "President" years to the "Micky" years: Notice how the suit changed the man, but never quite silenced the singer. Even as a world leader, he couldn't help but jump back on stage.

The legacy of Sweet Micky I Don't Care is a reminder that in politics and pop culture, sometimes the person who shouts the loudest—and cares the least—is the one who ends up holding the microphone at the end of the night. It’s a messy history, but it’s one that defines modern Haiti.

To truly grasp the impact, go back and find the original 8-minute version of the track. Put on some headphones. Listen to the way the bass interacts with the synth. You'll hear the sound of a country that was tired of being told what to do, led by a man who refused to follow the rules. That defiance is exactly why, decades later, we’re still talking about it.

Next Steps for Enthusiasts:

Start by listening to the full I Don't Care album (1994) to hear the transition from pure Konpa to political satire. Then, cross-reference the track "Mon Colonel" to see how Martelly played with military themes during the coup era. Understanding the specific political climate of 1994 is the only way to catch the "hidden" jabs in the lyrics.