If you walked into a Charlotte, North Carolina, classroom in 1968—nearly fifteen years after the Supreme Court supposedly ended segregation with Brown v. Board of Education—you’d have seen something confusing. You would have seen schools that were almost entirely Black and schools that were almost entirely white. It wasn’t just a coincidence. It was the result of decades of "neighborhood schooling" that basically kept the old system alive under a different name.

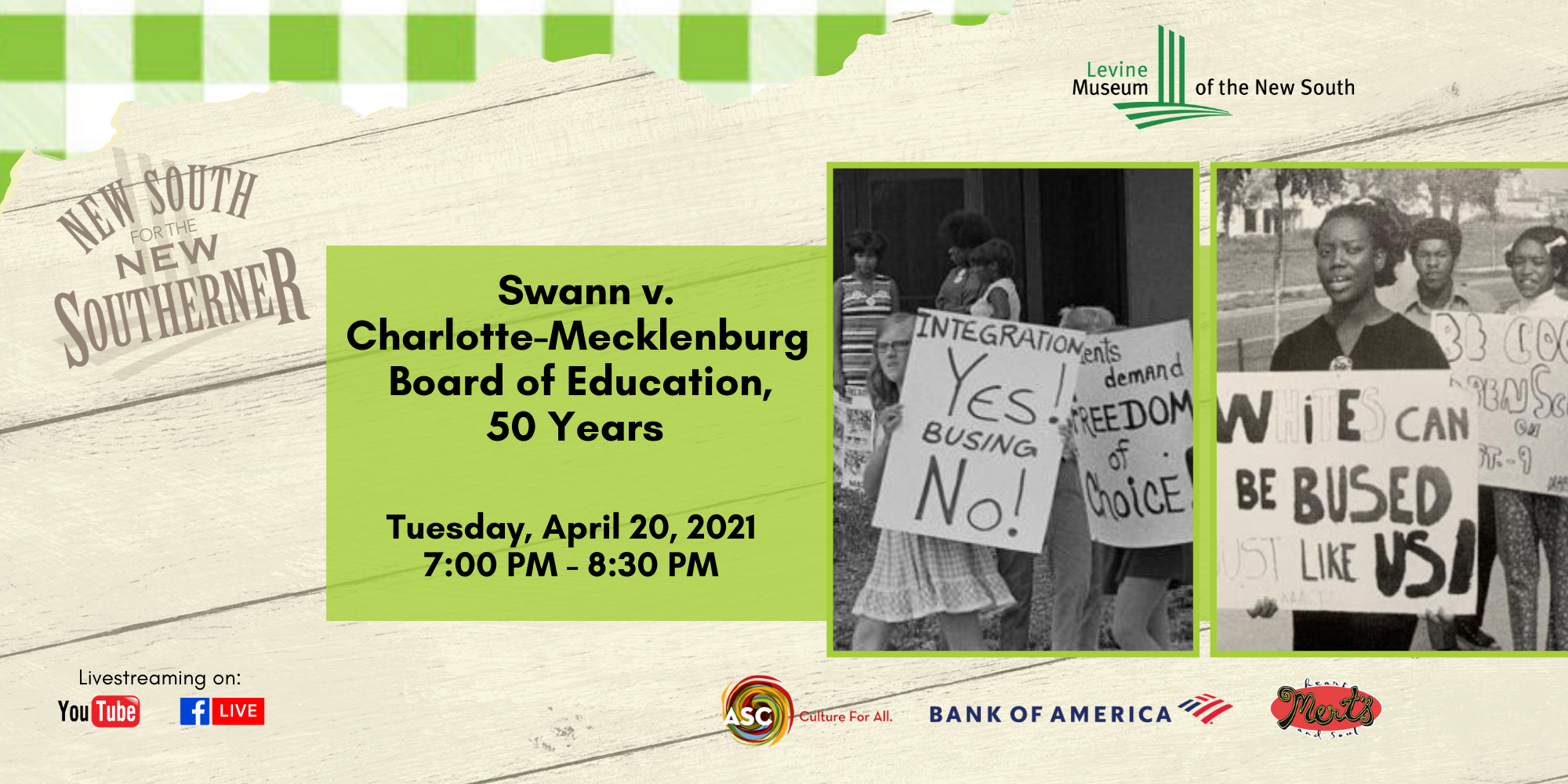

The legal battle that changed all of this, Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, wasn't just some dry court case. It was a local explosion that turned into a national blueprint. It was about whether "equal opportunity" was just a nice phrase or something the government actually had to force into existence through busing.

Honestly, the story starts with a six-year-old named James Swann. His parents, Vera and Darius Swann, just wanted him to go to the school down the street—Seversville Elementary. But Seversville was "integrated" only on paper. The district used "freedom of choice" plans, which sounds great in theory but in reality, almost no white students "chose" to go to Black schools, and Black families faced massive social and economic pressure not to transfer into white ones.

Why the Finger Plan Changed Everything

When the case landed on the desk of District Judge James B. McMillan, people expected him to side with the status quo. He was a local guy, a moderate, and had even spoken out against busing before. But as the evidence piled up—literally two and a half feet of it—McMillan changed his mind. He realized that the "neighborhood school" was a myth in a city where the government had spent years deciding which neighborhoods were Black and which were white.

He brought in an expert from Rhode Island named Dr. John Finger. The "Finger Plan" was radical. It didn't just tweak boundaries; it proposed busing thousands of kids across the city. Black kids from the inner city would head to the suburbs, and white kids from the suburbs would head into the city.

📖 Related: The Galveston Hurricane 1900 Orphanage Story Is More Tragic Than You Realized

The backlash was instant and violent. Julius Chambers, the lead attorney for the Swann family, had his home, car, and law office bombed. People were angry. They felt their children were being used as "social experiments."

What the Supreme Court Actually Decided

The case eventually hit the Supreme Court in 1971. Chief Justice Warren Burger wrote the unanimous opinion, and it was a powerhouse. Basically, the Court said that if a school district had been segregated by law in the past, they couldn't just say "oops, our bad" and leave things as they were. They had an "affirmative duty" to fix it.

Here are the big takeaways from the 1971 ruling:

- Busing is a "remedial tool." The Court ruled that it was perfectly constitutional to use buses to achieve racial balance.

- Mathematical Ratios. While they didn't require every school to be a perfect 70/30 split, they said using those ratios as a "starting point" was okay.

- Gerrymandering for Good. For once, the Court allowed redrawing district lines specifically to promote integration rather than prevent it.

It’s important to realize that the Court distinguished between de jure (segregation by law) and de facto (segregation by choice or housing patterns). Because Charlotte had a history of legal segregation, the courts had the power to step in with heavy-handed fixes.

👉 See also: Why the Air France Crash Toronto Miracle Still Changes How We Fly

The "Charlotte Way" and the Rise of Resegregation

For about 25 years, Charlotte-Mecklenburg became a national model. It was known as "the city that made desegregation work." People actually started taking pride in it. In 1974, students from West Charlotte High even invited kids from Boston—where busing riots were getting ugly—to come down and see how it was done.

But things didn't stay that way. By the late 1990s, a new group of parents sued the district, arguing that the "vestiges of segregation" were gone and that it was now white students being discriminated against by the busing quotas.

In 1999, Judge Robert Potter (ironically, a judge appointed by Reagan) ruled that the district had achieved "unitary status." This basically meant the court's job was done. The busing stopped. The result? By 2002, Charlotte schools resegregated almost overnight.

What We Learned (The Hard Way)

Looking back, the legacy of Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education is complicated. On one hand, it proved that you can integrate a city if the government is willing to use its power. On the other hand, it showed how fragile that progress is once the legal pressure is removed.

✨ Don't miss: Robert Hanssen: What Most People Get Wrong About the FBI's Most Damaging Spy

Recent studies, like the one from the NBER, show that when the busing ended in 2002, racial inequality in Charlotte widened. Test scores for minority students dropped, and crime rates for minority males in the newly segregated schools went up. It turns out that "neighborhood schools" in a segregated city usually just lead to segregated education.

How to Understand the Legacy Today

If you're trying to figure out where we stand now, look at your local school board's "assignment policy." Most cities have moved toward "school choice" or "magnet programs." These are basically the descendants of the Swann era—attempts to get diversity without the "forced" feeling of the 1970s busing plans.

Next Steps for Research:

- Check your local school's "Unitary Status." Many districts across the South are still under court supervision, or only recently "graduated" from it. You can usually find this in the district's legal archives or via the Civil Rights Project at UCLA.

- Look at the "Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools (CMS) 2002 Re-zoning." Comparing map data from 1990 to 2010 in Charlotte is a masterclass in how quickly housing patterns can dictate educational quality.

- Read the original Swann opinion. It's a surprisingly readable document that explains exactly why the "neighborhood school" isn't always a neutral concept.

The reality is that Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education didn't solve racism in schools. But it did prove that the law has the teeth to try, provided there's a judge brave enough to use them.