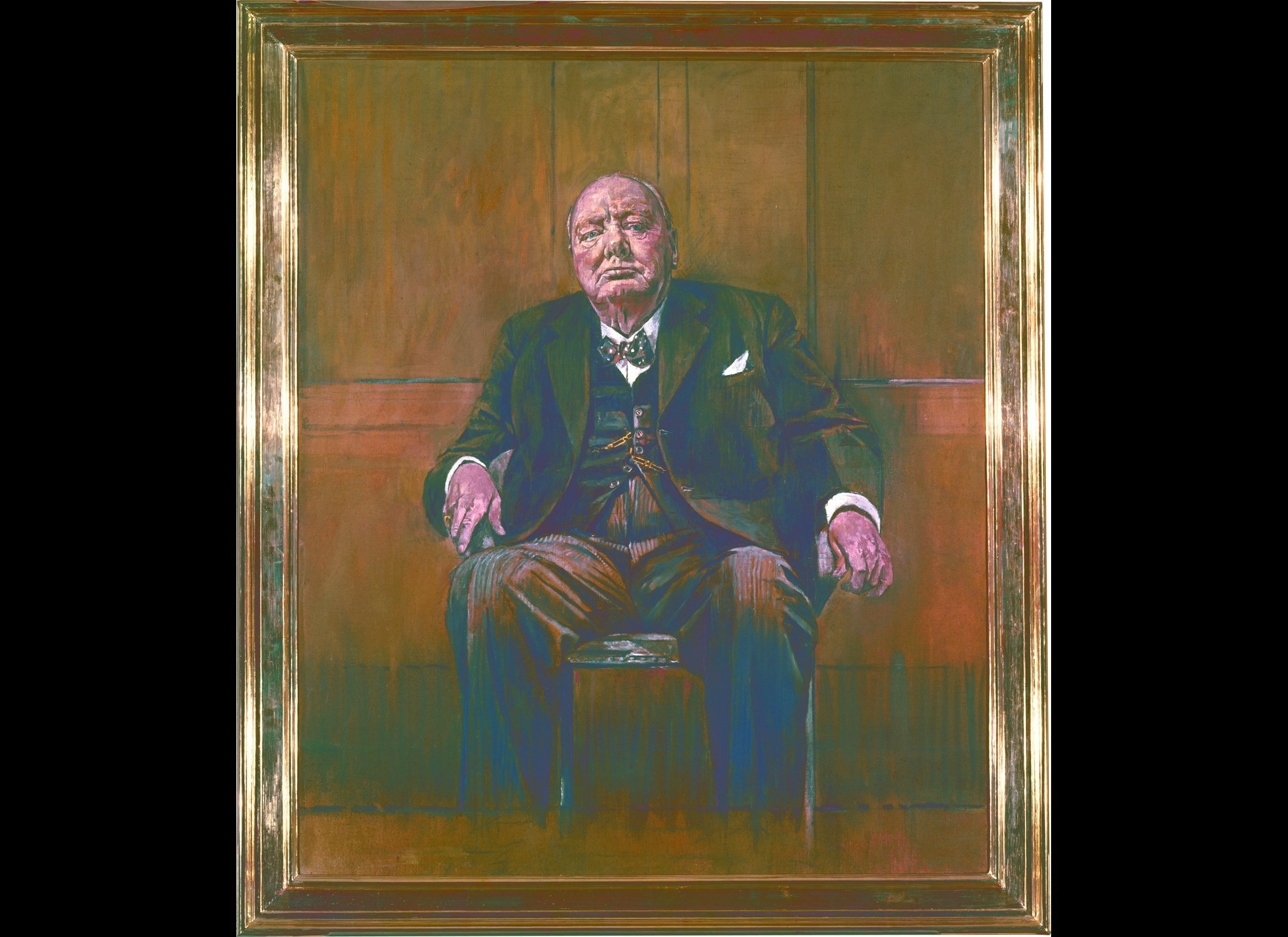

Imagine being the most powerful man in the world, surviving the Blitz, and outlasting Hitler, only to be defeated by a piece of canvas and some oil paint. That’s basically the story of Sutherlands portrait of Churchill. Most people know the drama from The Crown, where John Lithgow’s Winston stares in horror at a painting that makes him look like a "down-and-out drunk."

But the real history? It’s even messier.

In 1954, the Houses of Parliament wanted to give Winston Churchill a massive 80th birthday present. They chose Graham Sutherland, a modernist heavy-hitter, to capture the Great Man. It was a clash of titans from the start. Churchill wanted to be a "cherub" or a "Bulldog" in his Knight of the Garter robes. Sutherland, however, was an artist who painted what he saw.

And what he saw was an 80-year-old man who had suffered multiple strokes.

Why Churchill Truly Hated the Portrait

Churchill didn't just dislike the painting; he felt physically attacked by it. When he first saw a photo of the finished work, he described it as "filthy" and "malignant." Honestly, he thought there was a conspiracy within the Tory party to use the painting to force him into retirement. He told his doctor, Lord Moran, that the portrait made him look like he’d been "picked out of the gutter in the Strand."

The painting was supposed to be an "obituary in paint," according to historian Simon Schama.

✨ Don't miss: Am I Gay Buzzfeed Quizzes and the Quest for Identity Online

It was raw.

It was honest.

It was exactly what Churchill didn't want.

He famously joked during the unveiling at Westminster Hall that it was a "remarkable example of modern art," which was basically the 1950s version of saying "I hate this with every fiber of my being." The audience laughed, but Sutherland was humiliated.

The Secret Burning at Chartwell

For decades, nobody knew where the painting went. It just... vanished. People assumed it was rotting in a cellar at Chartwell, Churchill’s country home. It wasn’t until years later that the truth came out.

🔗 Read more: Easy recipes dinner for two: Why you are probably overcomplicating date night

Clementine Churchill, Winston’s wife, couldn't stand seeing how much the portrait distressed him. She had already destroyed other sketches of him she didn't like—she was protective like that. Around 1955 or 1956, she decided the Sutherland portrait had to go.

She didn't do it herself, though.

She asked Grace Hamblin, Churchill's private secretary, to handle it. Hamblin got her brother, a gardener, to help. They loaded the massive, heavy canvas into a van in the middle of the night. They drove it to a private garden miles away, built a huge bonfire, and threw the masterpiece into the flames.

Sutherland later called it an "act of vandalism." You've gotta feel for the guy; he spent months on it, thinking he was capturing the "real" Winston. Instead, he created the most famous pile of ash in art history.

The Mystery of the Surviving Studies

While the final Sutherlands portrait of Churchill is gone forever, the artist's preparatory work survived. Sutherland was meticulous. He didn't just paint the final piece; he did dozens of sketches and oil studies.

💡 You might also like: How is gum made? The sticky truth about what you are actually chewing

Recently, one of these studies—an intimate, side-profile view of Churchill—emerged from a private collection and was exhibited at Blenheim Palace before being auctioned for hundreds of thousands of pounds. These studies show a different side of the process. They aren't as "brutal" as the final version was reported to be. They show a pensive, vulnerable man.

It makes you wonder: if Sutherland had just gone with one of the softer sketches, would the painting still be hanging in Parliament today?

Key Facts About the Lost Masterpiece

- Commissioned by: Both Houses of Parliament for Churchill's 80th birthday.

- The Price: 1,000 guineas (a small fortune at the time).

- The Medium: Oil on canvas.

- The Fate: Incinerated on a bonfire in a backyard in Kent.

- The Recreation: In 1981, artist Albrecht von Leyden used Sutherland’s notes and photos to recreate the portrait. This version now hangs at the Carlton Club in London.

Insights for History Buffs

If you’re looking to understand the legacy of this painting, don't just rely on the TV version. The real tension was between two different philosophies of truth. Churchill believed art should be aspirational—it should show the hero the world needed. Sutherland believed art should be a mirror—it should show the man as he actually existed in time.

Next steps for your research:

- Visit the Carlton Club: If you're in London, you can see the von Leyden recreation to get a sense of the scale and "force" of the original.

- Check out the National Portrait Gallery: They hold several of the original preparatory sketches that escaped the fire.

- Read "Clementine Churchill" by Sonia Purnell: This biography gives the most detailed account of how the destruction was organized and why Clementine felt it was an act of love for her husband.

The destruction of the portrait remains a warning to artists everywhere: never underestimate a sitter's vanity, especially if that sitter is the man who won World War II.