You’re standing on a platform, looking down. Except there is no platform. There is no ground. If you tried to "land" on Saturn, you’d just keep falling. And falling. Honestly, the biggest misconception about the sixth planet is that it has a surface at all.

When we talk about the surface of Saturn, we’re usually talking about a mathematical convenience—a specific layer in the atmosphere where the pressure equals what you feel at sea level on Earth. But to your eyes? It’s just an endless, terrifying descent into a golden fog that eventually turns into a hot, liquid nightmare.

The "Surface" That Isn't There

If you could hover at that 1-bar pressure level—the "surface"—you’d see a sky that looks nothing like the deep blue of home. Because Saturn is mostly hydrogen and helium, the light scatters differently. It’s a hazy, pale gold or butterscotch color. Everything feels muted. You’ve got these massive ammonia ice clouds whipping past you at 1,100 miles per hour. That’s faster than a fighter jet.

The clouds aren't just one big mass. They’re layered like a cosmic lasagna. At the very top, you have ammonia ice. Below that, it’s ammonium hydrosulfide. Keep going, and you hit water ice. It sounds pretty, but the chemistry is brutal. The "air" is a cocktail of hydrogen, helium, methane, and traces of phosphine that would kill a human in seconds.

Gravity and the Float Factor

Here is a weird bit of physics: despite being 95 times more massive than Earth, Saturn is incredibly light for its size. It’s the only planet in the solar system less dense than water. If you found a bathtub big enough, Saturn would literally float.

Because of this low density, if you were "standing" at the cloud tops, the gravity pulling on you would only be about 91% of what you feel right now. If you weigh 150 pounds on Earth, you’d weigh about 136 pounds on Saturn. You’d feel a bit lighter, even as the winds tried to tear you apart.

Descending Into the Dark

As you fall deeper, things get dark fast. Sunlight can’t penetrate the thousands of miles of thick gas. Within a few hundred miles, you’d be in total pitch-blackness, illuminated only by the most violent lightning storms in the solar system.

The Cassini spacecraft, which spent 13 years orbiting the planet, captured "Great White Spots"—storms so massive they wrap around the entire planet. These aren't like Earth hurricanes. They are deep-rooted convective events that churn up material from hundreds of miles down.

✨ Don't miss: Cómo reiniciar un computador: Lo que nadie te dice sobre el botón de encendido

When the Gas Turns Liquid

This is where it gets really trippy. On Earth, we have a clear line between the air and the ocean. On Saturn, there is no "splash."

As the pressure increases, the hydrogen gas gets squeezed so hard it becomes a supercritical fluid. It’s not quite a gas, and it’s not quite a liquid. It’s both. You would slowly transition from falling through thick fog to swimming through a hot, dense soup. Eventually, thousands of miles down, the pressure becomes so high—millions of times Earth's atmospheric pressure—that the hydrogen turns into liquid metallic hydrogen.

The View from the North Pole

If you weren't falling into the abyss and instead visited the North Pole, you’d see the most famous geometric oddity in space: the Hexagon.

It’s a six-sided jet stream about 20,000 miles wide. You could fit nearly four Earths inside it. Why is it a hexagon? Scientists like Dr. Andrew Ingersoll and the Cassini team have spent years modeling it, and it basically comes down to fluid dynamics and the way the planet's rotation interacts with the wind. At the very center of this hexagon is a massive, permanent hurricane with an eye 50 times larger than an average Earth hurricane.

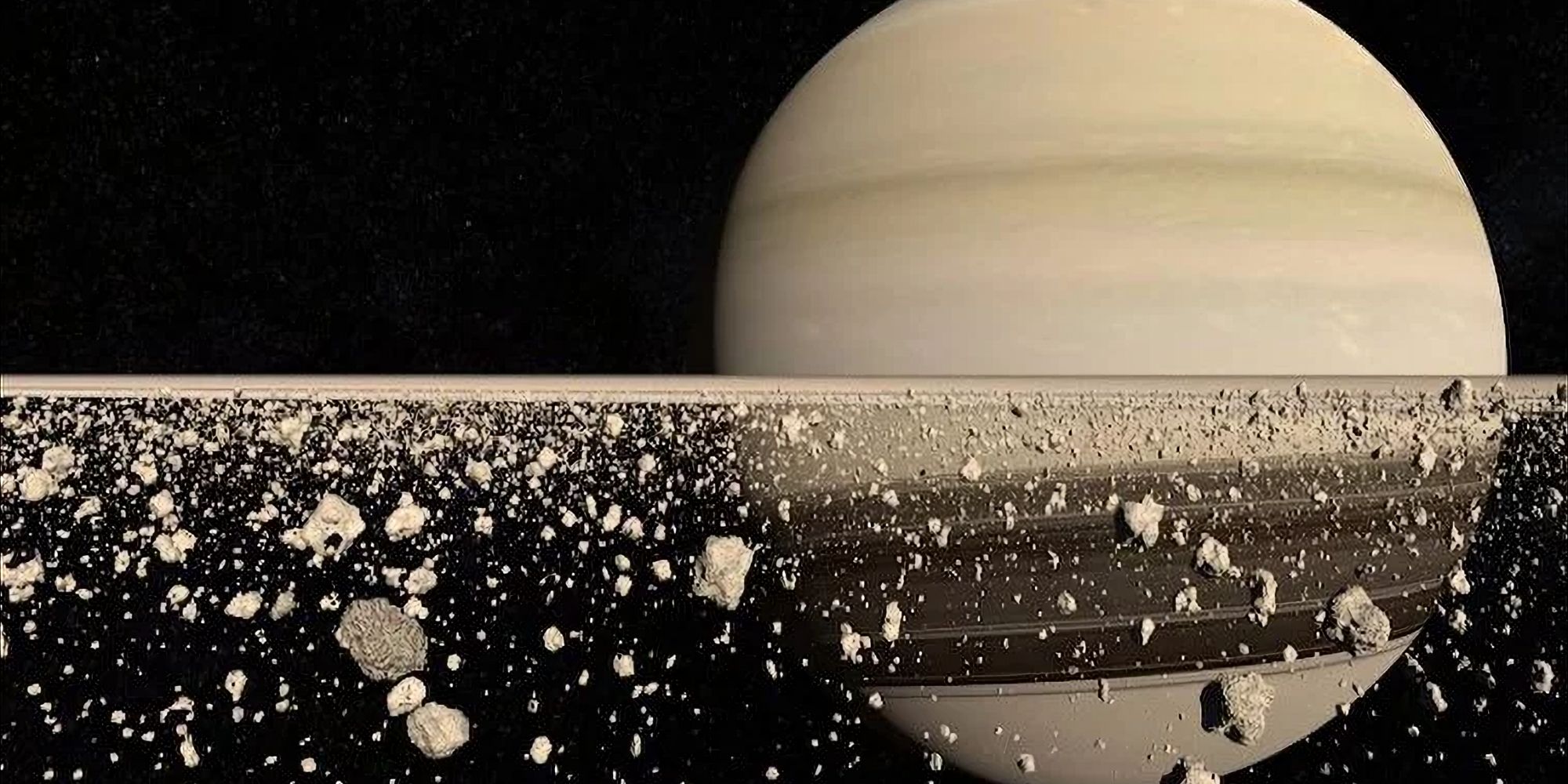

The Rings from the Cloud Tops

If you were in the upper atmosphere during a clear patch, the view would be life-changing. Saturn’s rings wouldn't look like the flat disks we see in telescopes. They would appear as a massive, shimmering arc stretching from horizon to horizon.

Because the rings are mostly water ice—ranging from the size of a grain of sand to a house—they catch the sunlight brilliantly. Depending on your latitude, they might look like a thin sliver or a broad, white highway across the sky.

What This Means for Future Exploration

We can’t land on Saturn. We know that now. The "surface" is a death trap of pressure and heat. However, that hasn't stopped us from planning ways to see it up close.

- Atmospheric Probes: NASA is looking at missions similar to the Galileo probe that dived into Jupiter. These would be "suicide" missions designed to beam back data for a few minutes before being crushed.

- The Moons are the Key: Since we can’t touch Saturn, we look at its moons. The Dragonfly mission, set to launch in 2027, is heading to Titan. Titan actually has a solid surface, methane lakes, and a thick atmosphere. It’s the closest we’ll get to standing in the Saturnian system.

- The Rings as a Lab: Scientists are using the rings as a giant "seismometer" to measure the vibrations of the planet's interior. This is how we’ve recently discovered that Saturn’s core is likely "fuzzy"—a mix of rock, ice, and metallic fluids rather than a solid ball of iron.

Actionable Insight: If you want to "see" the surface for yourself, don't look at artist renders. Go to the NASA Cassini Raw Image Archive. You can see the actual, unedited black-and-white photos of the cloud bands and storms. It looks less like a planet and more like a swirling, marbleized painting. It's a reminder that space doesn't have to be solid to be breathtaking.