Honestly, the Nintendo DS was a weird time for Sega. We were right in the middle of that mid-2000s fever dream where every developer felt legally obligated to force touch controls into games that didn't necessarily need them. Enter Super Monkey Ball Touch & Roll. Released in early 2006, it was supposed to be the handheld revolution for AiAi and the gang. It wasn't. Or maybe it was? It depends on who you ask and how much patience you have for a stylus.

Most people remember Super Monkey Ball for its surgical precision on the GameCube. You had that glorious octagonal gate on the analog stick that made precise cardinal directions a breeze. Then, Sega’s Sega Studio USA (the team formerly known as Sonic Team USA) decided to throw that out the window. They swapped the stick for a bottom-screen "trackball" metaphor. You swipe the stylus; the world tilts. It sounds intuitive on paper. In practice, it’s a bit like trying to perform brain surgery with a toothpick while riding a bus.

The Stylus Problem and the "D-Pad Secret"

The biggest hurdle for Super Monkey Ball Touch & Roll has always been the input lag. If you use the stylus—the way the box art practically demands you do—there is a microscopic but soul-crushing delay between your hand moving and the stage tilting. In a game where the later levels like "Dizzy System" or the master stages require millisecond adjustments, that lag is a death sentence.

But here is what most people get wrong: you don't actually have to use the touch screen.

📖 Related: Nintendo DS Sonic Classic Collection: Why This Messy Port is Still Worth Keeping

Sega tucked a traditional D-pad control scheme into the options. It’s better. Is it GameCube-level better? No. Digital inputs on a D-pad mean you lose the nuance of tilt degrees. You’re either tilting or you aren't. There’s no "half-tilt" for those narrow catwalks. This creates a fascinating, albeit frustrating, difficulty curve that isn't present in the console versions. You have to learn to "tap" the D-pad rhythmically to simulate a shallow angle. It’s a completely different meta-game.

Why the Level Design Feels Different

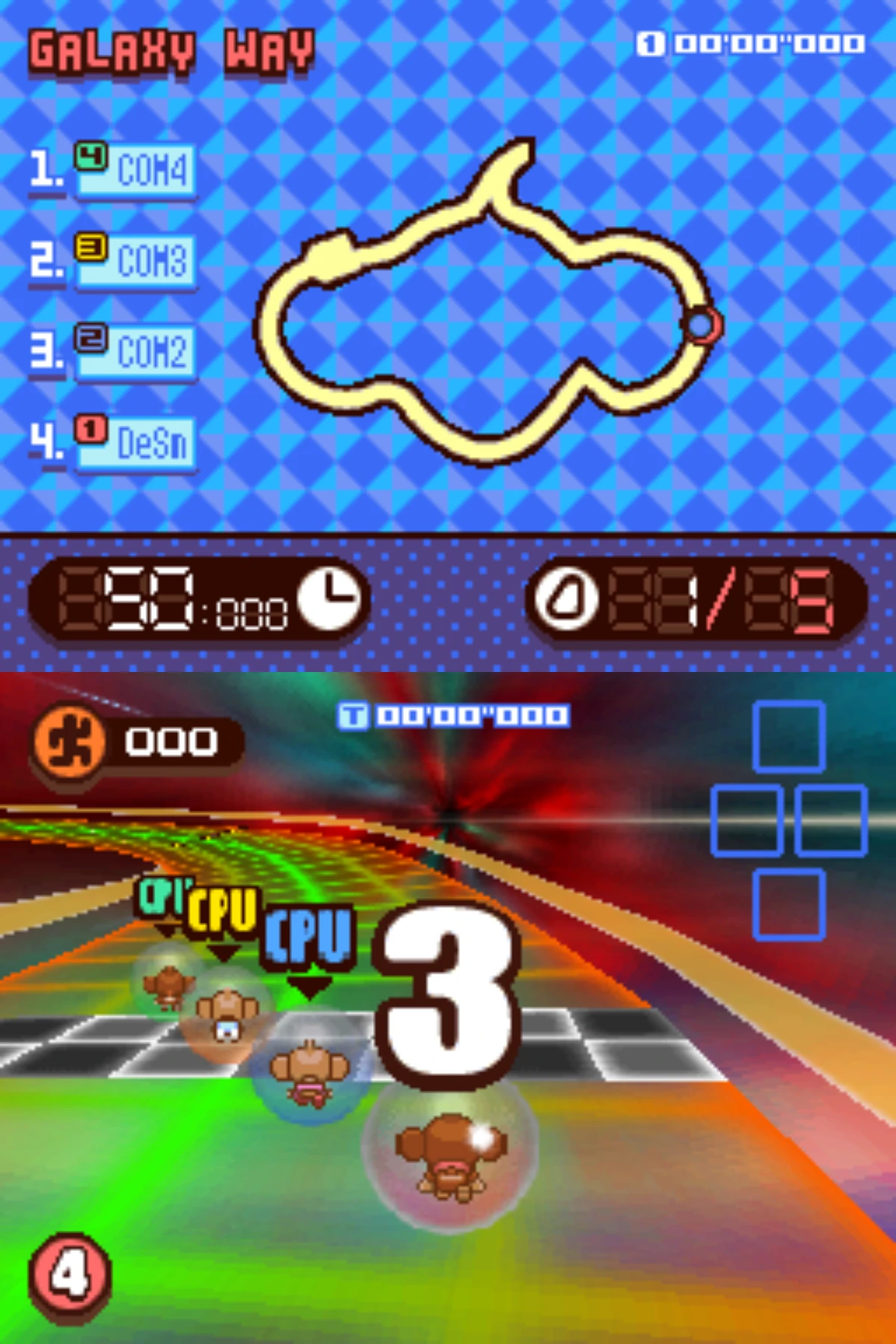

If you've played Super Monkey Ball 1 and 2, you’ll notice many of the 100 stages here feel familiar. That’s because many are "remixed" or directly inspired by the arcade originals. However, they had to be simplified. The DS hardware couldn't handle the complex geometry of the console versions without some serious optimization. This led to a "blockier" aesthetic.

- World 1-5: Generally breezy, meant to lure you into a false sense of security.

- The Mid-Game Slump: Around World 6, the physics engine starts to reveal its quirks. The collision detection on the edges of the goals feels "sticky" compared to the smooth transitions in Monkey Ball Deluxe.

The physics engine in Super Monkey Ball Touch & Roll is actually a bespoke creation for the DS. It doesn't use the same code as the Havok-powered console games. Consequently, the weight of the monkey ball feels slightly "floatier." When you hit a bouncer or a speed strip, the arc of your jump is more predictable but less organic. It’s less "rolling a ball in a box" and more "sliding a sprite on a grid."

Mini-Games: The Real Reason This Game Sold

Let’s be real. In 2006, we weren't just buying games for the main campaign. We wanted the "Party Games." This is where Super Monkey Ball Touch & Roll actually justifies its existence. While the main game struggles with the transition to handheld, the mini-games embrace the DS hardware with a chaotic energy that Sega usually reserves for WarioWare clones.

Monkey Fight is here. It’s iconic. Using the stylus to punch feels surprisingly tactile, even if the screen gets a bit scratched up in the process. Then there’s Monkey Bowling. This is arguably the best version of the mini-game outside of the original GameCube title. The flick-to-bowl mechanic on the touch screen is 1:1. It feels right. It feels natural. You can actually "hook" the ball by drawing a curve with the stylus. This was a "wow" moment in 2006 that still holds up if you dig your DS out of the drawer.

There are also some weird additions. Monkey Wars? It’s a first-person shooter. On a system with no analog sticks. It’s a mess, but it’s a fascinating mess. You navigate a maze and shoot other monkeys with balls. It’s clunky, the frame rate chugs, and the AI is either brain-dead or sniping you from across the map. Yet, it represents that experimental era of DS development where nobody knew what would stick, so they just threw everything at the wall.

The Audio Experience

One thing that never gets enough credit is the sound design. Sega’s sound teams are legendary. Even though the DS speakers are tinny, the soundtrack for Super Monkey Ball Touch & Roll is a masterclass in bubbly, energetic synth-pop. The "Ready... GO!" sample is crisp. The music doesn't just loop; it builds. It’s the kind of earworm that stays with you long after you’ve closed the clamshell in frustration because you fell off "Floor 48" for the twentieth time.

The Legacy of the "Touch" Experiment

Does Super Monkey Ball Touch & Roll matter in 2026? It’s a fair question. With Banana Mania and Banana Rumble available on modern consoles with actual analog sticks, the DS version seems like a relic. But it’s a pivotal relic.

📖 Related: Silent Hill Harry Mason: Why the Series’ Greatest Dad Still Matters in 2026

It was the first time Sega tried to decouple the franchise from the GameCube’s specific hardware strengths. It paved the way for the iPhone versions of Monkey Ball, which used the accelerometer. If Sega hadn't experimented with the DS touch screen, they might never have realized that the game works as a "gimmick" title.

The game also marks a specific point in Sega's history where they were aggressively trying to court the "Blue Ocean" audience—the non-gamers Nintendo found with Brain Age. The packaging was bright, the tutorials were hand-holdy, and the difficulty was—at least initially—toned down. It was a bridge between the hardcore arcade roots of the series and the more casual, party-focused direction it would take for the next decade.

Technical Limitations vs. Artistic Choice

The DS had a resolution of $256 \times 192$ per screen. Trying to render a 3D ball, a complex moving stage, and a skybox at a consistent 60 frames per second was a tall order. Super Monkey Ball Touch & Roll actually manages a decent frame rate, but at a cost. The draw distance is noticeably short. Fog is used heavily. If you look at the "Space" world, the background is mostly black to save on processing power.

Interestingly, the game uses a hybrid 2D/3D engine. The monkeys in the UI and some menu elements are high-quality 2D sprites, while the gameplay is fully 3D. This was a common trick to make DS games look more "premium" than they actually were. It’s a bit of smoke and mirrors that works until you zoom in too close.

What You Should Do If You Want to Play It Now

If you’re looking to revisit this game, or maybe play it for the first time, don't just grab a ROM and put it on an emulator. It feels terrible on a mouse. It feels even worse on a phone screen. This is a game built for a resistive touch screen—the kind you have to actually press into.

✨ Don't miss: Marvel Rivals Loki Skins: What Most Players Get Wrong About Lady Loki

- Get a DS Lite or a DSi. The original "Phat" DS screen is too dim for some of the later, darker levels. The DS Lite’s brighter screen makes a world of difference.

- Use a physical stylus. Don't use your finger. Your finger covers too much of the "trackball" on the bottom screen, making it impossible to see your fine-tuned movements.

- Try the D-Pad first. If you find the touch controls laggy, switch to the D-pad immediately. Don't try to "power through" the touch controls if they aren't clicking. The game becomes a much more traditional (and playable) experience with buttons.

- Focus on the Mini-Games. If the main 100 stages feel too derivative of the console versions, spend your time in Monkey Golf or Monkey Bowling. They are genuinely great handheld distractions.

Super Monkey Ball Touch & Roll isn't the best game in the series. It’s probably not even in the top five. But it’s an essential piece of Sega history. it represents a time when developers were genuinely excited—and terrified—of new ways to play. It’s a flawed, jittery, occasionally brilliant mess of a game.

For collectors, it's a cheap pick-up. You can usually find a loose cartridge for under $10. For that price, it’s worth it just to see how Sega tried to reinvent the wheel—or the ball—for a dual-screen world. It’s a reminder that even when a transition is rocky, there’s usually some charm to be found in the friction.

Instead of looking for a perfect port of the GameCube games, treat it as a weird experimental spin-off. It’s a product of its time, stuck between two eras of gaming, rolling along as best as it can with the tools it was given.