You've probably been there. It’s 4:45 PM on a Tuesday. Your boss wants a breakdown of Q3 sales for the "North" region, but only for "Widgets" and only if the transaction was over $500. You try to filter. You try a Pivot Table, but it looks messy. Then you remember that SUMIFS exists. You type it in, hit enter, and... $0. Or worse, a #VALUE! error that makes you want to throw your laptop out the window.

Honestly, the SUMIFS function is the workhorse of Excel and Google Sheets, but it's also remarkably picky. It's like that one friend who won't go to dinner unless the restaurant has gluten-free options, outdoor seating, and a specific brand of sparkling water. If you don't give it exactly what it wants, it just refuses to cooperate.

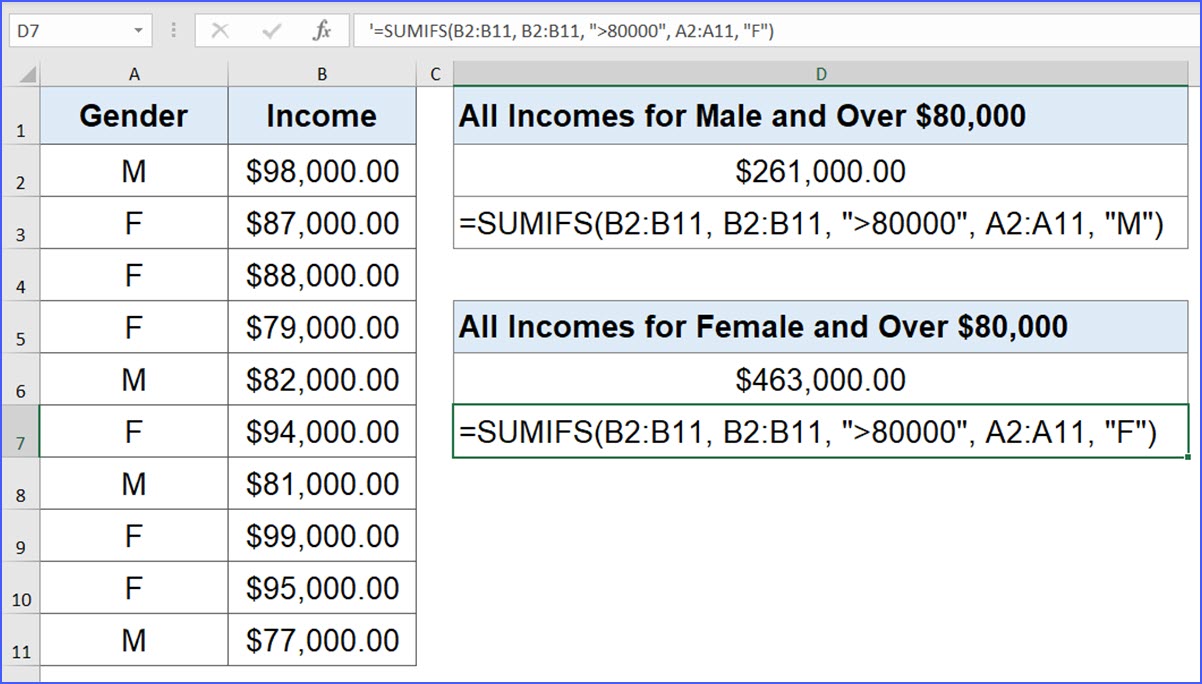

The beauty of this function is that it allows you to sum values based on multiple criteria. Unlike the old-school SUMIF (singular), which only lets you check one thing, SUMIFS lets you stack conditions until you get exactly the number you need. But there’s a logic to it that most people trip over because the syntax is actually reversed from the simpler version.

The Logic Behind the SUMIFS Formula

Let's look at the "math" without looking like a textbook. Most functions start with what you're looking for, but SUMIFS starts with the prize.

The very first thing you tell Excel is: "What column has the actual money (or units) I want to add up?" This is your sum_range. If you mess this up and put your criteria first, the formula will just stare back at you blankly. After you define the money column, you start pairing things up. Range, then Criteria. Range, then Criteria. It’s a buddy system.

$\text{SUMIFS}(\text{sum_range}, \text{criteria_range1}, \text{criteria1}, [\text{criteria_range2}, \text{criteria2}], \dots)$

Think of it as a nightclub bouncer. The sum_range is the dance floor. The criteria_ranges are the lines of people waiting outside. The criteria are the rules. "Are you on the list?" "Are you wearing a tie?" If someone passes every single check, they get onto the dance floor. If they fail even one, they're out.

Why Your Formula Returns Zero

This is the most common frustration. You know there is data there. You can see it with your own eyes. Yet, the formula insists the answer is zero.

Nine times out of ten, this is a data type mismatch. Excel is incredibly literal. If you are looking for the number "100" but your data is stored as text—perhaps it was exported from a buggy CRM—Excel sees them as two completely different things. It’s like trying to find a needle in a haystack, but the needle is actually a hologram.

Another huge culprit? Leading or trailing spaces. "North" is not the same as "North ". That tiny space at the end of the word, invisible to the naked eye, will break your SUMIFS every single time.

I’ve seen people spend hours rebuilding entire spreadsheets when all they needed was a TRIM function to clean up their data. If you're working with data exported from SAP or Oracle, do yourself a favor and run a quick check for "ghost spaces" before you start blaming your formula skills.

Dealing with Dates and Greater Than/Less Than

This is where things get genuinely weird. When you want to sum everything after January 1st, you have to wrap your operators in quotation marks.

It looks like this: ">1/1/2024".

Why? Because Excel treats the ">" as part of a text string that it evaluates against the range. If you want to point to a cell that contains a date, you have to use an ampersand to glue them together, like ">"&A1. It’s clunky. It feels like 1995. But it's the only way the engine understands what you're asking.

Real-World Examples That Actually Matter

Let’s stop talking in abstract terms. Imagine you're a project manager at a construction firm. You have a massive list of expenses.

You need to find the total cost of "Lumber" (Column B) for the "Oak Street Project" (Column C) where the cost (Column A) was greater than $1,000.

📖 Related: Azure Blob Storage: Why It’s Still the King of Unstructured Data

Your formula would look like this: =SUMIFS(A:A, B:B, "Lumber", C:C, "Oak Street Project", A:A, ">1000").

Notice how we used Column A twice? Once as the "prize" (the sum_range) and once as a filter. This is a pro move. You can filter by the same column you are summing. It’s perfectly legal and incredibly useful for finding high-value outliers in a sea of small transactions.

Wildcards: The Secret Weapon

Sometimes you don't know the exact name of what you're looking for. Maybe you have "Lumber - Cedar" and "Lumber - Pine" and "Lumber - Oak."

If you just want all the lumber, you use the asterisk (*).

Searching for "Lumber*" tells Excel to find any cell that starts with "Lumber" and has literally anything else after it. It’s a lifesaver when your data entry team isn’t consistent with their naming conventions. Honestly, without wildcards, SUMIFS would be half as useful as it is.

The Secret Performance Killer

We need to talk about "Volatile" behavior and large datasets. While SUMIFS isn't technically a volatile function—meaning it doesn't recalculate every time you click a cell—it can still get sluggish.

🔗 Read more: Mac OS X Disk Speed Test: Why Your Mac Feels Slow and How to Actually Fix It

If you have a spreadsheet with 500,000 rows and you're using 50 different SUMIFS formulas that reference entire columns (like A:A), you’re going to feel the lag. Excel has to check every single one of those half-million rows for every single formula.

Microsoft’s own performance documentation suggests using Table references (like Table1[Amount]) instead of whole-column references. It’s cleaner, it’s faster, and it makes your formulas much easier to read when you come back to them six months later and have no idea what "Column BK" was supposed to be.

Moving Beyond Basic Text

You aren't limited to just "is it equal to X?"

You can use logic like "not equal to." In Excel-speak, that’s <>. If you want to sum everything except the "Internal" department, your criteria would be "<>Internal".

You can also use the question mark (?) as a wildcard for a single character. If you have part numbers like "Part-1" and "Part-A", and you want to catch any five-character string that starts with "Part-", the question mark is your best friend.

Common Mistakes Even Pros Make

- Wrong Range Sizes: This is a big one. Your sum_range and your criteria_range must be the exact same size. If one goes from row 1 to 100 and the other goes from row 1 to 101, you get a #VALUE! error. They have to be symmetrical.

- The "Double Quote" Trap: Putting quotes around a cell reference. If you write

"=B1", Excel looks for the literal text "B1" in your data. It won't look at the value inside cell B1. - Hidden Rows: By default, SUMIFS includes hidden rows. If you’ve filtered your data manually and expect the formula to only sum what’s visible, you’re going to be disappointed. You’d need the AGGREGATE or SUBTOTAL functions for that, which are a whole different beast.

Actionable Steps for Your Next Spreadsheet

If you're ready to master this, start small. Don't try to build a 10-criteria mega-formula on your first go.

First, audit your data. Use the "Remove Duplicates" tool on a copy of your data to see what your actual categories are. This prevents you from searching for "North" when the data actually says "N. Region."

Second, use cell references. Instead of typing "Lumber" into the formula, put the word "Lumber" in cell E1 and point your formula there. It makes your sheet dynamic. Want to see "Steel" costs instead? Just change one cell instead of editing five formulas.

Third, test with a small sample. Copy ten rows of data to a new sheet and make sure the formula works there. It's much easier to troubleshoot ten rows than ten thousand.

👉 See also: Is the Midea U Shaped AC Recall Actually Real? What Owners Need to Know

Lastly, remember that SUMIFS is an "AND" function. Every criteria must be met. If you need an "OR" function—meaning you want to sum if it's "Lumber" OR "Steel"—you actually have to add two SUMIFS together.

=SUMIFS(...) + SUMIFS(...)

It feels a bit like cheating, but it’s the most reliable way to handle "OR" logic without diving into the terrifying world of Array Formulas or SUMPRODUCT. Keep it simple. Your future self, who has to fix this spreadsheet in three months, will thank you.