You’ve seen the map in every classroom. It’s a familiar sight, but honestly, it’s a lie. Most sub saharan africa maps you’ve grown up looking at are fundamentally distorted because of a math problem from the 16th century. If you look at a standard Mercator projection, Africa looks roughly the same size as Greenland. In reality? You could fit the entire United States, China, India, and most of Europe inside Africa with room to spare. Greenland is about fourteen times smaller.

Maps aren't just paper and ink. They are power. When we talk about sub-Saharan Africa—a region containing 46 of the continent’s 54 countries—we’re dealing with a landmass so massive and diverse that a single "map" can’t actually capture it. Whether you are a traveler planning a route through the Serengeti or a researcher tracking urban expansion in Lagos, the map you choose determines what you see and, more importantly, what you miss.

The Mercator Problem and Why Size Matters

Most people don't realize that flattening a sphere onto a rectangular sheet of paper requires some creative stretching. Gerardus Mercator designed his map in 1569 for sailors. It kept straight lines for navigation, but it bloated the northern and southern poles. Because of this, the equatorial regions—where most of sub-Saharan Africa sits—look tiny.

This isn't just a "fun fact" for geographers. It affects how we perceive the world's importance. When a continent is shrunk down visually, its economic and geopolitical weight is often subconsciously dismissed. If you want a more accurate look at the actual landmass, you need to check out the Peters Projection or the AuthaGraph. These aren't as pretty for navigation, but they show the sheer, staggering scale of the Sahel, the Congo Basin, and the Kalahari.

Think about it this way: the distance from Dakar, Senegal, to Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, is roughly 3,800 miles. That is significantly longer than the distance from New York City to Los Angeles. Yet, on many sub saharan africa maps, it looks like a short hop. This leads to massive logistical errors for businesses and travelers who underestimate the "Great African Distance."

Beyond Political Borders: The Maps They Don't Show You

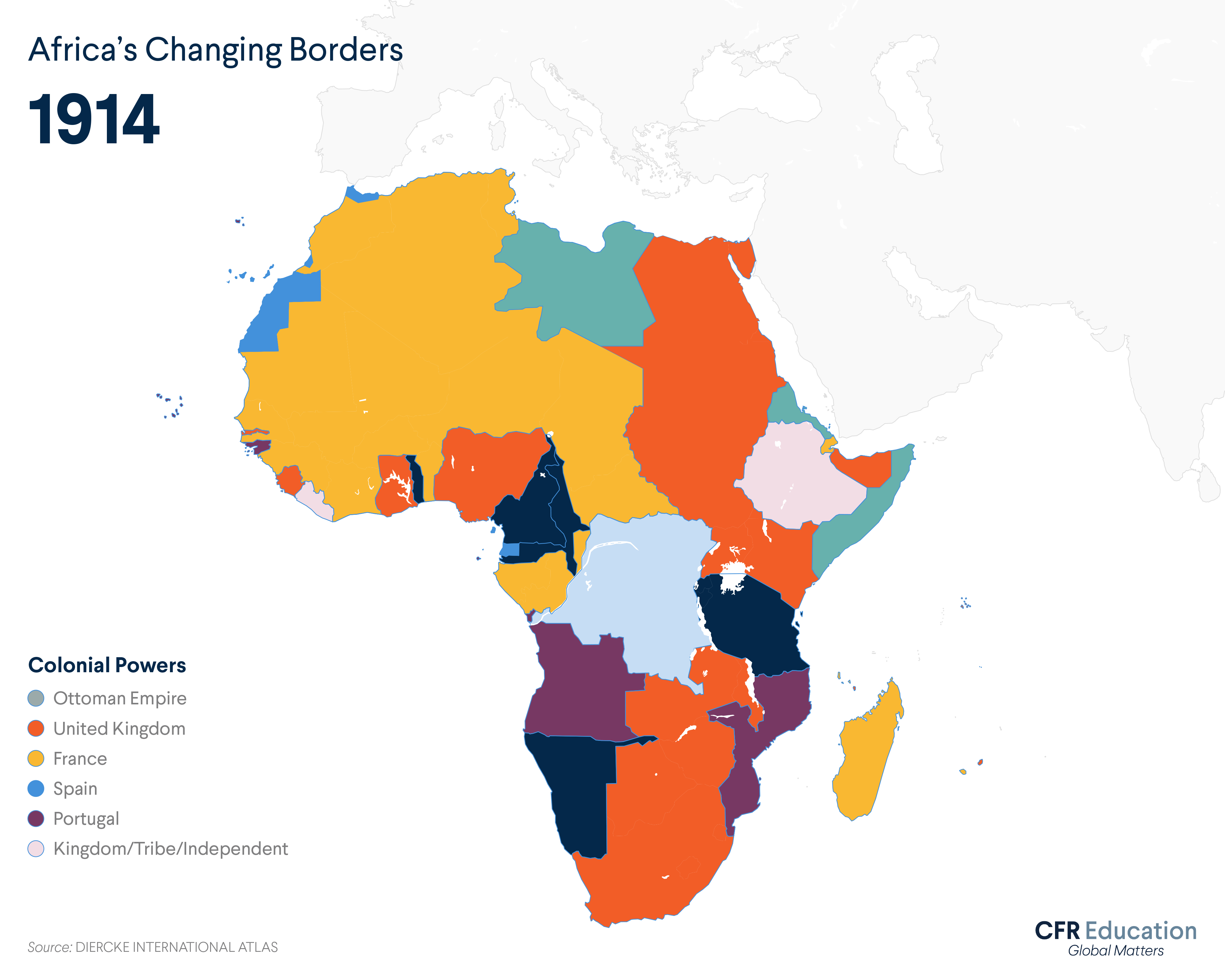

If you look at a standard political map, you see neat lines. These lines were mostly drawn during the Berlin Conference of 1884-1885 by European powers who had never even set foot in the interior. They ignored mountains, rivers, and, most crucially, people.

✨ Don't miss: Hotel Gigi San Diego: Why This New Gaslamp Spot Is Actually Different

To really understand the region, you have to look at ethnolinguistic maps.

George Murdock’s famous 1959 map of African tribal domains is a mess of overlapping colors and intricate shapes. It shows thousands of distinct groups. When you overlay this with a modern political map, you start to understand why certain regions face internal friction. A single national border might cut right through the heart of an ancient kingdom or force two groups with a history of conflict into the same administrative "box."

The Infrastructure Gap

There’s another way to map this place: light.

Satellite imagery of Africa at night is a stark contrast to Europe or East Asia. While the Nile River and the South African coast glow brightly, vast stretches of the interior remain dark. This isn't just about "development"—it’s about how energy is distributed. But look closer at a map of fiber optic cables. You'll see a massive web of connectivity hugging the coastline, with cables like 2Africa and Equiano literally wrapping around the continent to bring high-speed internet to hubs like Nairobi and Luanda.

Understanding the "Sub-Saharan" Label

We use the term "Sub-Saharan Africa" constantly. It basically refers to everything south of the Sahara Desert. But geologically and culturally, the transition isn't a hard line. It's a "Sahel"—a shore.

🔗 Read more: Wingate by Wyndham Columbia: What Most People Get Wrong

- The Sahel: This is the transition zone. It’s where the sand meets the savanna. Maps of this region are changing rapidly because of "The Great Green Wall" project, an ambitious plan to plant a belt of trees across the entire width of the continent to stop desertification.

- The Horn of Africa: This is the jagged bit on the east. It's geologically active. If you look at a tectonic map, the East African Rift is literally pulling the continent apart. Eventually, millions of years from now, a new ocean will form here.

- The Congo Basin: This is the green heart. It’s the second-largest tropical rainforest in the world. Many maps fail to show how vital this area is for global carbon sequestration, often prioritizing the Amazon instead.

Modern Mapping: The Digital Revolution

In places like Kibera in Nairobi or the sprawling districts of Lagos, traditional maps were useless for decades. They showed "blank spots" where hundreds of thousands of people lived.

Then came OpenStreetMap (OSM) and projects like "Missing Maps."

Volunteers use satellite imagery to trace buildings and paths, and locals on the ground add the names of shops, clinics, and water points using their phones. These are the most accurate sub saharan africa maps in existence today because they are "living" documents. They help NGOs deliver vaccines and allow entrepreneurs to set up delivery services in neighborhoods that officially "don't exist" on government records.

Climate and Topography: The High and the Low

Africa is often characterized as a low-lying tropical continent, but its topographic map says otherwise. Most of the southern and eastern parts of the continent are actually a massive plateau.

Johannesburg, South Africa, sits at an elevation of about 5,700 feet. That’s higher than Denver, the "Mile High City." This altitude affects everything from the climate to the way tea grows in the Kenyan highlands. When you look at a physical map, notice the "Great Escarpment" in South Africa—a massive cliff face that separates the high interior plateau from the coastal lowlands. It’s why many African rivers, like the Orange or the Zambezi, have massive waterfalls (like Victoria Falls) as they drop off the plateau toward the sea. These geographic features made the interior incredibly difficult for early explorers to reach by boat, which is why the "mapping" of the interior by outsiders happened so much later than in the Americas.

💡 You might also like: Finding Your Way: The Sky Harbor Airport Map Terminal 3 Breakdown

Actionable Insights for Using Africa Maps

If you are trying to actually use this information—whether for a school project, a business expansion, or a trip—stop using the first Google Image result you see.

1. Use the True Size Map: Go to websites like The True Size Of and drag African countries over Europe or North America. It will break your brain, but it’s the only way to internalize the scale.

2. Look at Vegetation Maps, Not Just Borders: If you’re planning travel, a political map won't tell you that crossing from Namibia into Angola means moving from a bone-dry desert into a lush tropical highland. Look for "Biomes" or "Ecoregions" maps.

3. Check the "Living Maps": For the most up-to-date info on roads and local infrastructure, use OpenStreetMap rather than just Google Maps. In many parts of rural Africa, the community-sourced data is much more granular and accurate.

4. Acknowledge the Nuance: "Sub-Saharan Africa" is a convenient shorthand, but it’s a category that lumps together the tech hubs of Rwanda, the oil fields of Nigeria, and the ancient rock-hewn churches of Ethiopia. No single map can tell the whole story.

The reality is that maps are always a choice. You choose what to emphasize and what to ignore. When it comes to sub-Saharan Africa, for too long, the maps ignored the people and the true scale of the land. But with new satellite tech and local mapping initiatives, we’re finally starting to see the continent for what it actually is: the massive, complex, and rapidly changing heart of the world.