Imagine looking out a window and seeing the entire world. It’s beautiful, right? But then you realize the door is locked from the outside, and the guy with the key just told you he’s going to be a few months late. That is basically the reality for astronauts who find themselves stuck in space. It’s not like a movie where there’s a dramatic countdown and then everyone dies in a fireball. Usually, it’s much more boring and way more stressful. It’s a lot of waiting, a lot of emails, and a lot of recycled sweat.

Space is hard. We say that all the time, but we don't really feel it until a valve fails or a software glitch turns a week-long mission into an eight-month marathon.

The Reality of Getting Stuck in Space

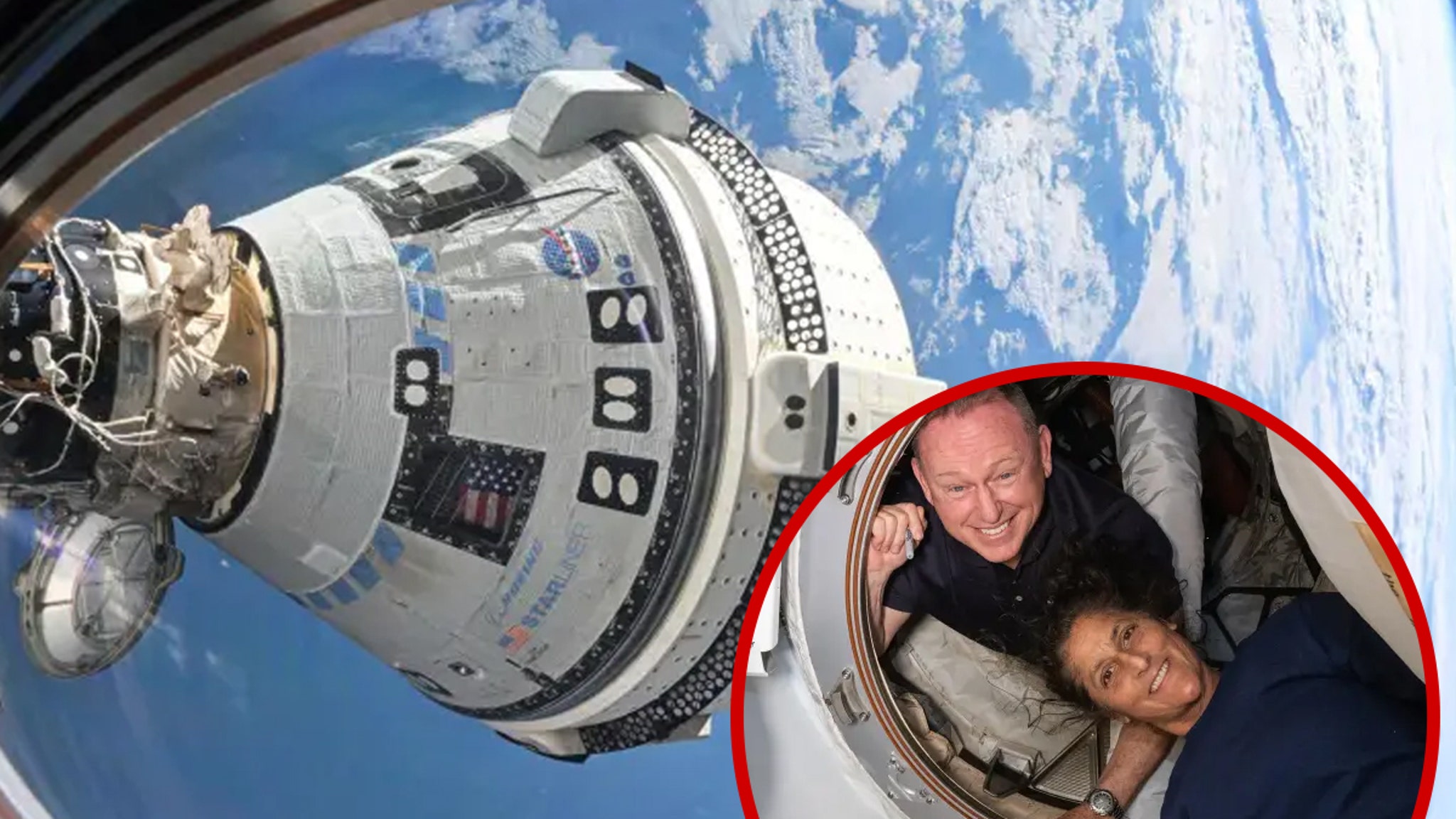

Most people think being stuck in space means drifting off into the void like Gravity. In the real world, it’s usually a logistical nightmare involving docking ports and propellant leaks. Take the recent Boeing Starliner situation. Butch Wilmore and Suni Williams went up for what was supposed to be an eight-day "taxi ride" to the International Space Station (ISS). They ended up watching their ship leave without them because NASA decided the thrusters were too risky for a crewed return.

They weren't "marooned" in the sense that they were floating helpless. They had a roof over their heads. But their life shifted instantly from a sprint to a cross-country trek.

When you’re up there longer than planned, the ISS starts to feel small. It’s about the size of a six-bedroom house, which sounds okay until you realize you’re sharing it with seven to nine other people and you can’t go for a walk. You’re breathing the same air. You’re eating the same dehydrated shrimp cocktail. Honestly, the psychological toll is probably worse than the technical risk. You miss birthdays. You miss the smell of rain. You miss gravity.

The Physics of Staying Too Long

The human body is built for Earth. When you stay stuck in space, your body starts to get confused. Without gravity pulling your fluids down, your face gets puffy—"moon face," they call it. Your bones start dumping calcium because they think they don't need to be strong anymore.

- Astronauts can lose 1% to 2% of bone mineral density every single month.

- Muscles atrophy, especially the ones in your legs and back that keep you upright.

- Radiation exposure increases, raising the long-term risk of cancer.

NASA and Roscosmos experts like Dr. Peggy Whitson, who holds the record for most days in space by an American, have talked extensively about the "bone loss" problem. Even with two hours of intense exercise a day using specialized machines like the ARED (Advanced Resistive Exercise Device), you can’t fully stop the decay. You’re basically fighting a losing battle against physics until you get your feet back on dirt.

Famous Cases of Cosmic Loitering

We have to talk about Sergei Krikalev. He is the ultimate "left behind" guy. In 1991, Krikalev went up to the Mir space station as a citizen of the Soviet Union. While he was up there, his country literally stopped existing. The USSR dissolved, the government changed, and the guys who were supposed to bring him home were dealing with a massive political collapse and a tanking economy.

He stayed for 311 days. He went up a Soviet and came down a Russian.

Then there’s Frank Rubio. He holds the record for the longest continuous spaceflight by an American—371 days. Why? Because a piece of space junk or a micrometeoroid hit his Soyuz MS-22 craft, causing a coolant leak. He didn't plan to break records. He just didn't have a safe seat home. He eventually said that if he had known he’d be up there for a year, he might have turned down the mission in the first place. That’s the kind of honesty you don't usually get in NASA press releases.

How We Actually Get Them Back

It’s all about the "rescue ship." When a vehicle is compromised, agencies have to play a high-stakes game of musical chairs.

- Assess the damage: Can the current ship fly autonomously? (In Starliner's case, yes).

- Reconfigure existing seats: Sometimes they move liners from one capsule to another.

- Launch a "blank": Sending up a SpaceX Crew Dragon or a Soyuz with empty seats specifically to act as a lifeboat.

The logistics are a nightmare. You have to account for different spacesuit brands. You can't just wear a Boeing suit in a SpaceX ship; the umbilical connections are different. It's like trying to charge an iPhone with a USB-C cable back in 2015. It just doesn't work.

The Engineering Failures That Leave People Stranded

Usually, it’s something small. A seal. A sensor. Helium leaks were the big story with the Starliner. Helium is used to pressurize the fuel lines so the thrusters can fire. If the helium leaks, you might not have enough pressure to steer the craft during the critical reentry burn.

Space is a vacuum, which means any tiny gap is an invitation for gas to escape. And then there’s the heat. Coming back to Earth involves hitting the atmosphere at 17,500 miles per hour. The friction creates temperatures around 3,000 degrees Fahrenheit. If your thrusters aren't perfect, your angle of entry is wrong. If your angle is wrong, you either skip off the atmosphere like a stone on a pond or you burn up.

NASA is notoriously risk-averse now, especially after the Challenger and Columbia disasters. If there’s even a 1% chance the thrusters might quit during the de-orbit burn, they’ll leave you stuck in space until a better ride shows up. It’s the right call, but it makes for a very long year for the crew.

The Impact on Future Mars Missions

If we get stuck in low Earth orbit, it’s a problem. If we get stuck on Mars, it’s a death sentence. There is no "rescue ship" for Mars that can get there in time. This is why SpaceX and NASA are obsessed with redundancy. You need multiple ways to generate oxygen, multiple ways to scrub CO2, and multiple ways to get off the rock.

👉 See also: Apple Vision Pro Return Policy: What I Learned Before Spending $3,500

Elon Musk has talked about the "Mars colonial fleet," but the reality is that the first few pioneers are going to be very much on their own. If their return vehicle fails, they aren't just waiting for a SpaceX taxi; they’re starting a new life as permanent Martians.

Actionable Steps for Space Enthusiasts and Researchers

If you’re following these missions and want to understand the real-time status of astronauts who are currently in orbit or potentially delayed, you shouldn't just rely on mainstream news snippets.

Track the ISS Live: Use the NASA Spot the Station tool. It tells you exactly when the station is overhead. Knowing those people are up there, sometimes longer than they planned, changes how you look at that moving dot of light.

Monitor Launch Manifests: Sites like SpaceFlight Now or the SpaceX official launch calendar show you the "bus schedule." If a mission is delayed on the ground, it almost always has a domino effect for the people currently stuck in space waiting for their relief crew.

Study Orbital Mechanics: If you really want to get into the weeds, look up "launch windows." You can't just leave space whenever you want. You have to wait for the station's orbit to align with your landing site on Earth. This is why even "healthy" missions sometimes get stuck for a few extra days due to bad weather in the Florida recovery zones.

Check the "Return to Flight" Stats: Look at the safety records of the Falcon 9 versus the Starship development. Understanding the "Probability of Loss of Crew" (LOC) metrics gives you a much better idea of why NASA makes the hard choice to keep people in orbit rather than risking a shaky landing.

Being stuck isn't just a failure of tech. It's a testament to how much we prioritize human life over the mission schedule. We've come a long way since the early days of the Space Race, where "getting there" was the only thing that mattered. Now, "getting back" is the part that defines a successful mission. Space is a lonely place to be, but at least these days, we have the technology to eventually bring everyone home.