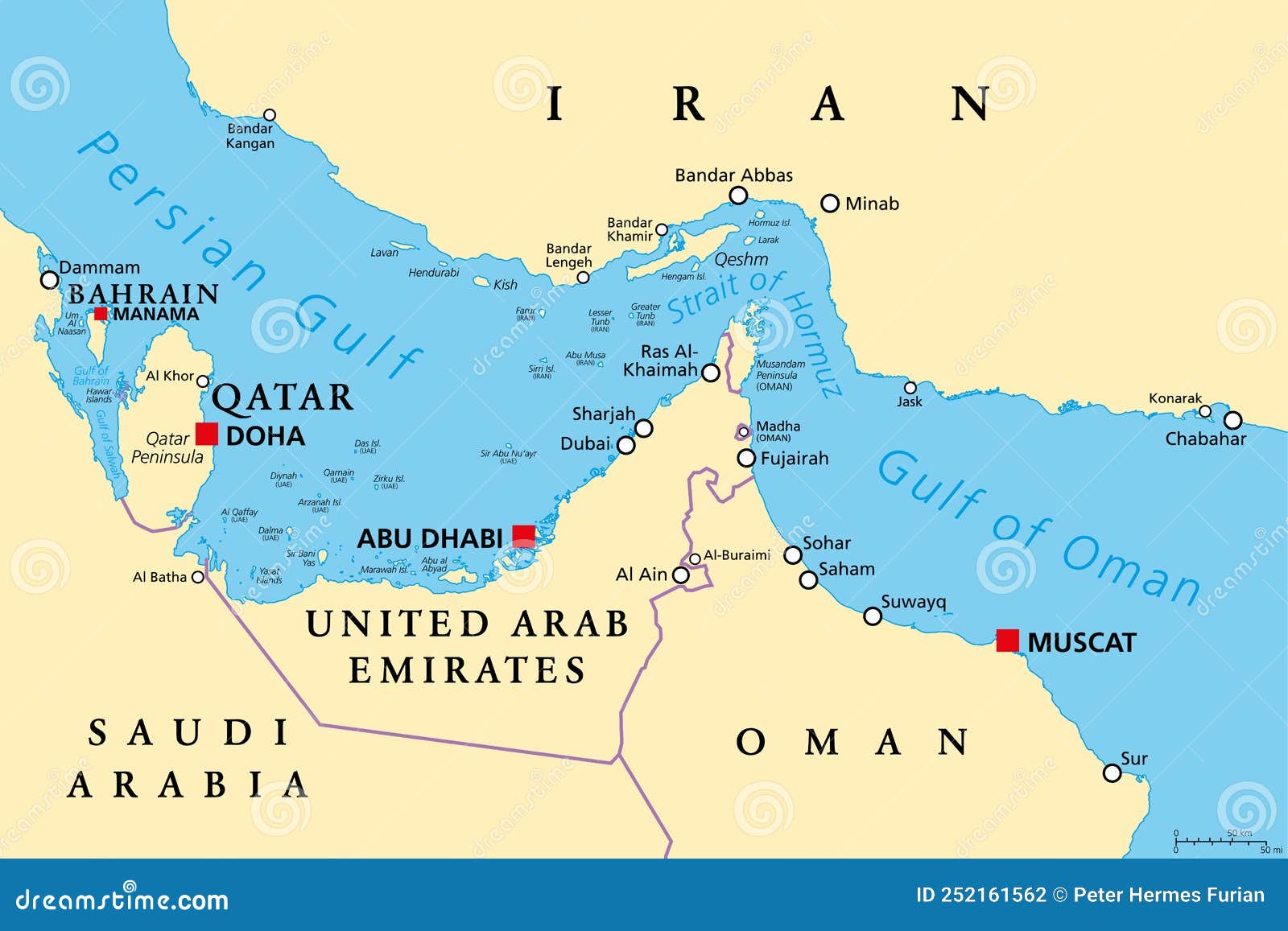

Look at the Strait of Hormuz on a map and you’ll see it looks like a pinched nerve between the Persian Gulf and the Gulf of Oman. It’s tiny. At its narrowest point, we are talking about only 21 miles of water separating the craggy coast of Oman from the southern cliffs of Iran. You could drive across that distance in twenty minutes if there were a bridge. But there isn't a bridge, and that small gap is arguably the most sensitive piece of real estate on the planet.

If you zoom in, you'll notice the shipping lanes are even tighter. Because of the shallow waters and rocky islands like Ormuz and Kish, the actual navigable channels for those massive "Very Large Crude Carriers" (VLCCs) are only about two miles wide in either direction. Think about that. The world's energy security is squeezed through a two-mile straw.

Why the Location is So Stressful for Markets

When you find the Strait of Hormuz on a map, you realize it’s the only way out for the oil-rich nations of the Middle East. Iraq, Kuwait, Qatar, and the United Arab Emirates are basically "landlocked" by water—they have no other maritime exit for their tankers. Saudi Arabia has the Red Sea, sure, but the bulk of their infrastructure still pushes eastward through this chokepoint.

Roughly 20 to 21 million barrels of oil flow through here every single day. That is about a fifth of the world's total consumption. If someone "plugs" the strait, the global economy doesn't just slow down; it hits a brick wall. This isn't just theory. We’ve seen the "Tanker War" of the 1980s and the more recent 2019 attacks on vessels like the Front Altair. Traders in London and New York keep a digital version of the Strait of Hormuz on a map pinned to their second monitors for a reason. One incident here and gas prices in a suburb in Ohio spike by fifty cents overnight.

The Geography of a Nightmare

Iran sits on the northern shore. They have the high ground, literally. The Musandam Peninsula, which belongs to Oman, sits on the south. Oman is generally the "quiet neighbor" that tries to keep the peace, but they are physically looking across at Iran's Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) navy, which operates out of bases like Bandar Abbas.

The IRGC doesn't use a traditional navy. They use "swarm" tactics. Hundreds of fast-attack boats, sea mines, and shore-based anti-ship missiles. Because the strait is so narrow, a big American carrier group—like the USS Abraham Lincoln—is actually at a disadvantage. It’s like trying to drive a semi-truck through a crowded alleyway while kids on bicycles throw water balloons at you. Except the balloons are C-802 missiles.

💡 You might also like: Russian Rupees to Euro: The Weird Reality of Stuck Billions

Strategic Islands You Probably Missed

If you’re staring at the Strait of Hormuz on a map, don't ignore the tiny dots in the water. Abu Musa and the Greater and Lesser Tunbs. These islands have been a source of friction between the UAE and Iran for decades. Iran seized them in 1971 just as the British were packing up and leaving.

Why do they matter? Because if you control those islands, you control the "gate" to the Persian Gulf. You can place radar, missiles, and surveillance gear right on the edge of the shipping lanes. It’s basically a set of unsinkable aircraft carriers parked in the middle of the world's most important highway.

How Much Oil Actually Moves?

Let's get into the weeds of the numbers because people often underestimate the scale.

- Crude Oil: Most of the 20 million barrels are headed to Asia. China, India, Japan, and South Korea are the biggest customers.

- LNG (Liquefied Natural Gas): Qatar sends almost all of its LNG through here. If you live in the UK or Japan and use gas to heat your home, there is a very high chance that energy passed through this 21-mile gap.

- The Alternatives: There are pipelines, like the Habshan–Fujairah line in the UAE or the East-West Pipeline in Saudi Arabia. But they can only handle a fraction of the volume. You can't replace the Strait. It's physically impossible with current infrastructure.

The "Invisible" Legal Battle

The legal status of these waters is a mess. Most of the navigable channel actually falls within the territorial waters of Iran and Oman. Under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), ships have the right of "transit passage." This means as long as a ship is just passing through and not being "threatening," the coastal states shouldn't stop it.

But here’s the kicker: Iran has signed UNCLOS but never actually ratified it. They argue that they only recognize "innocent passage," which is much more restrictive. They believe they have the right to board ships if they think there’s a security risk. This legal gray area is where all the tension lives. It’s why you see British or American warships escorting tankers. They aren't just there for show; they are there to assert a specific interpretation of international law.

The "Map" is Changing: New Ports and Bypasses

In recent years, countries have tried to "escape" the map. Look at the Port of Jask in Iran. It’s located outside the Strait in the Gulf of Oman. Iran built it specifically so they could export their own oil even if the Strait was closed during a war. It’s a bit ironic—the country most likely to close the Strait is also the one building a way to bypass it.

👉 See also: Can You Buy Ripple on Coinbase: What Most People Get Wrong

Similarly, the UAE has invested heavily in Fujairah. It’s become one of the world's largest "bunkering" (refueling) hubs. By moving operations to the eastern side of the Musandam Peninsula, they hope to mitigate the risk of a total blockade. But again, these are just band-aids. The sheer volume of global trade means the Strait of Hormuz on a map will remain the primary artery for the foreseeable future.

Why You Should Care (Beyond Gas Prices)

It's not just about oil. It’s about the "credibility of the commons." If a major power can just shut down a global waterway at will, the entire system of international trade falls apart. Insurance rates for ships (P&I clubs) would skyrocket. Food prices would rise because shipping containers carrying everything from grain to electronics would be rerouted or stuck.

We saw a tiny preview of this when the Ever Given got stuck in the Suez Canal. Now imagine that, but with the added threat of naval mines and drone strikes. That is the nightmare scenario that keeps Pentagon planners and Beijing strategists up at night.

Actionable Insights for the Global Citizen

Understanding the geography is the first step, but how do you actually use this information?

Monitor the "Crack Spread" and Brent Crude

If you see news about a "seizure" or "harassment" in the Strait, don't just look at the price of oil. Look at the shipping insurance premiums. When Lloyds of London designates the Persian Gulf as a "listed area," costs go up. This is usually a leading indicator of inflation in the energy sector.

Diversify Your Energy Exposure

If you are an investor, realize that "Energy" isn't a monolith. Companies with heavy exposure to West African or US Permian Basin production are "Hormuz-hedged." They actually benefit when the Strait gets dicey because the value of their "safe" oil goes up.

Watch the "Shadow Fleet"

There are hundreds of aging tankers with "dark" transponders moving Iranian and Russian oil through these waters. They don't follow the same safety standards as the big commercial fleets. The risk of a massive oil spill in the Strait of Hormuz is higher than it’s ever been. A major spill would be just as effective at closing the Strait as a minefield would, simply because no one could sail through the mess.

Keep an Eye on Oman

Everyone watches Iran, but Oman is the "canary in the coal mine." They are the facilitators. If Oman starts distancing itself from Western naval drills, it’s a sign that the regional temperature is reaching a boiling point.

The Strait of Hormuz on a map looks like a small, insignificant gap. But in reality, it is the center of the world. It is the place where geography, ancient rivalries, and modern hunger for energy collide. If you want to understand why the world looks the way it does, you have to start by looking at that tiny, 21-mile stretch of blue water. It’s the most important turn a ship can make.