Anthony Horowitz probably didn't realize he was changing the trajectory of middle-grade fiction when he sat down to write about a reluctant teenage spy. It was 2000. People were still mourning the end of the nineties. Computers were beige boxes. And then came Stormbreaker, the first installment of the Alex Rider series, which basically told every kid that they didn't have to wait until they were thirty to be James Bond. Honestly, looking back at it now, the book is a bit of a miracle. It’s lean. It's mean. It doesn't talk down to you.

Most "expert" reviews will tell you it’s just a riff on 007, but that’s a lazy take. While Bond usually has the backing of the British government and a martini waiting for him, Alex Rider is a fourteen-year-old kid who is essentially blackmailed into service. His uncle, Ian Rider, dies in what is supposedly a car accident. Alex finds out his uncle was actually a field agent for MI6. The grief is real, but the MI6 recruitment process is cold-blooded. They basically tell him: help us or we’ll deport your housekeeper and send you to a group home.

It’s dark stuff for a "kid's book." That’s exactly why it worked.

What Stormbreaker Got Right About Being a Teenager

The brilliance of the Alex Rider series book 1 isn't just the gadgets or the chase scenes. It’s the isolation. Horowitz nails the feeling of being a teenager who knows something the adults around him don't—or worse, realizing the adults are the ones causing the problems. Alan Blunt and Mrs. Jones aren't father and mother figures. They are handlers.

The plot kicks off when Alex is sent to Cornwall to investigate Herod Sayle. Sayle is a billionaire (classic trope, sure) who wants to donate a revolutionary "Stormbreaker" computer to every school in the UK. Sounds great, right? Wrong. It’s a Trojan horse. Literally.

I remember reading the scene where Alex finds the secret tunnel in the library for the first time. It felt visceral. Horowitz uses a lot of sensory details—the smell of damp earth, the chill of the air—to ground the high-stakes nonsense in a reality that feels tangible. It’s not just a story about a spy; it’s a story about a kid trying to survive a situation he’s totally unqualified for, even if he did spend his childhood being subconsciously trained in karate and languages by his dead uncle.

The Gadgets Aren't Magic

One thing people always forget about this first book is how grounded the tech was. In 2000, a Game Boy Color was the peak of handheld technology.

👉 See also: Diego Klattenhoff Movies and TV Shows: Why He’s the Best Actor You Keep Forgetting You Know

- Smithers gives Alex a Game Boy that acts as a smoke bomb, a bug finder, and a high-frequency transmitter.

- There’s the Zit-Clean cream that is actually an acid strong enough to eat through metal.

- Don’t forget the Nintendo-style cartridges that serve as different tools.

It’s tactile. It feels like something a kid in the year 2000 would actually have in his pocket. If you wrote this today, it would all be on an iPhone 15, and honestly, that would be way less cool. There's something inherently satisfying about a physical cartridge clicking into a device to save the day.

The Brutality of the Antagonist

Herod Sayle is a weird guy. He’s short, he’s angry, and he’s obsessed with his childhood trauma. He was bullied at school—specifically by the future Prime Minister—and his entire plan for mass murder is basically a "take that" to the British establishment. It’s petty. It’s human.

Most people focus on the jellyfish.

The Portuguese Man o' War in the giant tank in Sayle’s office is one of the most iconic images in the Alex Rider series book 1. It’s beautiful but deadly, a perfect metaphor for the danger Alex is in. When Sayle finally tries to kill Alex with it, the tension is genuinely high. Horowitz doesn't pull punches. Alex gets beaten up. He gets shot at. He almost drowns.

It’s worth noting that the book faced some criticism back in the day for its "violence." But kids aren't stupid. They know the world can be dangerous. Reading about a character who faces that danger and actually feels the pain of it is much more rewarding than a hero who walks away without a scratch.

The MI6 Dynamic

Let’s talk about Alan Blunt for a second. He’s the head of Special Operations. He’s described as looking like a gray, unremarkable accountant. That is terrifying.

In a world of colorful villains, the most dangerous people are often the ones in suits behind desks. Blunt’s willingness to put a child in the line of fire makes him just as morally ambiguous as the people Alex is fighting. This moral gray area is what separates this series from things like The Hardy Boys or Nancy Drew. There is no clear "good guy" organization. There is only the mission.

Why It Still Works in 2026

You might think a book about desktop computers from twenty-five years ago would be a relic. It’s not. The pacing is relentless. Horowitz writes in a way that mimics a movie script—short chapters, heavy on action, quick cuts between scenes.

✨ Don't miss: Did Mac Miller Like Donald Trump? What Really Happened Between the Rapper and the President

The central theme—a young person being forced to clean up the mess made by older generations—is actually more relevant now than it was in 2000. Whether it’s climate change, economic instability, or digital privacy, Gen Z and Gen Alpha feel that weight. Alex Rider is the patron saint of "I shouldn't have to deal with this, but I'm the only one who can."

Also, the prose is just fun.

Take the opening line: "When the doorbell rings at three in the morning, it's never good news."

That’s a hook. No fluff. Just immediate stakes.

The Movie and the TV Series

We have to mention the 2006 movie. Or maybe we shouldn't. It was... a choice. It tried too hard to be Spy Kids and lost the grit that made the book work. Thankfully, the more recent TV adaptation on Freevee/Amazon reclaimed that darker tone. If you're coming to the books after watching the show, you’ll find that the first book is much shorter than you expect, but every page earns its keep.

Technical Craft: How Horowitz Builds Suspense

Horowitz is a master of the "ticking clock." Throughout the second half of the book, we are constantly reminded that the Stormbreaker computers are about to be switched on.

The climax involves Alex literally jumping out of a plane to reach the Science Museum in London. It’s ridiculous. It’s over the top. But because the previous 150 pages built up the stakes so effectively, you totally buy it.

He also uses "The Reveal" perfectly.

When Alex discovers the truth about the Stormbreaker—the smallpox virus hidden inside—the shift from a tech-thriller to a biological horror story is jarring in the best way. It raises the stakes from "a kid is in trouble" to "thousands of children are going to die."

Common Misconceptions About the Series

A lot of people think the Alex Rider books are just for boys. Honestly? That’s nonsense. The themes of autonomy, resisting authority, and solving complex puzzles under pressure are universal.

Another misconception is that you can skip the first book if you've seen the movie. Please don't. The internal monologue of Alex—his resentment toward his uncle for "training" him without his consent—is much more nuanced in the text. You see him mourning Ian Rider while simultaneously being furious at him. That’s a complex emotion for a middle-grade novel to tackle.

🔗 Read more: Despicable Me 2 Edith: Why the Middle Child is Secretly the Best Part of the Movie

Actionable Insights for Readers and Parents

If you’re looking to dive back into this world or introducing it to a new reader, here is how to get the most out of it:

Don't worry about the "dated" tech. Treat it like a period piece. The "Stormbreaker" computers are the MacGuffin. Focus on the tradecraft. Alex using his environment to escape a car crusher is a masterclass in creative problem-solving.

Read for the "Gray" areas. Encourage younger readers to think about whether MI6 is actually "right" to use Alex. It’s a great jumping-off point for discussions about ethics and the "greater good."

Watch the pacing. If you’re a writer, study how Horowitz moves the plot. Notice how he never lets Alex rest for more than a few pages. This is why the book is often cited as the "gateway drug" for reluctant readers.

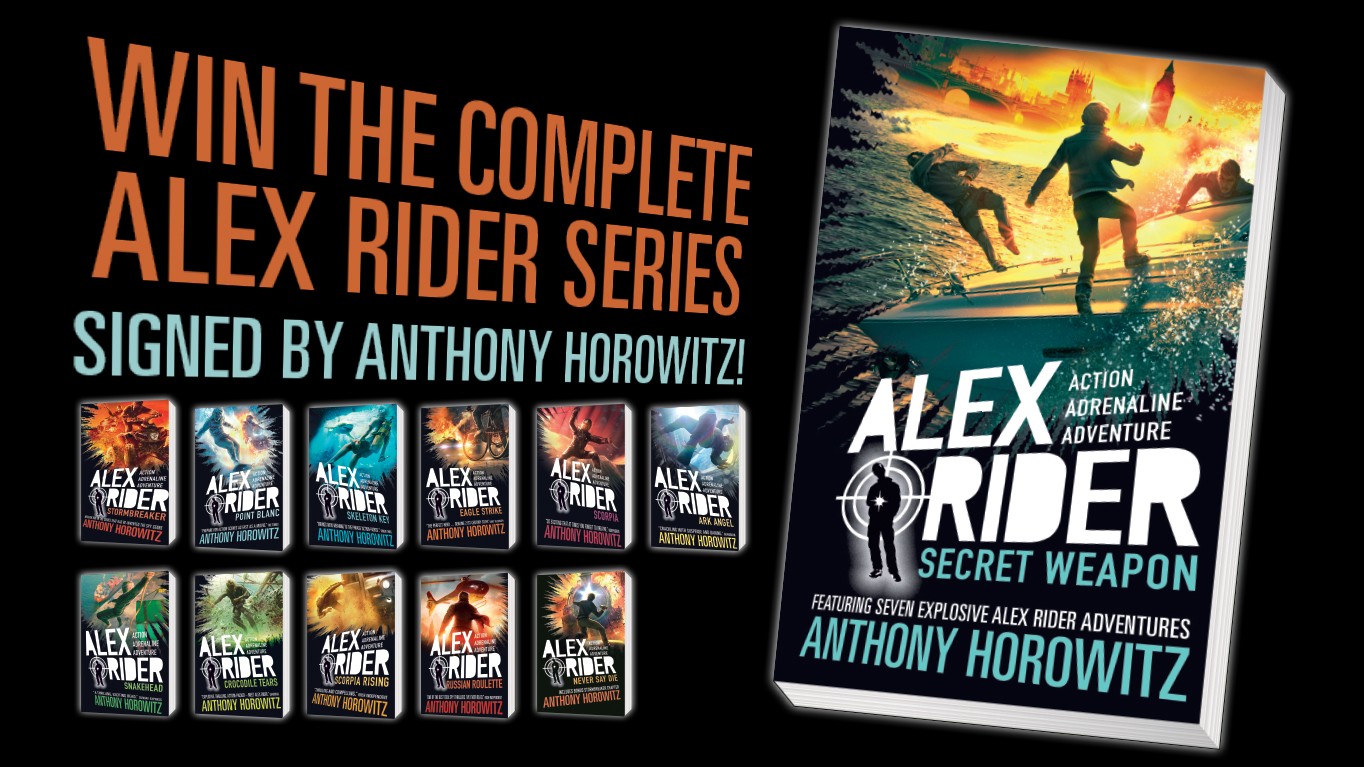

Check the sequels. While Stormbreaker is the foundation, the series actually peaks around book 4 (Eagle Strike) and book 5 (Scorpia). The first book sets up the mystery of Alex's father, which becomes the emotional core of the later novels.

Verify the editions. There are "Anniversary Editions" out there with extra materials and updated covers. If you’re a collector, look for the original 2000 Walker Books hardback—it’s a piece of YA history.

Ultimately, the Alex Rider series book 1 isn't just a nostalgia trip. It’s a tightly wound thriller that respects its audience enough to be dangerous. It doesn't offer easy answers or a perfectly happy ending. Alex saves the day, but he’s still an orphan, he’s still alone, and he’s still a pawn in a game he never asked to play. That honesty is why we’re still talking about it twenty-six years later.