You’re sitting in a cold exam room, clutching your stomach, and the doctor starts talking about "craters" in your lining. It sounds terrifying. Naturally, the first thing most people do is pull out their phone to search for pictures of stomach ulcers to see what the damage actually looks like. But here’s the thing: a grainy JPEG on a search engine doesn't always tell the whole story of what's happening inside your gut.

Ulcers are weird. They aren't just "sores." They are actual breaks in the mucosal lining of the stomach or duodenum. Think of it like a pothole in a road that goes all the way through the asphalt into the dirt below.

Most of the time, when you look at clinical images, you’re seeing the result of an EGD (Esophagogastroduodenoscopy). A tiny camera goes down the throat, and suddenly, the doctor is staring at a white, yellowish, or even red-rimmed hole. It’s visceral. It’s also incredibly common. According to the American College of Gastroenterology, about four million people in the U.S. have active peptic ulcers at any given time.

What do pictures of stomach ulcers actually show?

If you look at a high-definition image from a modern endoscopy, the first thing you’ll notice is the color contrast. The healthy stomach lining is usually a vibrant, moist pink. An ulcer, however, looks like a distinct "punched-out" area. It’s often covered in a layer of white or grayish exudate, which is basically a mix of protein and dead cells.

It looks like a shallow crater. Sometimes the edges are clean and sharp; other times they are swollen and angry-looking.

The appearance changes depending on the stage of the ulcer. A "clean-based" ulcer is usually a good sign—it means it isn’t currently bleeding. But if you see an image with a dark spot in the center, that’s often a "visible vessel." That’s a medical red flag. It means there’s a blood vessel exposed that could start gushing at any moment. Doctors use the Forrest Classification system to grade these based on how likely they are to bleed again.

Honestly, seeing the photos can be a bit of a reality check. When you see that raw, exposed tissue, you finally understand why that cup of coffee or that spicy taco feels like liquid fire. Your stomach acid, which is strong enough to dissolve metal, is literally eating into your own flesh because the protective mucus layer has failed.

🔗 Read more: No Alcohol 6 Weeks: The Brutally Honest Truth About What Actually Changes

The H. pylori Factor

For decades, everyone thought ulcers were caused by stress or bad bosses. Then came Barry Marshall and Robin Warren. These two Australian researchers discovered Helicobacter pylori, a spiral-shaped bacterium that lives in the stomach. Marshall was so sure about it that he actually drank a beaker of the bacteria to prove it caused gastritis. He won a Nobel Prize for that.

When you look at microscopic pictures of stomach ulcers or the tissue around them, you can sometimes see these little bacteria burrowed into the mucus. They secrete an enzyme called urease, which neutralizes stomach acid just enough for them to survive, but in the process, they create an inflammatory mess that leads to the ulcer.

It's not just about the hole in the stomach

There are different types of ulcers, and they don’t all look the same in photos. Gastric ulcers are in the stomach itself. Duodenal ulcers are just past the stomach in the first part of the small intestine.

Duodenal ulcers are actually more common. If you saw a picture of one, it might look a bit more cramped because the duodenum is narrower than the stomach. Interestingly, people with duodenal ulcers often feel better after eating, while those with gastric ulcers feel worse. It’s a classic diagnostic clue.

NSAIDs—stuff like ibuprofen, naproxen, and aspirin—are the other big culprits. If you take these frequently for back pain or headaches, they can block the prostaglandins that protect your stomach lining. NSAID-induced ulcers often look "multiple." Instead of one big crater, a doctor might see several small erosions scattered across the lining. They look like little red pockmarks.

Why some images look "bloody"

A bleeding ulcer is a medical emergency. In these pictures of stomach ulcers, the view is often obscured by bright red blood or dark, "coffee-ground" looking clots.

💡 You might also like: The Human Heart: Why We Get So Much Wrong About How It Works

The doctor has to wash the area with water through the endoscope just to find the source. Once they find the bleeder, they can use clips, heat probes, or injections of adrenaline to stop it. It’s pretty amazing tech. You’re basically watching a plumber fix a leak from the inside out.

If an ulcer isn't treated, it can keep digging. Eventually, it can go through the entire wall of the stomach. This is called a perforation. In a photo of a perforated ulcer, you’re literally looking through a hole in the stomach into the abdominal cavity. That’s a surgical "go-to-the-OR-now" situation.

Interpreting what you see online

The internet is full of "medical" images that are actually just stock photos or, worse, mislabeled. If you're looking at pictures of stomach ulcers online, be careful. A lot of images labeled as ulcers are actually just "gastritis," which is more like a bad sunburn on the stomach lining rather than a deep hole.

Gastritis looks like streaky redness. It’s irritated, sure, but it hasn't reached that "crater" stage yet.

Also, cancer can sometimes look like an ulcer. This is why gastroenterologists almost always take a biopsy of a gastric ulcer. They use tiny forceps to snip a piece of the edge. Malignant ulcers often have irregular, heaped-up borders. They don't look as "clean" as a standard peptic ulcer. It’s a nuance that even experienced doctors sometimes find tricky without lab results.

The healing process

The cool thing is that the human body is incredibly good at fixing itself if you give it the right tools. If you look at follow-up pictures of stomach ulcers after a few weeks of Proton Pump Inhibitor (PPI) therapy—drugs like omeprazole—the change is night and day.

📖 Related: Ankle Stretches for Runners: What Most People Get Wrong About Mobility

The white crater starts to fill in with new, pink tissue called granulation tissue. Eventually, it leaves a small scar. The lining might look a little puckered at that spot, but the danger is gone.

Actionable steps for your gut health

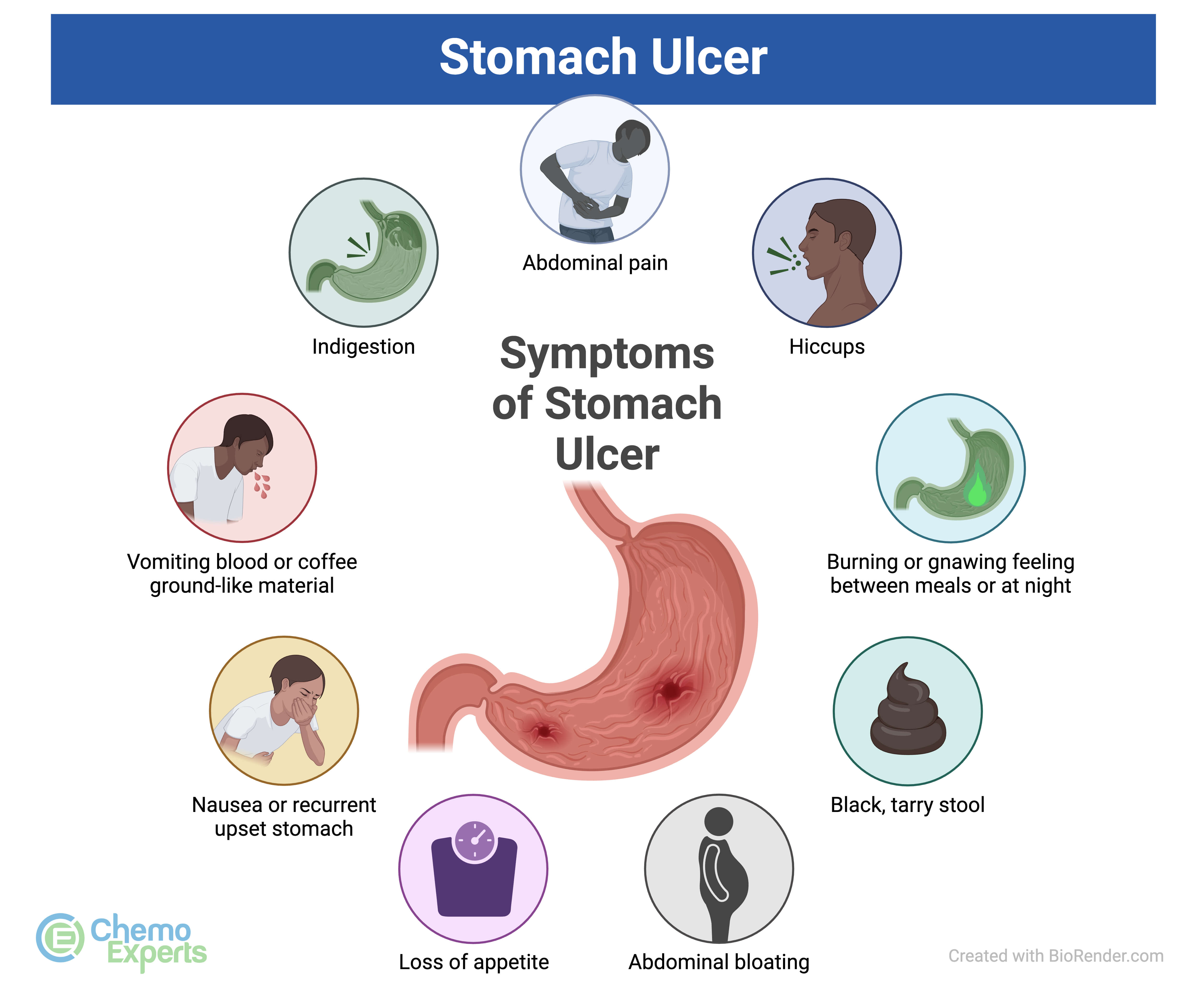

If you're searching for these images because you have gnawing pain, bloating, or dark stools, don't just stare at photos. Do something about it.

First, check your meds. Are you popping Advil like candy? Stop. Talk to a doctor about alternatives like acetaminophen, which doesn't eat your stomach lining.

Second, get tested for H. pylori. It’s a simple breath or stool test. If you have it, a round of antibiotics can cure the ulcer for good. Without killing the bacteria, the ulcer will just keep coming back, no matter how much Maalox you drink.

Third, watch for "alarm symptoms." If you’re vomiting blood (it looks like coffee grounds) or if your poop is black and tarry, stop reading and go to the ER. Those are signs of a bleeding ulcer that needs immediate attention.

Lastly, don't self-diagnose. You might think you have an ulcer, but it could be gallbladder issues, GERD, or even functional dyspepsia. An endoscopy is the gold standard. It’s a 15-minute procedure where you’re usually under "twilight" sedation—you won't remember a thing, but your doctor will come out with the actual pictures of your stomach to show you exactly what's going on.

Ulcers are manageable. We aren't in the 1950s anymore where people had to have half their stomachs removed for a simple sore. Modern medicine—specifically the discovery of H. pylori and the invention of PPIs—has made this a treatable, often curable condition. Focus on the healing, not just the scary images.