If you’ve ever stared at a blurry, grainy picture of an ulcer in the stomach handed to you by a doctor after an endoscopy, you know that sinking feeling. It looks like a crater on the moon. Or maybe a weird, angry volcano. Honestly, most people just see a mess of pink and white tissue and wonder if their insides are falling apart.

It’s scary.

But here’s the thing: seeing the ulcer is actually the "good" part of the process because it means the guesswork is over. You aren't just "having indigestion" anymore. You have a visual diagnosis. Most of these images come from an esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD). That’s a mouthful, so doctors just call it an endoscopy. They slide a tiny camera down your throat while you’re (hopefully) having a very nice propofol nap, and they snap photos of your gastric mucosa.

What does a picture of an ulcer in the stomach really show?

When you look at a medical photo of a peptic ulcer, you aren't just seeing a "sore." You’re seeing a literal hole in the lining of your stomach. The stomach has this incredibly thick, gooey layer of mucus designed to protect it from its own acid. I mean, stomach acid is basically battery acid. It has a pH of about 1.5 to 3.5. If you dropped a piece of metal in there, it would dissolve.

In a healthy picture of an ulcer in the stomach, the surrounding tissue looks like shiny, wet, pale pink silk. The ulcer itself usually looks like a distinct, punched-out circle. It’s often white or yellow in the center. That’s not "pus" usually; it’s fibrin. Fibrin is a protein that your body uses to try and scab over the wound, but since it’s underwater (well, under acid), it looks like a thick, creamy coating.

Sometimes the edges are red and swollen. Doctors call this "edema." If the photo shows dark spots or something that looks like coffee grounds, that’s a sign of recent bleeding. It’s old blood that has been "cooked" by the stomach acid.

💡 You might also like: Finding the Healthiest Cranberry Juice to Drink: What Most People Get Wrong

The H. pylori Factor and why your stomach is mad

For a long time, everyone thought ulcers were just caused by stress or eating too many jalapeño poppers. We were wrong. In 1982, two Australian researchers, Barry Marshall and Robin Warren, discovered that a bacteria called Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) was the real villain.

Marshall was so sure about this that he actually drank a beaker of the bacteria to prove it caused ulcers. He got sick, cured himself with antibiotics, and eventually won a Nobel Prize. Total legend move.

When you see a picture of an ulcer in the stomach, there’s a high chance H. pylori is the reason that hole exists. The bacteria burrow into the mucosal lining, weakening it so the acid can get through. It’s like termites in a house. The photo doesn't show the bacteria—they’re way too small—but it shows the demolition they left behind.

NSAIDs: The other culprit

Not every ulcer is bacterial. If you pop ibuprofen (Advil/Motrin) or naproxen (Aleve) like they’re candy for your back pain or headaches, you might be looking at an NSAID-induced ulcer. These drugs block prostaglandins, which are the chemicals that tell your stomach to produce that protective mucus. No mucus, no protection. The acid just eats the wall.

How doctors read the "Geography" of your stomach

Where the ulcer is located matters a lot. If it’s in the stomach, it’s a gastric ulcer. If it’s just past the stomach in the beginning of the small intestine, it’s a duodenal ulcer.

📖 Related: Finding a Hybrid Athlete Training Program PDF That Actually Works Without Burning You Out

- Gastric Ulcers: These often hurt more right after you eat because eating triggers acid production.

- Duodenal Ulcers: These are "sneaky." They often hurt when your stomach is empty—like at 2:00 AM—and feel better when you eat something.

In a picture of an ulcer in the stomach, the doctor is looking for specific "red flags." They want to see if the borders are smooth and regular. If the edges look ragged, heaped up, or irregular, they get worried about gastric cancer. This is why almost every time a doctor sees an ulcer in a photo, they take a tiny "snip" of it—a biopsy—to send to a lab. It’s standard procedure. Don't panic if they say they took a biopsy; it’s just due diligence.

Can you feel what the picture shows?

Symptoms are weirdly inconsistent. Some people have a massive, deep ulcer that looks terrifying in a photo, but they barely feel a twinge. Others have a tiny "aphthous" ulcer—basically a canker sore in the stomach—and they’re in agony.

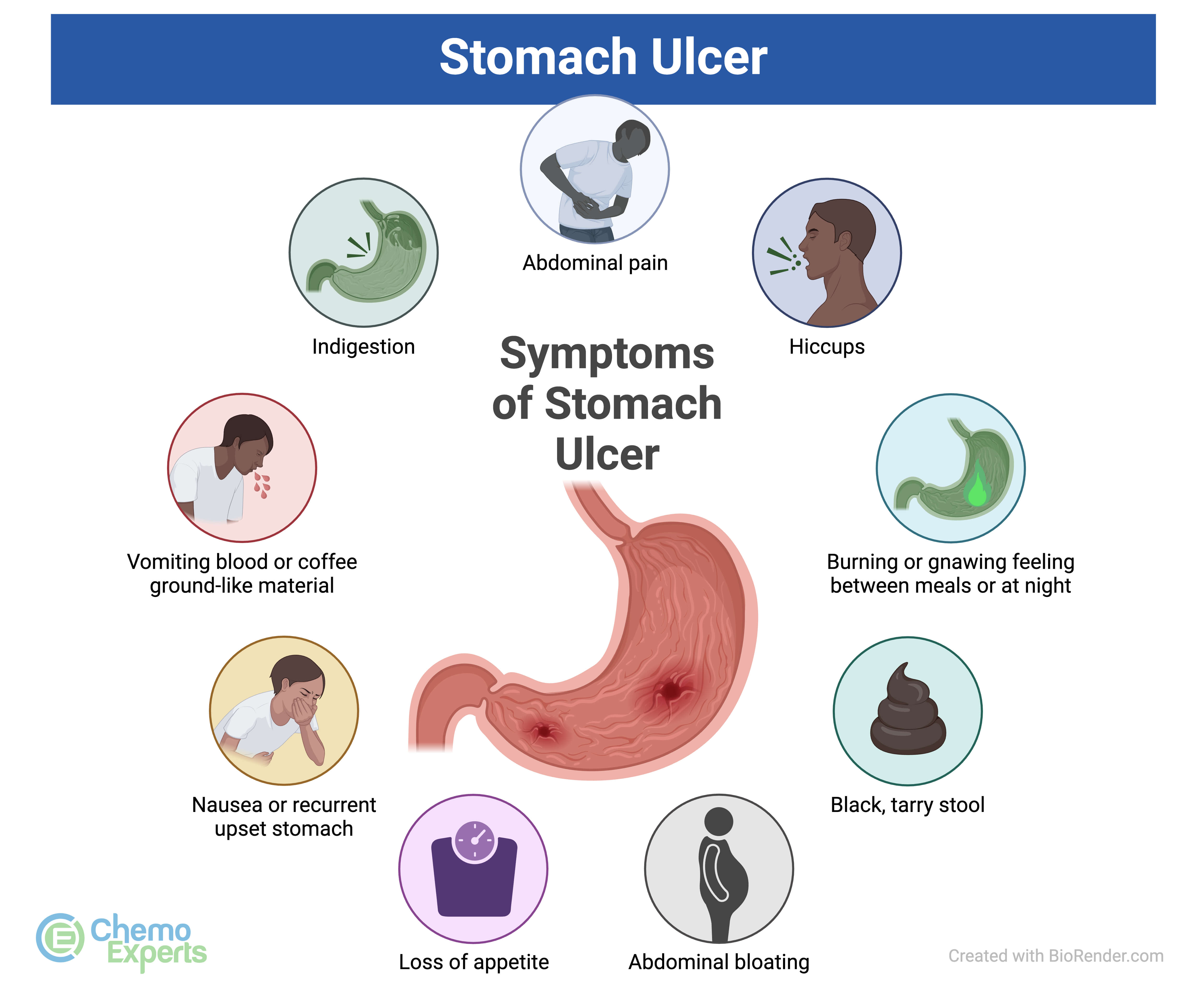

Common symptoms usually include:

- A gnawing or burning pain in the middle of your abdomen.

- Bloating or feeling full way too fast.

- Nausea that comes and goes.

- Heartburn that doesn't respond to Tums anymore.

If the picture of an ulcer in the stomach shows a "perforation," that’s a medical emergency. That means the hole went all the way through the stomach wall. That causes "peritonitis," which is basically your stomach contents leaking into your abdominal cavity. It hurts like nothing else. If you ever have "board-like" abdominal rigidity or pain so sharp you can't move, go to the ER. Don't wait for a photo.

Healing: What the "After" picture looks like

The cool thing about the stomach is that it heals remarkably fast. If you go on a Proton Pump Inhibitor (PPI) like omeprazole or lansoprazole, you’re basically turning off the acid spigot. This gives the ulcer a chance to scab over and grow new tissue.

👉 See also: Energy Drinks and Diabetes: What Really Happens to Your Blood Sugar

In a follow-up picture of an ulcer in the stomach taken 8 weeks later, you often can’t even see where the hole was. The white fibrin is gone. The red, angry edges have flattened out. The tissue looks like that healthy pink silk again. It’s actually pretty incredible how the body patches itself up once you stop the acid attack.

What you should do next

If you have a copy of your endoscopy report and you're staring at that picture of an ulcer in the stomach, here are the actual steps you need to take.

First, check the biopsy results. This usually takes 3 to 7 days. This will tell you if H. pylori was present. If it was, you’ll be on a "triple therapy" or "quadruple therapy"—a mix of two or three antibiotics and a PPI for about two weeks. Finish the whole bottle. Even if you feel better on day four. If you don't kill the bacteria, the ulcer will just come back.

Second, look at your meds. If you take aspirin for your heart or NSAIDs for arthritis, talk to your doctor about alternatives. Acetaminophen (Tylenol) doesn't cause ulcers, so it’s usually the safer bet for pain, though it doesn't help with inflammation the same way.

Third, lifestyle stuff. You don't need to live on a "bland diet" of boiled chicken and white rice forever. That's old-school advice. However, while the ulcer is active—while it looks like that crater in the photo—avoid things that irritate it. Alcohol is a big one. It’s a direct irritant to the stomach lining. Smoking is another; it slows down the blood flow to the stomach, which prevents healing.

Finally, schedule your follow-up. If it was a gastric ulcer, most GI docs want a second picture of an ulcer in the stomach after your treatment is done. They want to be 100% sure it’s gone and that no underlying issues were hiding beneath the inflammation. It’s an extra step, but it’s the only way to be sure you're actually in the clear.