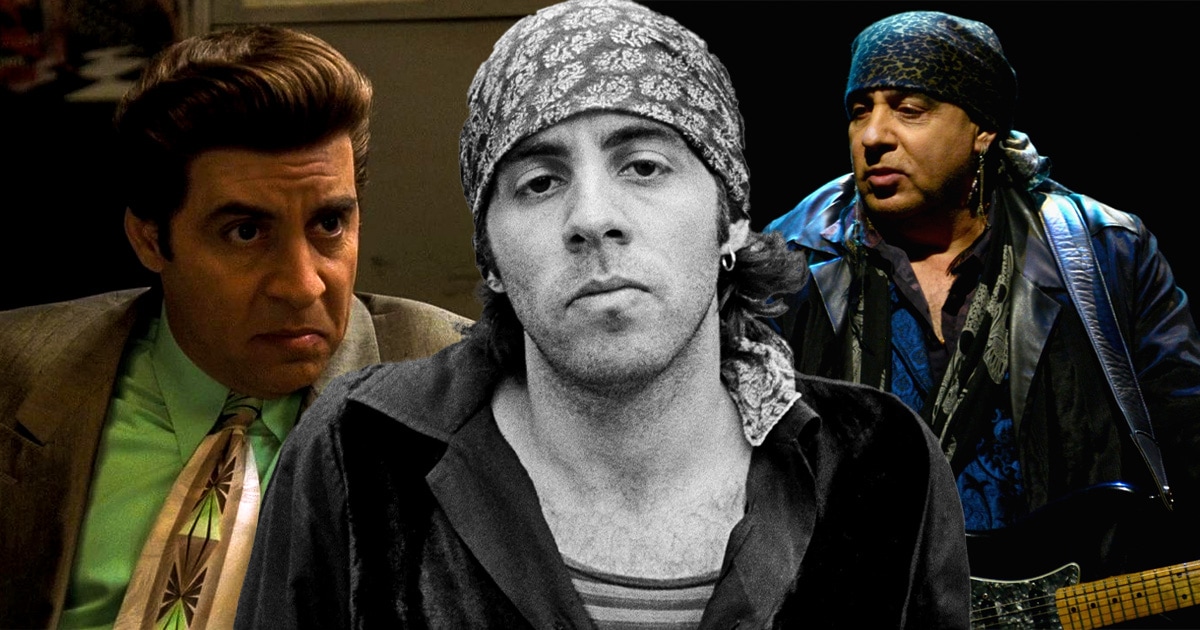

You’ve seen the bandana. You’ve seen the scowl. Whether it’s as Silvio Dante leaning against the bar at the Bada Bing or as the guy stage-right of Bruce Springsteen, Steven Van Zandt is one of those figures who seems like he’s just always been there. A permanent fixture in the bedrock of American culture.

But honestly? Most people only know about ten percent of what this guy has actually done.

It’s easy to dismiss him as the "sidekick." That’s a mistake. In the world of rock and roll, being a sidekick to The Boss isn't just about playing guitar; it’s about being the architect of a sound that defined an era. And in 2026, as the music industry feels more like a series of TikTok algorithms than a soulful movement, the career of Steven Van Zandt—musician, activist, actor, and educator—looks less like a history lesson and more like a blueprint for survival.

The Jersey Shore Sound wasn't an Accident

People talk about the "Jersey Shore sound" like it just floated in off the Atlantic. It didn't. Steven Van Zandt basically built it with his bare hands.

Before the stadiums, before the Super Bowl halftime shows, Van Zandt was the guy in the trenches of Asbury Park. He wasn't just playing; he was arranging. He took the grit of R&B, the polish of Motown, and the raw energy of British Invasion rock and smashed them together.

If you listen to the early Southside Johnny and the Asbury Jukes records—specifically I Don't Want to Go Home—that's Van Zandt's vision. He was the one writing the horn charts. He was the one making sure the "Miami Steve" persona felt authentic. Without him, Springsteen’s Born to Run might have sounded like a folk record. It was Van Zandt who walked into the studio and fixed the horn arrangement for the title track when things were stalling. He didn't even have a contract at the time. He just did it because the music needed to be right.

Why He Quit (And Why He Came Back)

In 1984, Van Zandt did the unthinkable. He walked away from the biggest band in the world right as they were about to hit the Born in the U.S.A. stratosphere.

Why? Because he had something to say, and he couldn't say it from the back of the stage.

👉 See also: The Entire History of You: What Most People Get Wrong About the Grain

This is where the Steven Van Zandt musician story takes a sharp turn into "Artist as Activist." He didn't just write a protest song; he organized a movement. Artists United Against Apartheid was his brainchild. He saw what was happening in South Africa and realized that musicians were being paid blood money to play at the Sun City resort.

He didn't just tweet about it. He flew to South Africa. He did the research. He recruited everyone from Bob Dylan to Miles Davis to Lou Reed for the "Sun City" track.

"I hate bullies. Always have. So I’m kind of attracted to fighting them whenever possible."

That quote from his recent retrospective perfectly sums up the vibe. He wasn't looking for a "We Are The World" singalong. He wanted to hit the regime where it hurt: the wallet. And it worked. Most political experts agree that the cultural boycott he spearheaded was a massive catalyst in the eventual fall of apartheid.

The Sopranos and the "Accidental" Acting Career

Fast forward to the late 90s. David Chase is looking for a guy to play a mobster. He sees Van Zandt inducting The Rascals into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and thinks, "That’s my guy."

Van Zandt had never acted. Not a day in his life.

But he stepped into the role of Silvio Dante and created an icon. The hair, the hunch, the weirdly specific way he moved—it wasn't a caricature. It was a character he built from the ground up. He even insisted on a character that didn't really exist in the pilot so he wouldn't take a job away from a "real" actor.

✨ Don't miss: Shamea Morton and the Real Housewives of Atlanta: What Really Happened to Her Peach

Then came Lilyhammer. It was Netflix's first-ever original series. People forget that. Before Stranger Things or House of Cards, there was Steven Van Zandt as a mobster in witness protection in Norway. He didn't just act in it; he wrote it, produced it, and composed the score. He was a pioneer of the "binge-watch" era before we even had a name for it.

Surviving 2025 and Beyond

Even legends have bad days. In June 2025, while on the European leg of the "Land of Hope and Dreams" tour, Van Zandt had a major health scare.

He started feeling sharp pains in his stomach in San Sebastián, Spain. Being the tough guy he is, he figured it was just bad seafood. Food poisoning. Standard tour hazard, right?

Nope. Appendicitis.

He ended up in emergency surgery. He had to miss a handful of shows—a rarity for a guy who lives on the road. But the recovery was fast. By the time the tour hit Milan in July 2025, he was back on stage. It was a reminder that even at 74 (he’s 75 now), the man is seemingly made of leather and guitar strings.

The TeachRock Revolution

If you want to know what Steven Van Zandt is most proud of today, it’s not the gold records. It’s TeachRock.

He noticed that kids were dropping out of school because they felt disconnected from the curriculum. His solution? Use the history of popular music to teach everything else.

🔗 Read more: Who is Really in the Enola Holmes 2 Cast? A Look at the Faces Behind the Mystery

- History: Teach the Civil Rights movement through the lens of Sam Cooke.

- Science: Explain sound waves and technology through the evolution of the electric guitar.

- Math: Use the business of the music industry to teach data and statistics.

By 2026, TeachRock is being used by over 80,000 teachers and reaching more than a million students. It’s a free, standards-aligned curriculum. He’s essentially hacked the education system by making it cool again. He calls it "STEAM" (Science, Technology, Engineering, Arts, and Math), and it’s actually working. Chronic absenteeism in schools using the program has dropped significantly.

The Reality of Rock in 2026

Van Zandt has been vocal about the "death" of classic rock. He’s not being a hater; he’s being a realist. He sees a world where the infrastructure that built bands like the E Street Band—local radio, record stores, a common cultural language—is disappearing.

His response? Little Steven's Underground Garage.

His radio show and SiriusXM channel aren't just nostalgia trips. He uses his platform to highlight new bands that still have that "garage rock" spirit. He’s playing the long game, trying to preserve the DNA of rock and roll so it doesn't just become a museum piece.

When you look at his solo work, like the 2019 Summer of Sorcery or his 2021 memoir Unrequited Infatuations, you see a man who is constantly evolving while staying rooted in his core values. He doesn't write political songs anymore because, as he puts it, "it’s all right in your face now." Instead, he tries to provide "sanctuary." He wants the music to be a place where people with different opinions can still stand in a room together and feel something.

How to Follow the Van Zandt Blueprint

If you’re a musician or a creative looking at Steven Van Zandt’s career, the takeaway isn't "get a job with a superstar." It’s "become indispensable."

- Be a "Generalist Expert": Van Zandt succeeded because he understood the horn section, the rhythm section, the business of radio, and the mechanics of a TV script.

- Use Your Platform Early: Don't wait until you're "famous enough" to care about a cause. He was fighting apartheid when it was still a fringe issue in the US.

- Education is the Only Way Forward: Whether it’s mentoring younger players or building a curriculum, he’s focused on the next generation.

Steven Van Zandt isn't just a musician. He’s a cultural preservationist. In a world of fleeting digital fame, he’s a reminder that craftsmanship, loyalty, and a really good hat can carry you through half a century of change.

Next Steps for the Van Zandt Superfan:

Check out the TeachRock website if you’re an educator or parent; the lesson plans on the history of the Blues are particularly deep. If you haven't seen the HBO documentary Stevie Van Zandt: Disciple, watch it for the never-before-seen footage of the early Jersey Shore days. Finally, if you're a musician, listen to the production on The River—notice how the guitars and drums sit in the mix. That's the Van Zandt touch.