Steve McQueen didn't just want to make a movie about racing. He wanted to capture the literal soul of speed, even if it meant setting his entire life on fire to do it. Honestly, if you look at the production of the 1971 film Le Mans, it wasn't just a "troubled shoot"—it was a psychological car wreck that nearly ended the career of the biggest movie star in the world.

The story of Steve McQueen man and Le Mans is basically a cautionary tale about what happens when a man’s obsession outweighs his common sense. By 1970, McQueen was the "King of Cool," fresh off the massive success of Bullitt. He had the money, the power, and a production company called Solar Productions that gave him a blank check. He decided to use that check to film the 24 Hours of Le Mans in France.

He didn't want a script.

He didn't want a traditional plot.

He just wanted the cars.

The Chaos of Steve McQueen Man and Le Mans

The documentary Steve McQueen: The Man & Le Mans (2015) pulls back the curtain on just how dark things got in the French countryside. McQueen moved his entire family, including his wife Neile Adams and their kids, to a villa in France. But he wasn't exactly playing the family man. While he was obsessing over camera angles on the Porsche 917, his marriage was disintegrating. Neile later admitted it was a "horror" period. McQueen was reportedly having an affair with Swedish actress Louise Edlind and, in a moment of pure recklessness, crashed a car while driving her back to her hotel at 2:00 AM.

They had to hush it up.

💡 You might also like: Why the Jordan Is My Lawyer Bikini Still Breaks the Internet

But you can't hush up a lack of a script when you have a crew of hundreds sitting around in the rain. John Sturges, the legendary director who gave McQueen his big breaks in The Magnificent Seven and The Great Escape, was the original director. He eventually walked away in total disgust. Imagine being one of the top directors in Hollywood and having your lead actor tell you, "We don't need a story, John. We just need the racing." Sturges famously said, "I'm too old and too rich to put up with this," and hopped on a plane back to the States.

Lee H. Katzin took over, but the damage was done. The production was months behind. The studio, Cinema Center Films, was hemorrhaging cash. At one point, they shut the whole thing down for two weeks just to figure out if there was even a movie to save.

Why the 1970 Race Was Different

What makes the Steve McQueen man and Le Mans story so visceral is the actual danger involved. This wasn't CGI. This wasn't "movie magic" with cars on trailers. They were driving at nearly 200 mph.

McQueen actually wanted to drive in the real 1970 race. He'd just come off a second-place finish at the 12 Hours of Sebring (driving with a broken foot, because of course he was), and he was convinced he could handle the Sarthe circuit. The insurance companies, predictably, lost their minds. They forbade him from entering.

Instead, Solar Productions entered a Porsche 908 as a "camera car." It was driven by Herbert Linge and Jonathan Williams. They had to stop constantly to change film reels, which is basically the opposite of what you want to do in an endurance race.

Amazingly, they still finished 9th overall.

📖 Related: Pat Lalama Journalist Age: Why Experience Still Rules the Newsroom

They weren't officially classified because they didn't cover enough distance (thanks to those pit stops), but it proved McQueen's point: the footage was real. It was raw.

The High Cost of Authenticity

But authenticity has a body count. David Piper, a professional driver, had a horrific crash during a staged sequence. His car flipped, and he ended up losing part of his leg. McQueen was devastated, but the machine kept rolling. Derek Bell, another racing legend, nearly got roasted alive when his Ferrari 512 burst into flames during a shot.

The movie basically became a ghost ship. McQueen lost control of his company. He lost his friend and producer Bob Relyea. He almost lost his life when he realized he was on Charles Manson’s "hit list" back in California—a revelation that hit him right in the middle of this French meltdown.

When Le Mans finally hit theaters in 1971, it was a massive flop.

The first 37 minutes have almost zero dialogue.

Critics hated it. General audiences were bored by the lack of a "Hollywood" love story. McQueen didn't even attend the premiere. He was done with it. He was broken by it.

👉 See also: Why Sexy Pictures of Mariah Carey Are Actually a Masterclass in Branding

The Legacy of a Failure

The irony is that today, Le Mans is considered the greatest racing movie ever made. It’s not because of the acting—it’s because McQueen was right. He captured the 1970s era of racing with a fidelity that no one has ever matched. You can smell the castor oil and the scorched rubber when you watch it.

The documentary Steve McQueen: The Man & Le Mans really highlights this "vindication." His son, Chad McQueen, often talked about how professional drivers still come up to him and say that film was the reason they started racing. It wasn't for the "general public." It was for the guys who lived in the cockpit.

Actionable Insights for Fans and Historians

If you want to truly understand the Steve McQueen man and Le Mans saga, don't just watch the 1971 movie. You've got to dig into the context.

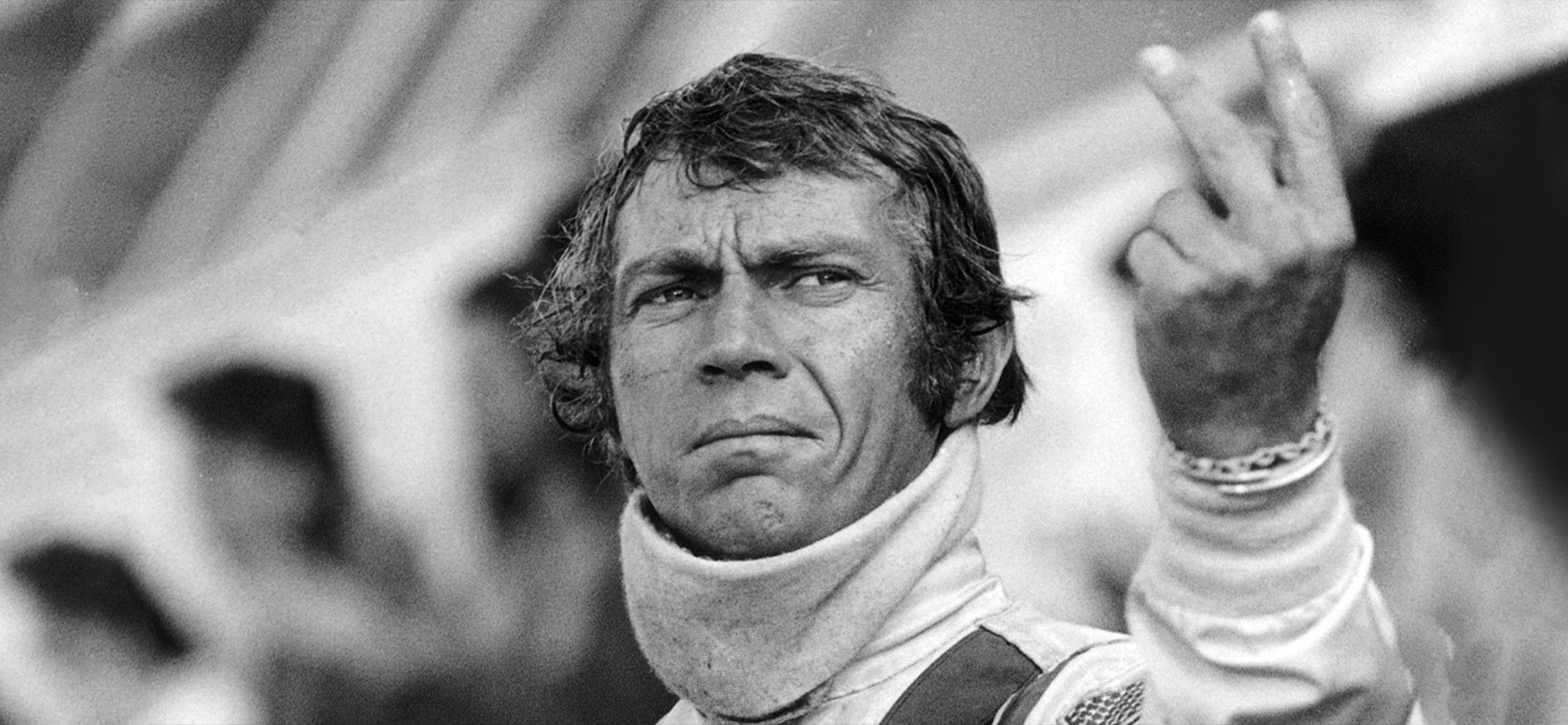

- Watch the 2015 Documentary: It uses discovered footage from the set that sat in a basement for decades. It shows the tension on McQueen's face that the movie hides.

- Compare it to "Grand Prix" (1966): To see why McQueen was so frustrated, watch the rival film by John Frankenheimer. It's more of a "movie," whereas McQueen wanted a "document."

- Look at the Cars: The Porsche 917 and Ferrari 512 are the real stars. Researching the "camera car" (the 908) gives you a huge appreciation for the technical hurdles they jumped.

- Read "French Kiss with Death": If you want the gritty, day-by-day breakdown of the disasters on set, this book by Michael Keyser is the gold standard.

Ultimately, McQueen's obsession with Le Mans cost him his marriage and his status as a studio power player. He never really recovered that "King of Cool" untouchability afterward. But he left behind a piece of film that serves as a time capsule for a lethal, beautiful era of motorsport. He didn't make a movie; he made a monument.

Next Steps for Deep Diving:

Check out the archival interviews of Neile Adams regarding the 1970 shoot. Her perspective as the person trying to hold the family together while McQueen "chased ghosts" on the track provides the necessary human contrast to the mechanical obsession of the film. It's the only way to see the man behind the helmet.