A few weeks after Steve Jobs died in 2011, PBS aired a documentary that felt a little like an emergency broadcast for the soul of Silicon Valley. It was called Steve Jobs: One Last Thing. At the time, the world was drowning in "iTributes." People were leaving half-eaten apples on the sidewalks in front of Apple Stores, and the collective grief was weirdly intense for a guy who sold $2,000 laptops.

But this film wasn't just another highlight reel of product launches.

It tried to get into the "why." Why did a guy who was notoriously difficult to work with—and sometimes just plain mean—manage to make people feel like they lost a family member? Honestly, the documentary succeeds because it doesn't try to polish the rough edges. It shows the "misfit" and the "tyrant" right alongside the "genius."

What Steve Jobs: One Last Thing Actually Revealed

The most famous part of this documentary is a "lost" interview from 1994. Back then, Jobs was basically in exile. He had been kicked out of Apple and was running NeXT, a company that was doing cool things but failing commercially. He had a shaggy beard and looked more like a philosophy professor than a billionaire.

In that footage, he says something that basically defines his entire life's work. He talks about how most people live life "trying not to bash into the walls too much." They accept the world as it is. But Jobs argues that once you realize the world was built by people "no smarter than you," you can change it. You can poke it. You can move the walls.

That’s the core of Steve Jobs: One Last Thing. It’s not about the iPhone; it’s about the audacity to think you’re allowed to redesign reality.

The People Who Actually Knew Him

The film pulls in a heavy-hitting roster of people who didn't just watch Jobs from afar. We're talking about the people who got the 2:00 AM phone calls and the "Reality Distortion Field" treatment.

- Steve Wozniak: "The Woz" is there, and he's as vulnerable as ever. He talks about the early days and the pure joy of making things just to see if they’d work. There’s a sadness there, too—the feeling of a friendship that became a business and eventually a legend, losing the human element along the way.

- Ronald Wayne: Remember the guy who owned 10% of Apple and sold it for $800? Yeah, he’s in this. He’s interviewed in a limo in Las Vegas, and he doesn't seem bitter, which is wild. He calls Jobs "business-directed" and "extremely serious." It’s a polite way of saying the guy didn't have a "chill" mode.

- Dean Hovey: He’s the designer who built the first Apple mouse. He tells a great story about using a plastic butter dish and a roll-on deodorant ball to prototype the thing. It’s a reminder that before Apple was a trillion-dollar behemoth, it was just guys hacking stuff together in a garage.

- Bill Gates: The rivalry is legendary, but in this doc, you see the mutual respect. Walt Mossberg, the famous tech columnist, breaks down their "frenemy" dynamic. Gates basically admits he’d give a lot for Steve’s "taste."

The Complexity of the "Tyrant" Label

One thing this documentary doesn't do is shy away from the fact that Jobs could be a nightmare. Pixar co-founder Alvy Ray Smith shows up to give a reality check. He doesn't paint a picture of a saint. He describes a man who could be selfish and an "angry wheeler-dealer."

It’s an important distinction. Modern tech culture often tries to copy Jobs' intensity without having his vision. Steve Jobs: One Last Thing shows that the intensity wasn't the point—it was a byproduct of his obsession with the "best" idea. He didn't care about hierarchy; he cared about the result. If you were a junior engineer with a better idea than him, he’d yell at you, but if you were right, he’d eventually adopt your idea as his own (and probably forget it wasn't his).

The Buddhist Influence

A lot of people know Jobs was into Zen, but the film actually talks to a monk and his calligraphy teacher from Reed College, Robert Palladino. This is why the Mac had beautiful fonts while every other computer looked like a spreadsheet.

Jobs took a calligraphy class because he thought it was beautiful, not because it was "useful." Years later, that "useless" knowledge changed how we interact with screens. The documentary hammers home this idea: Steve wasn't a computer scientist. He was an artist who used silicon as his medium.

Why You Should Care Today

Watching this now, years after the 2011 premiere, feels different. We live in a world where tech feels "finished." Everything is an iteration. Another lens on a camera, a slightly faster chip.

Steve Jobs: One Last Thing reminds us of the era when tech felt like magic. It captures that specific moment in history when the tools we use today—the ones we now take for granted—were being willed into existence by a guy who refused to accept the "walls" of the world.

👉 See also: Backing Up Your Hard Drive: Why Most People Are One Click Away From Total Disaster

If you’re looking for a roadmap on how to be a "tech bro," this isn't it. If you’re looking for a study on how a singular, flawed, brilliant human being can leave a mark on the world that doesn't wash away, this documentary is basically the primary text.

Actionable Takeaways from the Jobs Philosophy

- Question the "Walls": Next time someone tells you "that's just how it's done," remember the 1994 interview. Everything around you was made by people no smarter than you.

- Value the "Useless": Jobs' interest in calligraphy and Zen didn't have an ROI at first. Don't be afraid to learn things that don't have an immediate "business case."

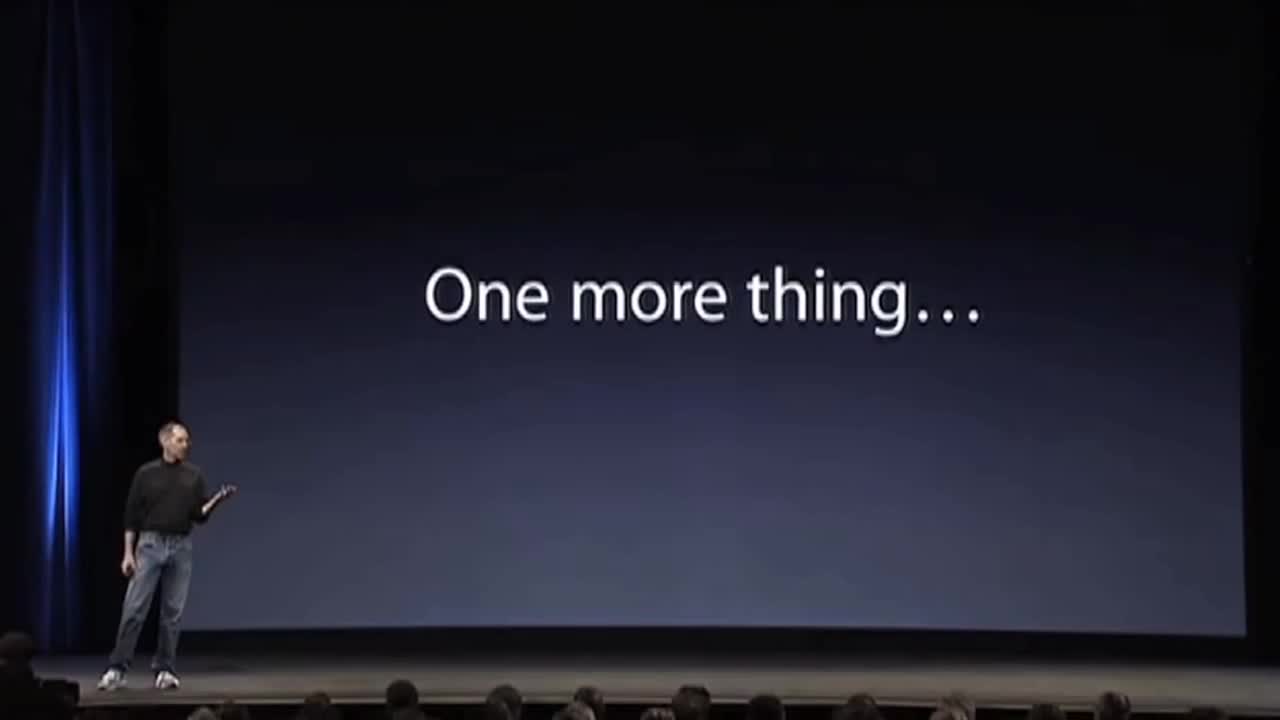

- The Power of "One Last Thing": This wasn't just a marketing trick. It was about exceeding expectations when people thought the show was over. Always look for that extra 5% of polish or surprise in your own work.

- Focus on the Idea, Not the Title: Build a culture where the best idea wins, regardless of who it comes from. It’s messy and leads to arguments, but it beats polite mediocrity every time.

To really get the most out of this, track down the full 60-minute version of the documentary. It’s often available on PBS’s archival platforms or through various streaming services. Pay close attention to the way the interviewees' eyes light up when they talk about the early days—that's the "it" factor that most modern tech companies are desperately trying to recapture.