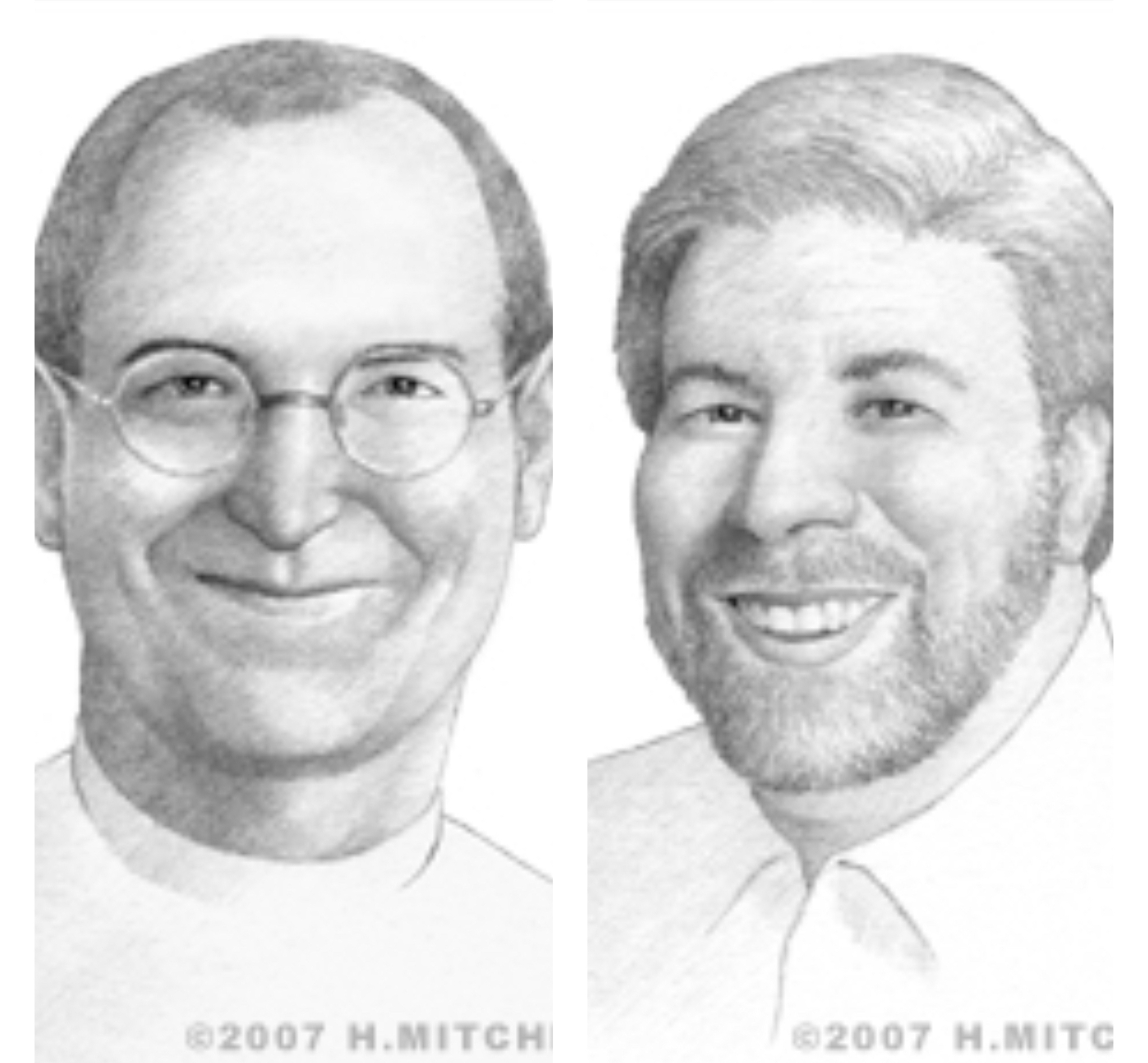

It wasn't a corporate boardroom. It was a garage in Los Altos. You’ve heard that before, right? It’s the quintessential American myth. But the reality of Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak is way more interesting than the polished "Gods of Silicon Valley" narrative we see in movies today. People tend to think of them as a singular unit—the "Steves"—but they were basically two different species of human. Without Wozniak, Jobs is just a guy with a great pitch and no product. Without Jobs, Wozniak is a brilliant engineer at HP who probably retires with a nice pension and a bunch of cool prototypes in his basement.

They needed each other. Desperately.

The Blue Box Era: Before the Apple I

Before the billion-dollar valuations, there was the "Blue Box." This is the part people forget. They were basically hackers. Wozniak read an article in Esquire about "Captain Crunch" and the world of phone phreaking. He figured out how to replicate the tones used by the telephone network to make long-distance calls for free. Honestly, it was illegal. Jobs saw it and didn't just think "cool toy." He thought "business."

Jobs realized they could sell these boxes for $150 a pop. It was the first time they tested their dynamic. Wozniak built the magic; Jobs found the audience. It almost got them arrested, but it proved something vital. You can have the best tech in the world, but if nobody buys it, it’s just a paperweight. Jobs later said that if it hadn't been for the Blue Boxes, there would have been no Apple. It gave them the confidence to take on giant systems.

The Homebrew Computer Club

The mid-70s were wild. You had all these nerds gathering at the Homebrew Computer Club, swapping parts and ideas. Wozniak was a star there. He wasn't trying to be famous. He just wanted to show off his circuit designs. When he finished the Apple I, he was actually giving the schematics away for free. Can you imagine? Jobs was the one who stepped in and said, "Hey, stop. Let’s build a PC board and sell them."

Wozniak sold his HP-65 calculator to fund the venture. Jobs sold his Volkswagen bus. They were all in. But the Apple I was barely a computer; it was just a motherboard. You had to provide your own keyboard, monitor, and housing. It was DIY. It was the Apple II, however, where the magic really happened. That was the machine that changed the world.

🔗 Read more: The MOAB Explained: What Most People Get Wrong About the Mother of All Bombs

The Apple II: Where Wozniak’s Genius Met Jobs’ Aesthetics

The Apple II was a masterpiece. Seriously. It had color graphics when everything else was text-only. It had an expansion slot architecture that was way ahead of its time. But here’s the thing: Wozniak wanted it to be a technical marvel. Jobs wanted it to be a consumer product.

Jobs insisted on a plastic case. He didn't want it to look like a piece of industrial equipment. He wanted it to look like it belonged in a kitchen or an office. This created massive friction. Wozniak was all about functionality and internal beauty—the way the chips were laid out on the board mattered to him. Jobs cared about the beige color of the plastic and the lack of a cooling fan because he hated the noise. This tension is why Apple became Apple. It was the collision of engineering purity and obsessive design.

The Breakdown of the Partnership

By the early 80s, things got weird. The IPO in 1980 made them both incredibly rich, but it changed the vibe. Wozniak started feeling alienated. Jobs was becoming the face of the company, the visionary leader of the Macintosh project, which was basically his baby. Meanwhile, Wozniak was still supporting the Apple II, which was actually the product paying all the bills.

Wozniak eventually left. He survived a plane crash in 1981, which gave him some serious perspective. He didn't want to run a company. He didn't want to play the corporate politics game. He wanted to teach. He wanted to build universal remotes (which he did with his company CL 9). People often ask if they stayed friends. Sorta. It was complicated. They weren't hanging out every weekend, but there was a deep, mutual respect that never quite died, even when Jobs was being, well, Jobs.

What Most People Get Wrong About the Jobs-Wozniak Dynamic

You see it in the biopics. Jobs is the "genius" and Woz is the "sidekick." That’s total nonsense. Wozniak’s design for the Apple II disk drive is still considered one of the most elegant pieces of engineering in the history of computing. He used a fraction of the chips that other companies used. He was a wizard.

💡 You might also like: What Was Invented By Benjamin Franklin: The Truth About His Weirdest Gadgets

On the flip side, people paint Jobs as just a "marketing guy." Also wrong. Jobs had an intuitive sense of how technology should feel. He pushed Wozniak to do things Woz didn't think were necessary, like making the computer smaller or quieter. Jobs was the curator. He wasn't the painter, but he was the guy who decided which paintings were worth putting in the gallery.

- Wozniak's Priority: Efficiency, openness, and the "joy of the build."

- Jobs' Priority: The user experience, the brand, and "denting the universe."

- The Result: A computer that people actually liked using.

The Reality of the "Garage" Myth

Research from authors like Walter Isaacson and even Wozniak himself has debunked parts of the garage story. They didn't really "design" the computers there. It was more of a staging area. They did a lot of the work at their jobs or in their own rooms. The garage makes for a better story, though. It fits the narrative of the underdog.

But does the myth matter? Not really. What matters is that they represented a shift. Before them, computers were for governments and big corporations. After them, computers were for us.

Why Their Legacy Matters in 2026

We are currently living in an era dominated by AI and closed ecosystems. Looking back at Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak reminds us that the best tech comes from the intersection of the "liberal arts and technology." Jobs talked about that a lot. It wasn’t just about the gigahertz; it was about the poetry of the machine.

Wozniak still advocates for the "right to repair" and open systems. He’s the conscience of the industry. Jobs, even years after his passing, remains the benchmark for product excellence. You can't mention a new gadget without someone asking, "What would Jobs think?"

📖 Related: When were iPhones invented and why the answer is actually complicated

Actionable Lessons from the Apple Founders

If you're trying to build something—whether it’s a startup, a piece of art, or a career—there are actual takeaways here. Don't just treat them as historical figures. Use their playbook.

First, find your opposite. If you’re a builder, find a storyteller. If you’re a dreamer, find someone who can actually solder the circuits. Solo founders are great, but the Jobs/Wozniak model proves that the friction between two different mindsets creates a spark that one person just can't generate alone.

Second, sweat the "hidden" details. Wozniak made sure the back of the circuit board was clean. Jobs made sure the inside of the Mac was beautiful, even though most people would never see it. That level of craft creates a culture of excellence that survives long after you're gone.

Finally, understand the difference between a project and a product. Wozniak had a project. Jobs turned it into a product. A project is something you do for yourself. A product is something that solves a problem for someone else. You need both to succeed.

Next Steps for Your Own Innovation

- Audit your "Inner Woz": Are you building things with technical integrity? Check your processes. Are you taking shortcuts that will hurt the product later?

- Audit your "Inner Jobs": Look at your project through the eyes of a total stranger. Is it intuitive? Does the packaging (or the presentation) match the quality of the work?

- Study the Schematics: Read Wozniak's autobiography, iWoz. It’s a masterclass in how to think about problem-solving.

- Simplify: Look at your current workload. Jobs was famous for "saying no to a thousand things." Pick the one thing that actually matters and cut the rest.

The story of the two Steves isn't just a history lesson. It's a blueprint for how to create things that last. They didn't just build a company; they built a new way for humans to interact with the world. Whether you're an engineer or an entrepreneur, you're working in the shadow of the garage. Use that.