Go to any preserved railway in the world, from the Bluebell Railway in Sussex to the Durango & Silverton in Colorado, and you’ll see the same thing. People aren't just looking at the train; they are standing perfectly parallel to the tracks, cameras gripped tight, waiting for that specific steam engine train side view. It’s the profile that does it. There is something about the horizontal sprawl of a locomotive—the massive boiler, the complicated spiderweb of driving rods, and the cab perched at the end like an afterthought—that hits differently than a modern, aerodynamic electric unit.

Modern trains are basically sleek tubes. Boring. A steam engine, though, is an exposed mechanical gut. When you look at it from the side, you aren't just looking at a vehicle; you’re looking at a live map of thermodynamics. You see the firebox where the heat starts, the long boiler where the water turns to gas, and the cylinders where that gas finally screams into motion.

It’s messy. It’s loud. It’s perfect.

The Engineering Logic of the Profile

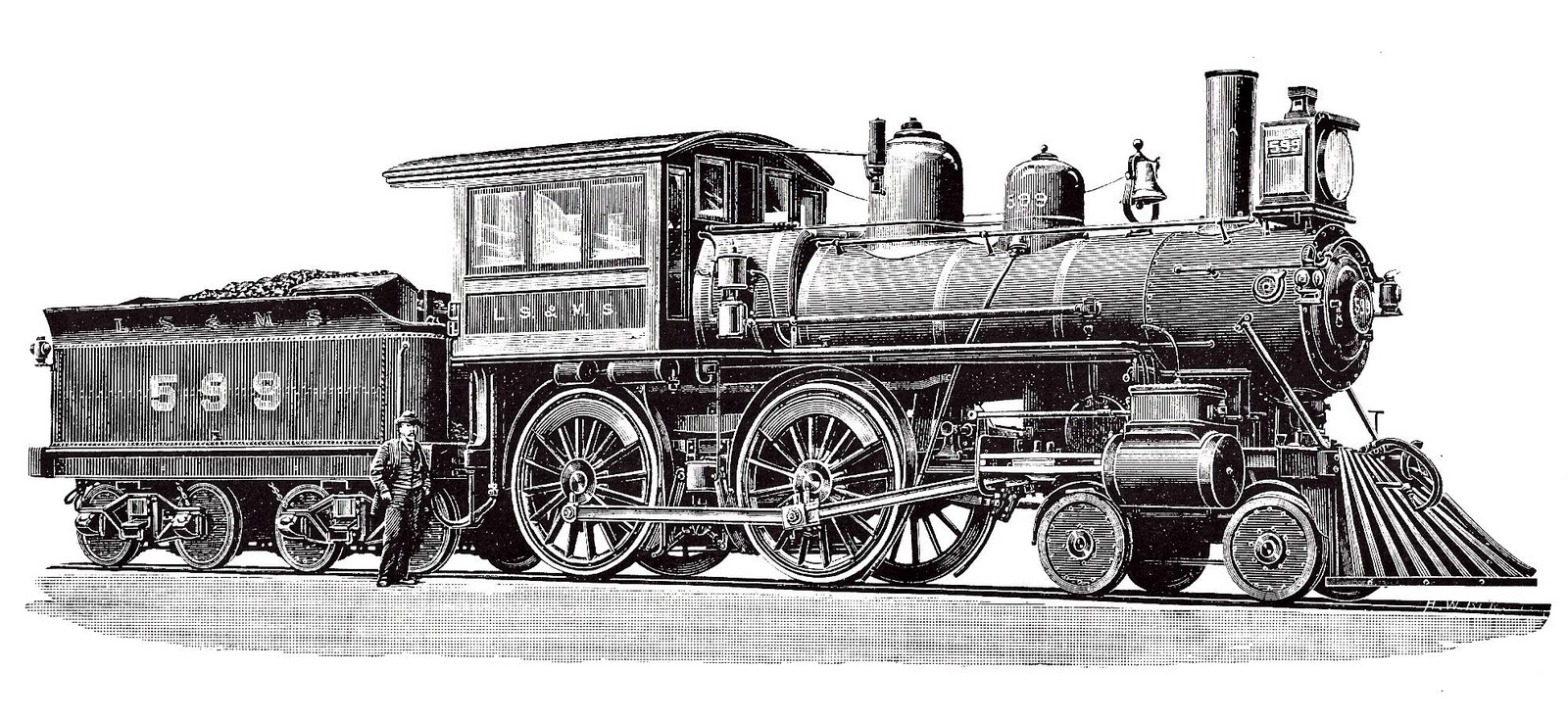

Why does a steam engine look like that? It wasn’t an aesthetic choice. It was a desperate attempt to manage weight and pressure. If you look at a steam engine train side view of a classic 4-6-2 Pacific type, you’re seeing a very specific balance. Those numbers—4-6-2—refer to the wheel arrangement, a system devised by Frederick Methvan Whyte in 1900.

The two small wheels in front? Those are the leading truck. They guide the massive engine into curves so it doesn't just plow straight off the tracks. The six giant wheels in the middle are the drivers. They do the heavy lifting. The two trailing wheels under the cab support the weight of the firebox.

If the firebox gets too big, the engine needs more wheels at the back to keep from crushing the rails. It’s a literal balancing act of steel.

Driving Rods and the Illusion of Complexity

The most hypnotic part of the side view is the motion. Specifically, the Walschaerts valve gear. If you’ve ever watched a steam locomotive start from a dead stop, you’ve seen that frantic, rhythmic sliding of steel bars. It looks like a chaotic metal ballet, but it's actually a mechanical computer.

The rods have to move the valves to let steam into the cylinders at the exact microsecond the piston is ready to push. If the timing is off by a fraction of an inch, the engine doesn't just run poorly—it can tear itself apart. Seeing this from the side is the only way to truly appreciate the "cutoff," which is basically how engineers "shift gears" by changing how long the steam stays in the cylinder.

Why the Side View is the "Hero Shot" for Photographers

Ask any railfan. The "three-quarters" view is fine for catalogs, but the pure side profile is the hero shot. It captures the sheer scale. A Union Pacific "Big Boy," arguably the most famous locomotive in existence, is 132 feet long. You can't grasp that from the front. From the front, it’s just a big black circle with a light. From the side, it’s a city block made of iron.

👉 See also: Why You Probably Need a Computer Camera Cover Slider Right Now

- Scale perception. You see the tender (the coal car) in relation to the engine.

- Mechanical transparency. You can actually see the leaf springs and the brake rigging.

- The Steam Trail. When an engine is working hard, the steam doesn't just go up; it trails back over the length of the boiler, creating a sense of speed that a static photo shouldn't be able to have.

The Evolution of the Silhouette

In the early 1830s, engines like the John Bull looked like tall chimneys on wheels. They were vertical. As we figured out that "fast" meant "low and long," the silhouette stretched out. By the 1930s, we hit the era of streamlining.

Take the Mallard or the Pennsylvania Railroad K4. From the side, these engines were encased in "shrouding." Designers like Raymond Loewy wanted to make trains look like they were moving at 100 mph while they were standing still. They covered the beautiful, messy mechanicals with smooth, bullet-shaped steel. It was gorgeous, sure, but many engineers hated it. It made maintenance a nightmare because you couldn't get to the parts that needed oiling.

Today, most restored engines have had their streamlining removed or were never streamlined to begin with. We want to see the "works." We want the raw steam engine train side view that shows the rivets and the grease.

Misconceptions About What You’re Seeing

People often think the big dome on top of the boiler is where the steam comes out. Sorta. That’s actually the steam dome. Its job is to collect the "driest" steam from the very top of the boiler, far away from the splashing water, so it doesn't wreck the cylinders.

✨ Don't miss: MacBook Pro 16 inch 2024: What Most People Get Wrong About the M4 Max

And that long horizontal pipe running along the side? That’s often the handrail for the crew, but sometimes it’s a delivery pipe for the injectors.

Everything has a purpose. Even the "cowcatcher" at the front (the pilot) is angled specifically to deflect obstacles away from the tracks rather than letting them get sucked under the wheels. Seeing this from the side gives you the best perspective on how that geometry actually works.

How to Capture the Best Steam Engine Train Side View

If you’re out with a camera, don't just stand there and click. Honestly, most people fail because they stand too close. You need a long lens and some distance. This flattens the perspective, making the engine look even more massive and powerful.

- Wait for the "Chuff." The best photos happen right as the engineer opens the throttle. You get a massive plume of white steam from the cylinders (the "cinder" blast) and dark smoke from the stack.

- Check the Light. Side views are brutal in midday sun because the boiler casts a massive shadow over the wheels. Go for "Golden Hour." You want the light hitting the driving rods directly to show off the polished steel.

- Focus on the Drivers. The center of your frame should be the middle driving wheel. It's the visual anchor of the whole machine.

Technical Realities of the 21st Century

Maintaining these machines today is a nightmare of epic proportions. You can't just buy parts for a 1920s locomotive at a hardware store. Everything has to be custom-forged. When you look at the profile of an engine like the Flying Scotsman, you’re looking at millions of dollars in heritage funding and tens of thousands of man-hours.

The boiler alone has to undergo "ultrasound" testing to make sure the steel hasn't thinned out to dangerous levels. If a boiler blows, it’s not a leak; it’s a bomb. This is why many modern "steam" experiences are actually diesel engines hidden inside a steam-shaped shell. But for the purists, the real deal—the one with the pulsing air pumps and the smell of hot oil—is the only thing worth filming.

The Actionable Perspective

If you want to truly appreciate a steam engine train side view, stop looking at pictures and find a "Photo Freight" event. These are specific days where heritage lines run trains specifically for photographers. They’ll do "run-pasts," where the train backs up and then charges forward at full steam just so you can get that perfect profile shot.

Next time you’re at a museum or a siding, walk the length of the engine. Start at the pilot, look at the cylinder cock valves, follow the reach rod back to the cab, and end at the tender. Notice how the rivets change size. Look at the wear on the wheel flanges.

The side view isn't just a picture; it's a biography of a machine that quite literally built the modern world. Without this specific horizontal engineering, we’d still be moving goods by horse and buggy.

Steps for your next visit:

- Identify the wheel arrangement. Use the Whyte notation (count the wheels on one side and double it).

- Locate the air pump. Usually, it's a vibrating, clanking box mounted on the side of the boiler.

- Watch the "leaf springs." See how they compress as the engine moves over a rail joint.

The steam engine is the closest thing to a living creature humans have ever built out of dead metal. Seeing it from the side is like looking at its skeleton and its heart at the same time. Don't just snap a photo. Watch the movement. Listen to the rhythm of the rods. That’s where the real magic is.