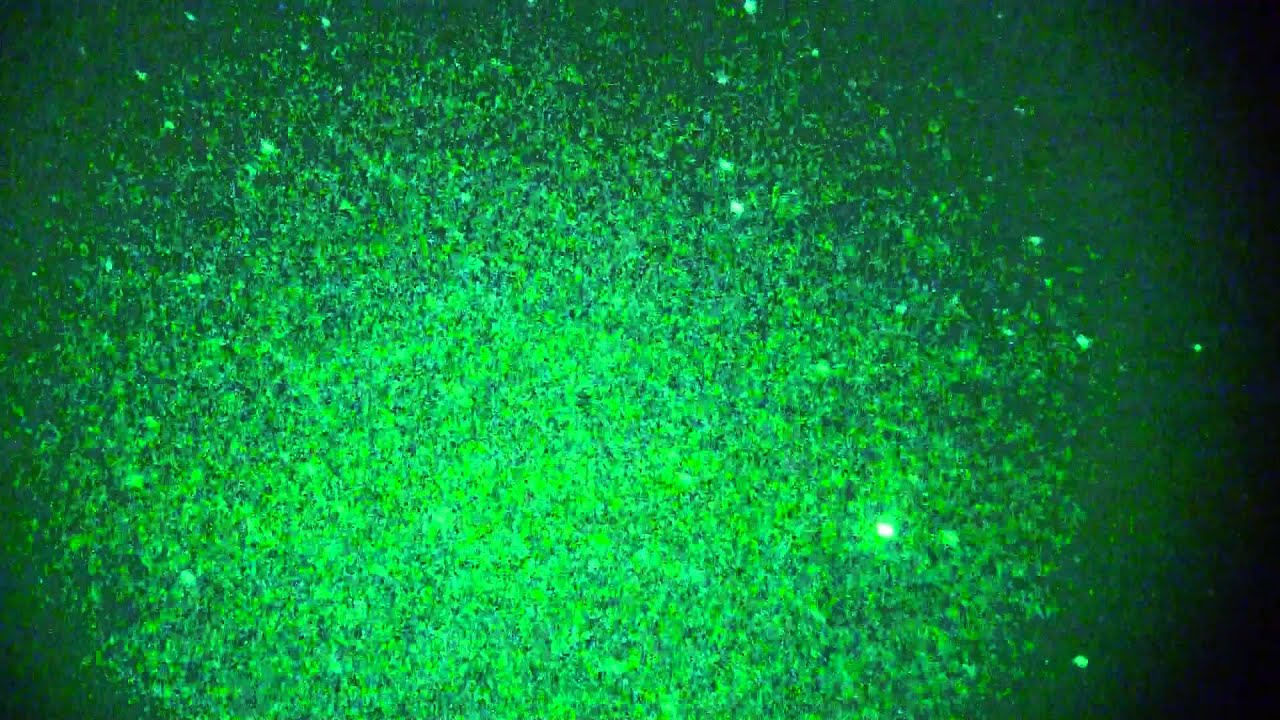

You think you’ve seen the night sky. You go out to a dark-sky park, wait for your eyes to adjust for thirty minutes, and stare up at the Milky Way. It’s beautiful, sure. But honestly? You’re seeing maybe 2,500 to 3,000 stars on a perfect night. That’s a tiny fraction of what’s actually hanging over your head. When you look at stars under night vision, the universe stops being a collection of distant pinpricks and starts looking like a crowded, glowing, chaotic masterpiece.

It’s an absolute game-changer.

The first time I looked through a PVS-14 with a high-spec L3Harris unfilmed white phosphor tube, I actually gasped. It wasn’t just "brighter." It was a complete structural reimagining of the heavens. Dark patches of the sky that looked like empty voids to the naked eye were suddenly teeming with thousands of tiny, sharp lights. The Great Orion Nebula didn't just look like a faint smudge; it looked like a swirling, three-dimensional cloud of gas and dust.

The Physics of Why Stars Under Night Vision Look Different

Human eyes are pretty amazing, but they have a massive limitation: the "integration time" of our biological sensors. We basically see in real-time. Image intensifier tubes (I2), which power most night vision devices, work by converting photons (light) into electrons, amplifying those electrons thousands of times, and then hitting a phosphor screen to turn them back into light.

This process allows us to see light in the near-infrared (NIR) spectrum.

Stars emit a ton of energy in the infrared range. Because night vision devices are specifically tuned to be sensitive to these wavelengths—roughly 700 to 900 nanometers—they pick up stars that are physically invisible to the human eye. We call these "sub-visual" stars. When you’re observing stars under night vision, you aren’t just seeing a magnified view; you are seeing a broader slice of the electromagnetic spectrum.

It’s like being able to hear a dog whistle.

Wait, I should clarify something. There’s a big difference between digital night vision (like what’s in your Ring camera or a cheap $200 "night vision" monocular from Amazon) and analog image intensifiers. Digital sensors are getting better, but they still struggle with the "noise" or graininess when trying to resolve tiny points of light like stars. Analog tubes, specifically Gen 3 gear, provide a much cleaner, more immediate window into the cosmos.

✨ Don't miss: Why the Amazon Kindle HDX Fire Still Has a Cult Following Today

White Phosphor vs. Green Phosphor: Which Wins for Stargazing?

For decades, night vision was synonymous with that "Matrix-style" green glow. This is P43 phosphor. It’s great for high contrast in the woods, but for looking at the sky, a lot of experts—myself included—prefer White Phosphor (P45).

Why? Because it feels more natural.

When you look at stars under night vision using white phosphor, the sky appears in shades of black, gray, and white. This mimics the way our eyes naturally perceive the night sky, making the transition from the device to the naked eye much less jarring. Research in visual ergonomics suggests that white phosphor reduces eye strain during long observation sessions. If you’re spending four hours tracking the Perseid meteor shower, your brain will thank you for the neutral tones.

Scintillation and "The Sparkle"

One thing nobody tells you until you hold the device is that the sky "sparkles" through night vision. This is called scintillation or "EBI" (Equivalent Background Illumination). On a high-quality tube with low EBI, the background of space looks incredibly dark, which makes the stars pop with a crispness that's almost impossible to describe.

Nebula Hunting Without a Giant Telescope

This is the part that usually blows people's minds. Usually, to see deep-space objects like the California Nebula or the North American Nebula, you need a massive telescope and a long-exposure camera.

With night vision? You just need a 6nm or 7nm H-alpha filter.

Because many nebulae are primarily composed of hydrogen gas, they emit light at a specific wavelength (656.3nm). If you put an H-alpha filter on your night vision device, it cuts out all the light pollution and "background" starlight, leaving only the glowing gas of the nebula.

🔗 Read more: Live Weather Map of the World: Why Your Local App Is Often Lying to You

- The Horsehead Nebula: Hard to see even with a 12-inch telescope. With a PVS-14 and an H-alpha filter? It’s right there.

- The Barnard’s Loop: A massive arc of gas in Orion that most people never see. Under night vision, it dominates the constellation.

- The Rosette Nebula: It looks like a ghostly flower blooming in the dark.

It turns the hobby of astronomy from "squinting at fuzzy gray blobs" into "touring the galaxy in high definition."

The Learning Curve: It’s Not Just Point and Shoot

You can’t just walk outside and expect a perfect view. There are some real-world hurdles. First, there's the "halo" effect. Bright stars—like Sirius or Vega—will create a small ring of light around them in the intensifier. This is caused by electrons bouncing off the microchannel plate. If a tube has a large "halo" spec, it can actually obscure smaller stars nearby.

Then there’s the issue of gain.

If you crank the manual gain up too high, the sky becomes "noisy," filled with a snowy electronic haze. You have to find that sweet spot where the stars are bright but the background remains a deep, inky black. It’s a bit of an art form.

Satellites: The Uninvited Guests

Here is a weird fact: when you look at stars under night vision, you will realize just how much "trash" is floating in orbit. On any given night, you’ll see dozens of satellites crossing the field of view.

Most of these are invisible to the naked eye. Through night vision, they look like steady, moving stars. You’ll see them tumble (causing them to flash), you’ll see Starlink "trains" stretching across the horizon, and you’ll even see the International Space Station looking like a freaking spotlight. It’s a sobering reminder of how crowded our immediate neighborhood in space has become.

Real-World Expert Advice for New Observers

If you’re serious about seeing stars under night vision, don't just buy the first thing you see on a tactical website. Most tactical night vision is set to "infinity focus," which is fine for the sky, but you really want a device that allows for fine-tuning.

💡 You might also like: When Were Clocks First Invented: What Most People Get Wrong About Time

- Check your specs. Look for a high Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR). Anything over 30 is good; over 35 is incredible. This ensures the "space" between the stars stays dark.

- Use a tripod. Even though a monocular is handheld, your heartbeat will cause the stars to jitter at higher magnifications. A simple bridge mount and a tripod will make the view rock-steady.

- Light pollution still matters. People say night vision "sees through" light pollution. It doesn't. It amplifies everything. If you are in the middle of Las Vegas, you're just going to amplify the smog and the neon glow. You still need to get away from the city for the best results.

- The "Slow-Scan" technique. Don't just whip the device around. Move it slowly. Let your brain process the layers of depth. You'll start to notice dark nebulae—clouds of dust that block the light from stars behind them—which creates a 3D effect.

Is It Worth the Cost?

Let’s be honest. A good Gen 3 night vision setup is going to cost you between $3,000 and $5,000. That’s a lot of money. You could buy a very nice computerized telescope for that price.

But a telescope gives you a narrow, keyhole view of the universe. Night vision gives you the whole thing at once. It’s the difference between looking at a painting through a straw and standing in the middle of the gallery.

For many amateur astronomers, the "instant gratification" of night vision has revitalized their love for the hobby. There’s no setup time. No cooling down the mirrors. No alignment. You just step outside, turn it on, and the universe opens up.

Actionable Steps for Your First Session

If you’ve managed to get your hands on some gear, here is how you should spend your first night observing stars under night vision:

- Step 1: The Naked Eye Comparison. Look at the Big Dipper. Count the stars you see. Then, bring the night vision to your eye. You’ll likely see three to four times as many stars within the "bowl" of the dipper alone.

- Step 2: Find the Milky Way core. Even if it's low on the horizon, the sheer density of the "star steam" is breathtaking. Look for the "Great Rift," the dark lane of dust that splits the galaxy.

- Step 3: Hunt for Meteors. Because of the increased light sensitivity, you will see "micro-meteors" that are too faint for the human eye. On a normal night, you might see one or two meteors an hour. Under night vision, you might see one every few minutes.

- Step 4: Use a 3x or 5x Magnifier. Most night vision is 1x (no magnification). Adding a screw-on "afocal" lens will turn your device into a high-powered spotting scope for the moon and planets.

The universe is a lot busier than it looks. We spend our lives under a veil of darkness, seeing only the brightest, most obvious lights. Stepping into the world of stars under night vision is like finally turning on the lights in a dark room. You realize you were never alone in the dark; you were just missing the right tools to see the party happening right in front of you.

Get away from the streetlights. Turn off your phone. Look up. There is a whole lot of "hidden" reality waiting for you.

Next Steps for Deep Sky Observation:

Invest in a 1.25-inch eyepiece adapter for your night vision device. This allows you to "prime focus" your PVS-14 to an actual telescope. This combination—known as "Electronically Assisted Astronomy" (EAA)—effectively triples the size of your telescope's aperture, allowing a small 4-inch travel scope to perform like a massive 12-inch observatory grade instrument.