You're staring at a grid of numbers. It looks like a tax form from a nightmare. Rows and columns of four-digit decimals stretching across the page, starting at .0000 and creeping toward .9999. If you’ve ever taken a stats class, you know exactly what I’m talking about. The standard normal distribution table z is that ubiquitous cheat sheet we use to make sense of the bell curve. But here’s the thing: most students—and honestly, plenty of professionals—treat it like a magic spell they don’t quite understand.

It’s just a map. That’s it.

Imagine you're trying to figure out if a test score is actually impressive or just "fine." Or maybe you’re an engineer at a place like Intel checking if a batch of processors is actually within spec. You can’t just look at the raw data. You need a common language. That’s where the z-table comes in. It converts the messy, real-world chaos of heights, weights, or click-through rates into a clean, standardized format where the mean is 0 and the standard deviation is 1.

Why the bell curve is actually a lie (kinda)

Okay, "lie" is a strong word. But the perfect bell curve you see in textbooks? It’s an ideal. It’s the "Platonic form" of data. In the real world, things are crunchy and lopsided. However, the Central Limit Theorem tells us that if we take enough samples, things start to look like that smooth, symmetrical hump. Abraham de Moivre actually stumbled onto this back in the 1730s while trying to help gamblers figure out their odds. He didn't call it the "normal distribution" back then; he was just looking at binomial expansions.

📖 Related: Apple Store in Sherman Oaks: Why the Fashion Square Location Actually Matters

Later, Carl Friedrich Gauss polished the math, which is why we sometimes call it the Gaussian distribution. The standard normal distribution table z is basically the condensed wisdom of these guys put into a format that doesn't require you to solve a terrifying integral involving $e$ and $\pi$ every time you want to calculate a probability.

The formula for the probability density function looks like this:

$$f(x) = \frac{1}{\sigma\sqrt{2\pi}} e^{-\frac{1}{2}\left(\frac{x-\mu}{\sigma}\right)^2}$$

Do you want to solve that manually? No. Nobody does. Not even math professors on their day off. The table is your shortcut. It does the heavy lifting for you by pre-calculating the area under that curve.

Reading the grid without losing your mind

When you look at a standard normal distribution table z, you’re usually looking at "cumulative from the left." This is a huge point of confusion. If you look up a z-score of 1.0, and the table gives you 0.8413, that doesn't mean "10% of people." It means 84.13% of the data falls below that point.

Think of it like a progress bar. At a z-score of 0 (the exact middle), your progress bar is at 50%.

To find a value, you look at the left-hand column for the first decimal (like 1.9) and the top row for the second decimal (like .06). Where they meet—1.96—is a famous number in statistics. It’s the threshold for the 95% confidence interval (technically, it leaves 2.5% in each tail).

- Positive z-scores: You're above average. Congrats.

- Negative z-scores: You're below the mean.

- Zero: You are the definition of average.

One thing people forget is that there are different types of tables. Some show the area from the mean to z. Others show the "tail" area. If your table starts at 0.0000 for a z-score of 0, you’re looking at a "mean-to-z" table. If it starts at 0.5000, it’s a cumulative table. Always check the little shaded diagram at the top of the page. It’s the legend for your map.

Real-world stakes: It’s not just for homework

Why does this matter outside of a classroom? Quality control.

Let's say you're a data scientist at a major logistics firm. You’re monitoring delivery times. If the mean delivery time is 30 minutes with a standard deviation of 5 minutes, and a driver takes 45 minutes, what’s their z-score?

$(45 - 30) / 5 = 3$.

A z-score of 3.0.

🔗 Read more: Are the new iPhones waterproof? What most people get wrong

Looking that up in the standard normal distribution table z, you’ll see that a z-score of 3.0 accounts for about 99.87% of all outcomes. That driver isn't just "late." They are in the 0.13% of slowest deliveries. That’s an outlier. That’s a signal that something went wrong—a flat tire, a closed bridge, or maybe a very long lunch break.

The medical field uses this constantly for BMI, blood pressure, and bone density. If a doctor tells you your bone density has a T-score (which is just a version of a z-score) of -2.5, they are using the standard normal distribution to tell you that you're significantly below the healthy average. They aren't guessing; they are comparing you to a standardized population.

The 68-95-99.7 Rule: The cheat code

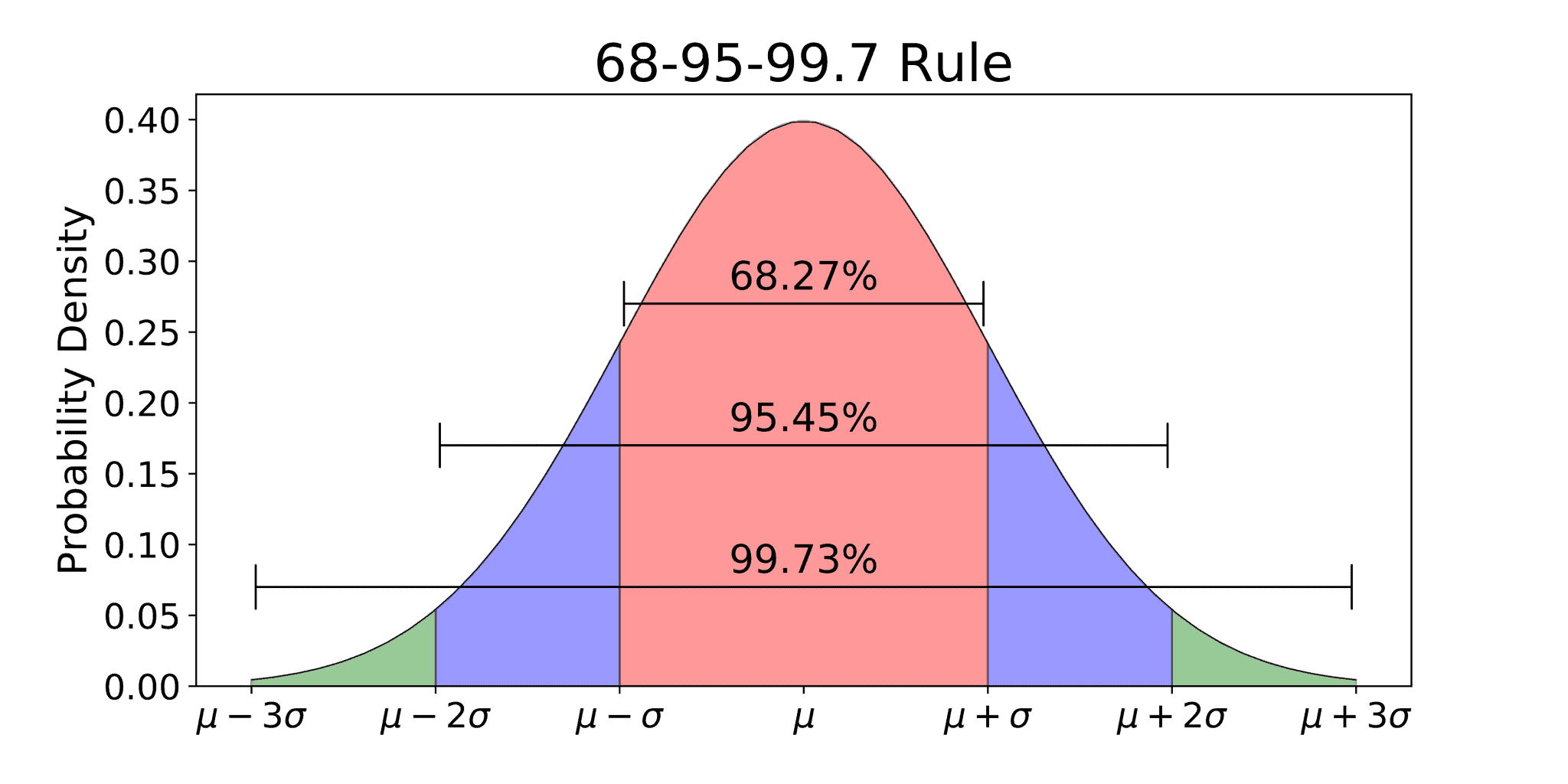

If you don't have a standard normal distribution table z handy, you can use the Empirical Rule. It’s a rough-and-ready way to visualize where data lives.

Roughly 68% of everything falls within one standard deviation of the mean.

Jump out to two standard deviations, and you’ve captured 95%.

Three standard deviations? You’re at 99.7%.

This is why "Six Sigma" in manufacturing is such a big deal. It’s aiming for a process where the "defects" only happen once you get six standard deviations away from the mean. We’re talking 3.4 defects per million opportunities. It’s an obsession with the extreme tails of the z-table.

Common traps and how to escape them

The biggest mistake? Forgetting symmetry.

Most tables only show positive z-scores because the curve is a mirror image. If you need to find the area for a z-score of -1.5, but your table only has positives, you just find 1.5 and do some mental gymnastics. If the area for +1.5 is 0.9332 (cumulative), then the area above it is 1 - 0.9332 = 0.0668. Because the curve is symmetrical, the area below -1.5 is also exactly 0.0668.

Don't let the negative signs scare you. They just tell you which side of the mountain you're standing on.

Another trap is the "between" problem. If you want to know how many people score between a z of 0.5 and 1.5, you can't just look up one number. You have to find the area for 1.5, find the area for 0.5, and subtract the smaller from the larger. You're basically taking a big slice of pie and cutting off the end you don't want.

👉 See also: Farting on infrared camera: Why those viral videos are almost always fake

Is the z-table becoming obsolete?

Sorta. In the age of Python, R, and even advanced Excel functions like =NORM.S.DIST(), nobody is actually carrying around a physical paper table in their pocket. But understanding how the standard normal distribution table z works is like learning to do long division before using a calculator. It builds the "statistical intuition" you need to spot when a computer output is hallucinating or when your data is skewed.

If your data isn't normally distributed—if it's "fat-tailed" like stock market crashes or "skewed" like wealth distribution—the z-table will lie to you. It will make extreme events seem much more impossible than they actually are. Nassim Taleb has written extensively about this in The Black Swan. He argues that relying too heavily on Gaussian models (and by extension, the z-table) is what leads to financial collapses because the real world has more "outliers" than the table suggests.

Step-by-step: Using the table for a real problem

Let’s walk through a real scenario. You’re hiring for a role that requires a high level of spatial reasoning. You give 500 applicants a test. The mean score is 70, and the standard deviation is 10. You only want to interview the top 10%.

- Identify the goal: You need the "cutoff" score.

- Work backward: Since you want the top 10%, you're looking for the point where 90% of people are below you.

- Scan the table: Look inside the grid of the standard normal distribution table z for the value closest to 0.9000.

- Find the z-score: You’ll find 0.8997 at a z-score of 1.28.

- Convert back to reality: Use the formula $X = \mu + Z\sigma$.

$X = 70 + (1.28 \times 10) = 82.8$.

Anyone who scored 83 or higher gets an interview. Simple. No guesswork.

Actionable insights for your next data project

If you're working with data today, don't just plug numbers into a software package. Do these three things to master the distribution:

- Visualize first: Always plot a histogram of your data before reaching for the z-table. If it looks like two humps (bimodal) or a giant slide (skewed), the z-table's probabilities will be wrong.

- Check your tails: If you are dealing with risk (like insurance or finance), remember that the "tails" in the real world are often "thicker" than the standard normal distribution predicts. Add a safety margin.

- Standardize manually once: Take a small dataset, calculate the mean and standard deviation, and convert each point to a z-score yourself. Once you feel the "distance from the mean" in your bones, the table stops being a grid of numbers and starts being a 3D visualization of probability.

Stop treating the table as a hurdle to clear for an exam. Use it as a lens to see how "extreme" or "normal" the world around you actually is.