You’re sitting in a quiet room, maybe looking at a tree outside your window or just staring at the grain of a wooden desk, and you start to wonder if there’s more to it. Not just "more" in a scientific, atoms-and-quarks kind of way, but a deeper resonance. This isn't a new feeling. In 1259, a man named Giovanni di Fidanza—better known to history as St. Bonaventure—climbed Mount Alverna, the same place where Francis of Assisi reportedly received the stigmata. He wasn't looking for a view. He was looking for a way to bridge the gap between human logic and the divine. What he wrote there, the Journey of the Mind into God (or Itinerarium Mentis in Deum), became one of the most influential spiritual maps in Western history.

It’s a short book. You can read it in an afternoon. But honestly? It’s dense as a lead brick if you don't know the "why" behind it. Bonaventure wasn't just writing a theology textbook; he was writing a travel guide for the soul.

Why the Itinerarium is More Than Just Old Philosophy

Most people assume medieval philosophy is just a bunch of guys arguing about how many angels can dance on the head of a pin. That’s a total myth, by the way. Bonaventure was a high-level intellectual, a contemporary of Thomas Aquinas at the University of Paris. But while Aquinas was busy building a massive, logical "Summa" of everything, Bonaventure was interested in the experience of the divine. He believed that the mind doesn't just "find" God through cold logic. It travels there.

The Journey of the Mind into God is structured around six stages of illumination. Think of them like rungs on a ladder. Or better yet, think of them as different lenses for a telescope. You start by looking at the dirt under your fingernails and end by staring into the blinding light of the infinite. It’s a progression from the outside world, to the inside of your own head, and finally above yourself.

The World as a Mirror

The first step is basically about paying attention. Bonaventure argues that the physical world is a "vestige" or a footprint of the divine. If you look at a painting, you see the brushstrokes of the artist. If you look at a sunset, or a complex ecosystem, or even the way gravity holds things together, you’re seeing the "trace" of a creator.

He’s very specific here. He doesn't want you to just think "nature is pretty." He wants you to see the power, wisdom, and goodness reflected in the sheer existence of things. It’s a bit like modern mindfulness, but with a theological endgame. You aren't just being "present"; you're being a detective looking for clues of the infinite in the finite.

💡 You might also like: Finding the most affordable way to live when everything feels too expensive

Then comes the second stage: how we actually perceive this stuff. Bonaventure gets into the nitty-gritty of the five senses. He thinks it's wild that our minds can take in a physical object—like a red apple—and turn it into a mental concept. To him, the fact that our senses can interface with the world is a miracle in itself. It shows a harmony between the "out there" and the "in here."

Looking in the Mirror: The Mind Itself

Once you’ve looked at the world, Bonaventure tells you to turn the camera around. Look at yourself. This is where the Journey of the Mind into God gets really interesting for people who like psychology.

In stages three and four, he looks at the "natural" powers of the mind:

- Memory: Our ability to hold the past, present, and future at once.

- Intellect: Our ability to understand universal truths (like 2+2=4).

- Will: Our ability to choose and love.

He argues that because we can think about "eternity" or "perfection"—even though we’ve never seen a perfect thing in our lives—that idea had to come from somewhere. It’s the "signature" of the divine on the human soul. He calls the soul an "image" of God, not just a footprint. It’s a higher resolution reflection.

But there’s a catch. Bonaventure is a realist. He knows humans are messy, distracted, and often kind of awful to each other. He says our "mirror" is cracked and dusty. We can't see the reflection clearly because we're too obsessed with our own egos or material cravings. This is where he brings in the need for grace—specifically through Christ—to "clean the lens." Whether you're religious or not, the metaphor holds up: you can't see truth if your mind is cluttered with junk.

📖 Related: Executive desk with drawers: Why your home office setup is probably failing you

The Final Ascent into the Cloud

The last two stages (five and six) move from the human soul to God’s actual nature. He focuses on two main "names" for the divine: Being and Goodness.

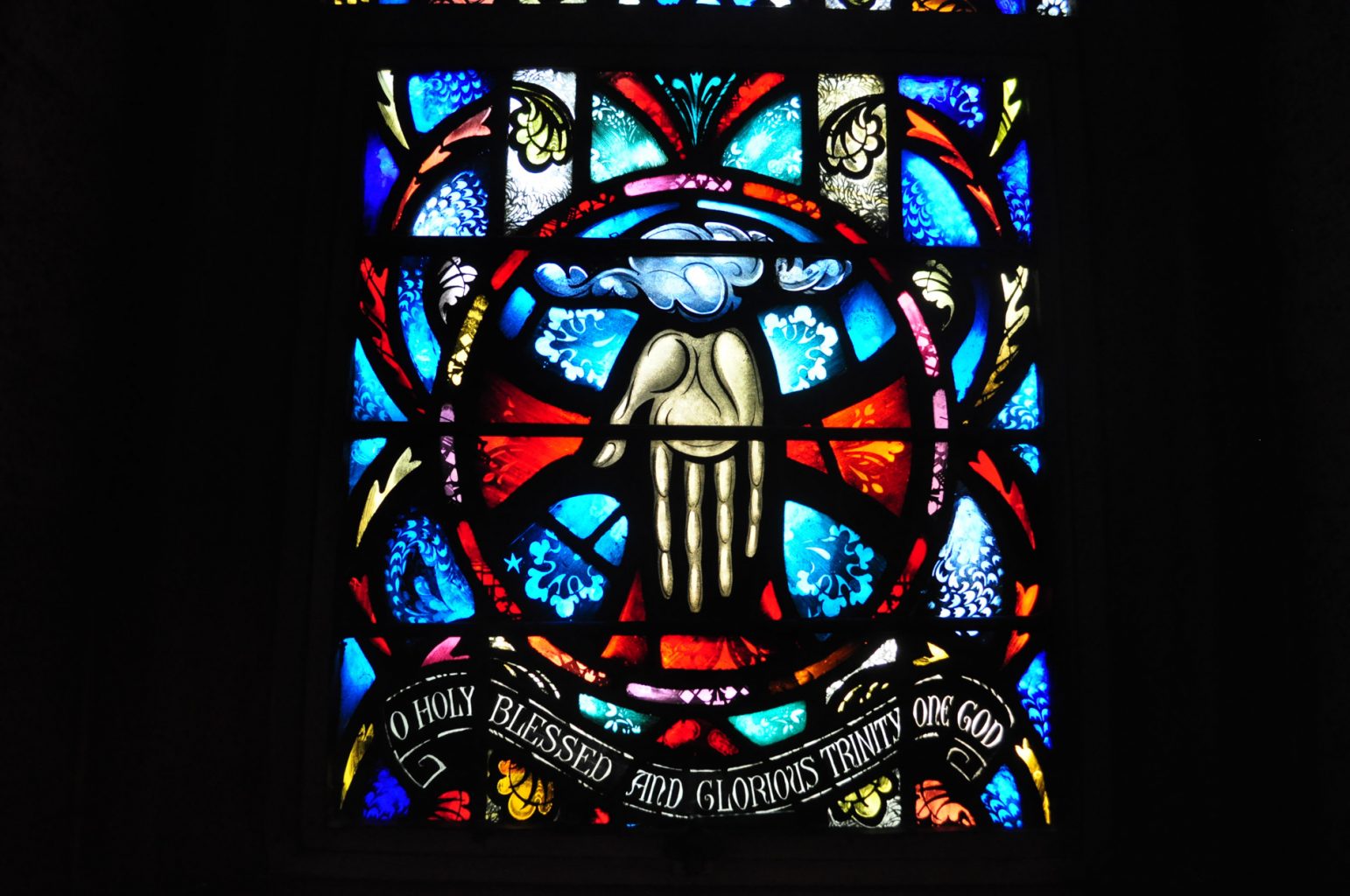

Stage five is about God as "Being" (the I Am). It’s very abstract. It’s about the sheer fact that anything exists at all instead of nothing. Stage six is about "Goodness" and the Trinity. For Bonaventure, God isn't a static, lonely block of power. God is a fountain of love that is constantly overflowing.

But here’s the kicker. After all this intellectual heavy lifting—all this logic and philosophy—Bonaventure basically tells you to throw it all away in the final chapter.

He calls it "mystical death."

He says that if you want to actually reach the destination of the Journey of the Mind into God, you have to stop thinking. Your intellect can only take you so far. At some point, you have to stop analyzing the map and start walking. He describes a state of "ecstasy" where the mind is left behind and only "affection" or love remains.

👉 See also: Monroe Central High School Ohio: What Local Families Actually Need to Know

"Ask for grace, not instruction; desire, not intellect; the groaning of prayer, not the diligent reading," he writes. It’s a surprisingly humble ending for a guy who was one of the smartest people in Europe.

Common Misconceptions

People often get Bonaventure wrong by thinking he was anti-science or anti-reason. He wasn't. He loved reason. He just thought reason had a ceiling.

Another big mistake is thinking this journey is a solo mission. In his view, you can't do this without help—what he calls "divine illumination." It’s not like a gym workout where you just grind until you’re enlightened. It’s more like opening a window to let the light in. You do the work of walking to the window, but you don't create the sun.

How to Apply This Today (The Actionable Part)

You don't have to be a 13th-century monk to get something out of this. The Journey of the Mind into God offers a framework for living with more depth.

- Practice "Vestigial" Seeing: Next time you’re outside, don't just "see" a tree. Look at its complexity—the way it turns light into food, its structural integrity. Try to see it as a "footprint" of something larger. It shifts your perspective from consumer to observer.

- Audit Your Mental Mirror: Bonaventure talked about the "dust" on the soul. What’s your dust? Is it social media envy? Constant noise? Spend ten minutes a day in actual silence. No podcasts, no music. Just see what’s going on in your "memory, intellect, and will."

- Acknowledge the Ceiling: Recognize that logic and data can’t explain everything. Science tells us "how," but it’s terrible at "why." Give yourself permission to value intuition and "affection" (love/connection) as much as you value facts and figures.

- Read the Source: If you’re feeling ambitious, grab a translation of the Itinerarium. Look for the Ewert Cousins translation; it’s widely considered the gold standard for being readable without losing the technical nuance.

Bonaventure’s big point was that we are "itinerants"—travelers. We aren't meant to be stationary. Whether you're looking for God, or just looking for a way to feel less disconnected from the world, the journey starts exactly where you are sitting right now. Just look at the "traces" around you.

The path is open. All you have to do is start walking.