You’ve probably been there. That gut-punch moment where life asks you to do something that feels totally wrong, but your heart—or maybe something even deeper—tells you it’s the only way forward. It’s that agonizing space between what society calls "reasonable" and what you know is your truth. This is exactly where Søren Kierkegaard lives. In 1843, writing under the weirdly theatrical pseudonym Johannes de silentio (John of the Silence), Kierkegaard dropped Fear and Trembling. It wasn’t just a book. It was a psychological grenade.

He didn't write it for the ivory tower academics. Honestly, he wrote it because he was spiraling after breaking off his engagement to Regine Olsen. He was trying to figure out if he was a monster or if he was following a higher calling. To do that, he obsessed over one of the most disturbing stories in the Bible: Abraham and the sacrifice of Isaac. It’s a story about a father taking a knife to his son because God said so. Most people read it and think, "Okay, God was just testing him." Kierkegaard reads it and screams, "Do you have any idea how terrifying this actually is?"

The Absolute Paradox of Fear and Trembling

Kierkegaard is the father of existentialism, but he doesn't feel like a dusty philosopher. He feels like a guy pacing in a candlelit room at 3:00 AM. He introduces this idea of the "Knight of Faith." Most of us try to be the "Tragic Hero." The Tragic Hero is someone like Agamemnon, who sacrifices his daughter for the sake of his people. It’s sad, sure, but the community gets it. There's a moral logic to it. Everyone can cry together and say, "He did it for the greater good."

Abraham is different.

There is no "greater good" in killing your only son. If Abraham tells his neighbors what he’s doing, they don’t call him a hero. They call the police. Or the 19th-century equivalent. This is what Kierkegaard calls the teleological suspension of the ethical. It’s a fancy way of saying that sometimes, the individual's relationship with the Divine (or their deepest personal truth) overrides the general rules of society. It’s a lonely, vibrating state of being. You can't explain it to anyone. If you try, you sound like a lunatic.

That’s the "trembling" part. It’s not a cozy religious feeling. It’s a "shaking in your boots because you might be totally wrong" feeling.

💡 You might also like: Wire brush for cleaning: What most people get wrong about choosing the right bristles

Why We Get the "Leap of Faith" Wrong

Everyone uses the phrase "leap of faith" like it’s a Nike slogan. Just do it! Go for it! But in Fear and Trembling, it’s more like a "plunge into the abyss."

Kierkegaard describes the Knight of Faith as someone who looks completely ordinary. You might see him walking down the street, buying groceries, or tending his garden. He doesn't look like a monk. He doesn't have a glow around his head. He has given up everything—resigned himself to the loss of everything he loves—and yet, he believes he will get it all back in this life, by virtue of the absurd.

Think about that.

Abraham isn't just a guy who is willing to lose Isaac. He is a guy who truly believes he will get Isaac back, even as he raises the knife. He lives in the tension of the impossible. This isn't blind optimism. It’s a radical, terrifying kind of hope that exists only after you’ve looked death in the face and said, "Okay."

The Anxiety of Being an Individual

Kierkegaard hated the "system." At the time, Hegel was the big shot in philosophy, trying to explain everything through logic and history. Kierkegaard thought that was garbage. He felt that logic misses the most important part of being human: the individual's choice.

📖 Related: Images of Thanksgiving Holiday: What Most People Get Wrong

In Fear and Trembling, he argues that being a true individual is a burden. Most people hide in the "crowd." It’s easy to be what your parents, your church, or your TikTok feed tells you to be. There’s no anxiety there because you aren't making the decisions. You’re just following the script.

But the moment you step out and say, "I have to do this thing that no one understands," you are alone. You are in "fear and trembling." This is why the book remains so relevant in 2026. We live in an era of hyper-conformity masquerading as "curated" individuality. We’re all terrified of being cancelled or misunderstood. Kierkegaard says: Being misunderstood is the price of having a soul.

Real-World Nuance: Is This Just a License to Be a Zealot?

Here’s where it gets tricky. Critics often point out that Kierkegaard’s logic could be used by anyone to justify anything. "God told me to do it" has been the excuse for a lot of horror in human history.

Kierkegaard knew this. He wasn't stupid.

He emphasizes that the Knight of Faith is in a state of constant, agonizing self-reflection. It’s not a "get out of jail free" card for morality. It’s an internal struggle that never ends. The difference between a madman and a Knight of Faith is invisible to the outside world. That’s the point. It’s a private relationship. If you’re using Kierkegaard to justify hurting people for your own gain, you’ve missed the "trembling" part. You’re probably just a narcissist.

👉 See also: Why Everyone Is Still Obsessing Over Maybelline SuperStay Skin Tint

Practical Insights for the Modern Existentialist

So, what do you actually do with this? You aren't (hopefully) being asked to sacrifice a child on an altar. But you are likely facing choices that feel heavy, nonsensical, or isolating.

- Acknowledge the silence. You don't have to explain your deepest "why" to everyone. Some things are lost in translation the moment they leave your mouth. It’s okay to have a private truth.

- Differentiate between the Ethical and the Divine. Sometimes, doing the "right" thing according to the rulebook is actually a way of hiding from what you know you’re supposed to do.

- Embrace the Absurd. You don't need a five-year plan that makes sense on a spreadsheet. Sometimes the best moves are the ones that look like failures to everyone else.

- Check your "Trembling." If you aren't at least a little bit scared that you might be wrong, you aren't acting in faith. You’re acting in certainty. And certainty is the death of the spirit.

Kierkegaard eventually died young, collapsed in the street, exhausted by his own mind. He never got Regine back. He never found "peace" in the way we think of it today—yoga retreats and mindfulness apps. He found a different kind of peace: the peace of someone who refused to let the world turn him into a machine.

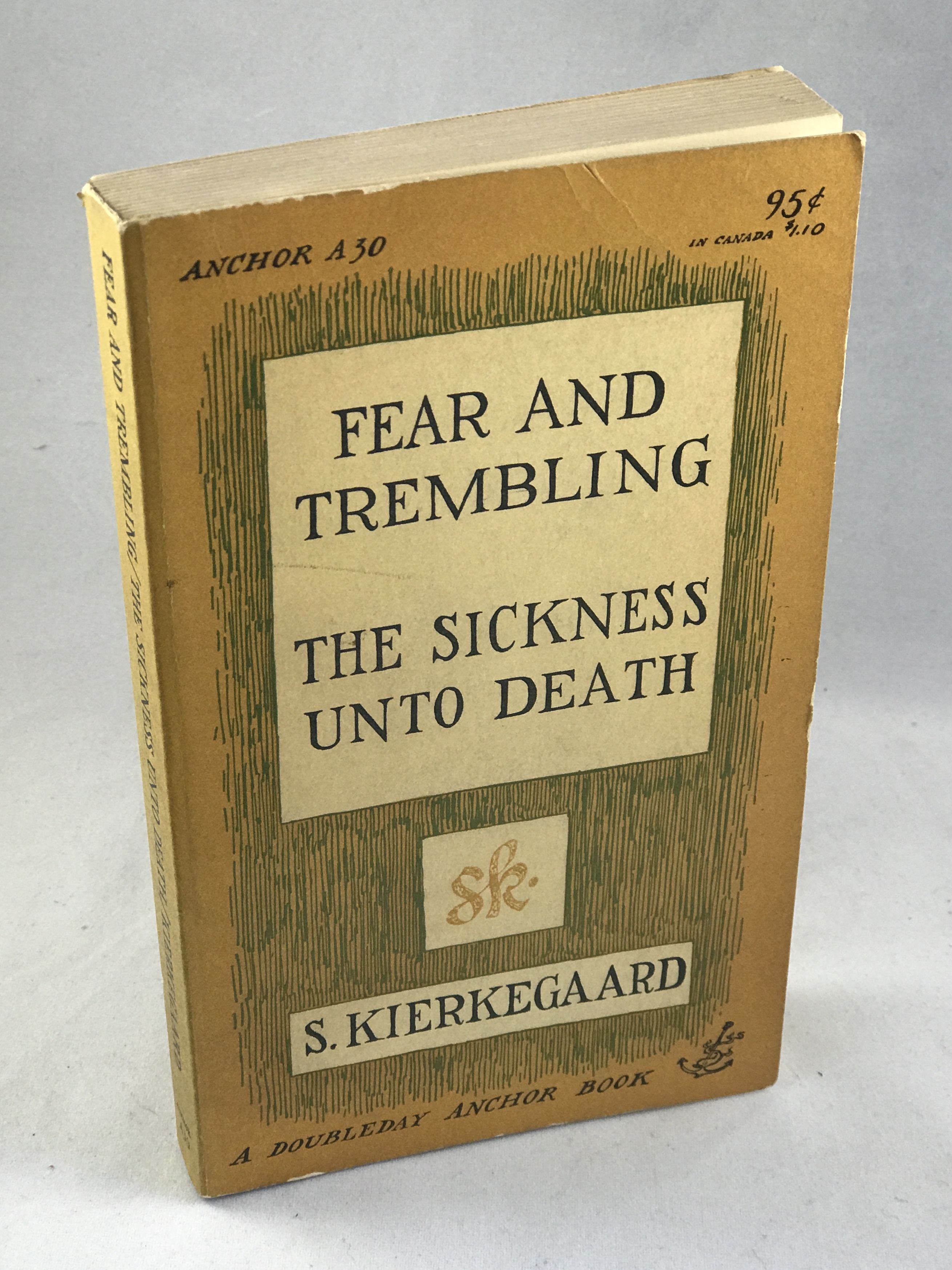

If you want to dive deeper into this, don't just read a summary. Pick up the Penguin Classics version of Fear and Trembling (translated by Alastair Hannay is usually the go-to). Skip the introduction and just start with the "Preamble from the Heart." Read it like a letter from a friend who is losing his mind but might be the only one seeing clearly.

The next time you feel that weird, heavy pressure in your chest when making a big life decision, don't just try to "calm down." Recognize it for what it is. It’s the trembling. It means you’re finally starting to wake up.