Ever walked into a room and smelled something... off? Like something is cooking, but the stove is stone cold? That’s usually the first sign. Most people think spontaneous combustion is some weird paranormal trick or a plot point from a Charles Dickens novel where a character poofs out of existence. Honestly, it’s much more boring and way more terrifying than that. It’s pure chemistry. No ghosts. No lightning bolts. Just a bunch of molecules getting way too excited in a small space until they decide to reset the thermostat to "inferno."

Basically, we're talking about a fire that starts without an external spark. No match. No lighter. No cigarette butt. It just happens.

If you’ve ever left a pile of oily rags in a corner or lived near a massive compost heap, you’ve been closer to this phenomenon than you might realize. It's a slow-motion disaster that suddenly speeds up. One minute you have a damp pile of hay; the next, the barn is a torch. Understanding the meaning of spontaneous combustion isn't just for fire investigators; it's a safety essential for anyone who owns a garage, a farm, or even a fancy kitchen.

The Chemistry of Why Stuff Explodes Solo

Heat is the culprit. But specifically, it’s internal heat.

In a normal fire, you provide the energy. You strike a match. That heat breaks the chemical bonds in the fuel, and the fire takes off. With spontaneous combustion, the material provides its own heat through oxidation or fermentation. Oxidation is just a fancy way of saying "reacting with oxygen." Think of it like rust, but way faster and much, much hotter.

When certain materials—like linseed oil or coal—react with the air, they release a tiny bit of heat. Usually, that heat just drifts away. No big deal. But if the material is packed tight, that heat gets trapped. The temperature rises. Because it's hotter, the chemical reaction happens even faster. Which creates even more heat. It’s a runaway train. Scientists call this "thermal runaway."

Eventually, the material hits its "autoignition temperature." That is the magic number where the substance decides it doesn't need your help to burn. It just ignites. Boom.

💡 You might also like: iPad mini Price: What You’ll Actually Pay in 2026

The Infamous Oily Rag Scenario

This is the classic example that fire departments see every year. Let’s say you’re refinishing a coffee table. You use a rag soaked in linseed oil or tung oil. You finish the job, feel good, and toss the crumpled rag into a plastic bin or leave it in a pile on the workbench.

Bad move.

Linseed oil dries through oxidation. It’s not "evaporating" like water; it’s chemically changing. This process creates heat. In a thin layer on a table, that heat vanishes into the room. In a crumpled pile? The heat stays in the center of the rag. The cotton is a great insulator. The middle of that pile can reach several hundred degrees while the outside feels just warm. Once it hits that flashpoint, the whole garage is at risk. This isn't a myth. It’s a leading cause of house fires during home renovations.

Spontaneous Combustion in the Natural World

It's not just man-made oils. Nature is surprisingly flammable.

Farmers have known about the meaning of spontaneous combustion for centuries, even if they didn't have the chemistry textbooks to explain it. Hay is the big one. If hay is baled while it’s still too wet—usually over 20% moisture—microbes and mold start to have a party. They eat the organic matter and, like any living thing, they generate metabolic heat.

- Microbes raise the temp to about 150°F (65°C).

- At this point, the "good" bugs die, but chemical oxidation takes over.

- The heat continues to climb.

- If the hay stack is big enough to insulate the core, it hits the ignition point.

It's a bizarre sight. A haystack can be smoking from the inside out for days before it finally erupts.

Coal and Compost

Coal mines are another danger zone. Coal is porous. It loves oxygen. When a new face of coal is exposed to air, it starts to oxidize immediately. If the ventilation isn't perfect, that heat builds up in the dust and the debris. Huge coal piles in shipping ports actually have to be monitored with thermal cameras to make sure they aren't about to melt down.

Compost is the same story. That "steam" you see coming off a big mulch pile in the winter? That’s the process in action. If a commercial mulch pile gets too big—usually over 15 feet tall—the pressure and the microbial activity can get so intense that the bottom of the pile starts to char.

✨ Don't miss: Sony Headphones Noise Cancellation: What Most People Get Wrong

The Myth of the Human Torch

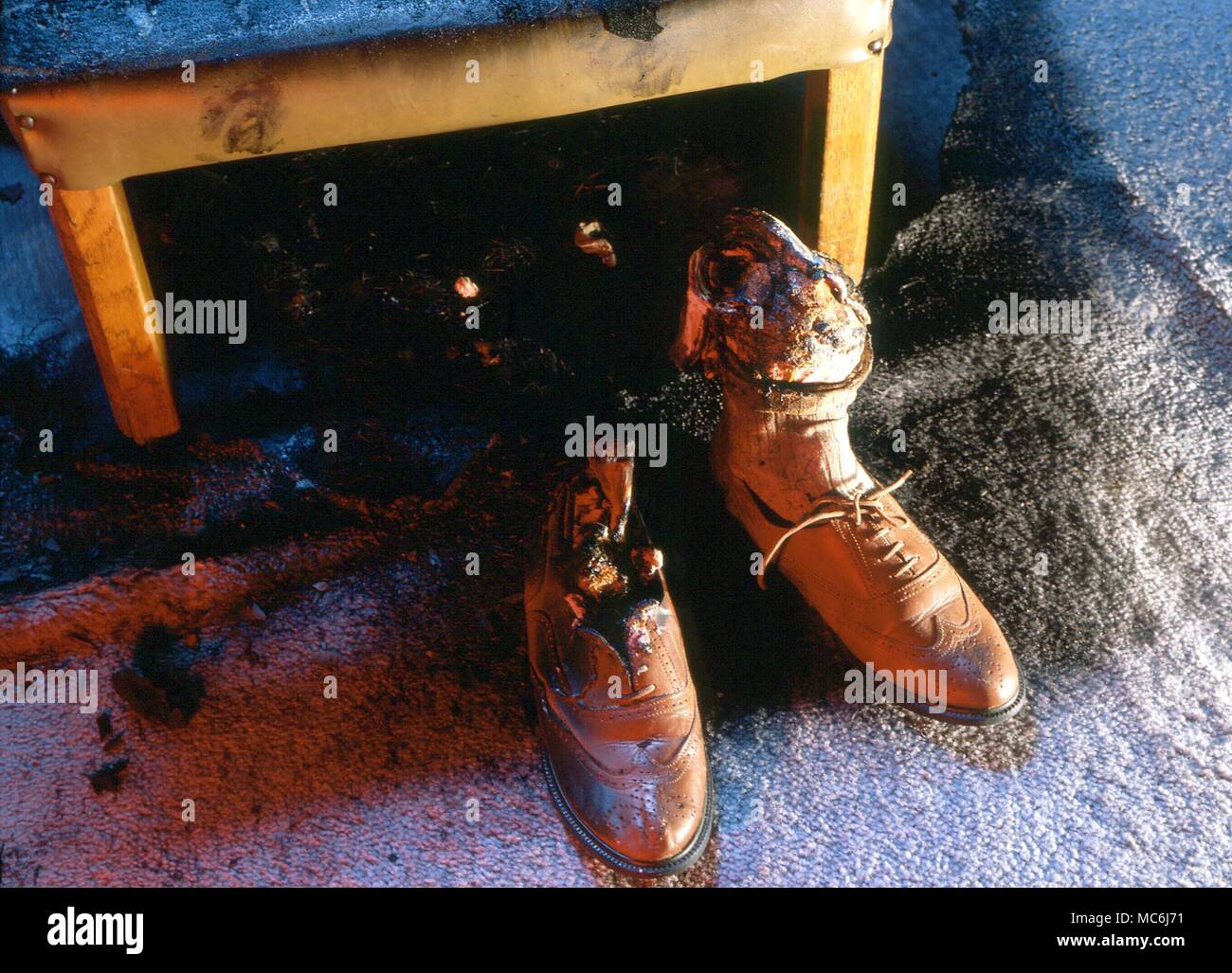

We have to talk about it: Spontaneous Human Combustion (SHC).

You’ve probably seen the grainy photos from the mid-20th century. An old person, usually alone, found burned to a crisp in their armchair, but the rest of the room is totally fine. Maybe their legs are still intact, but the torso is gone. For a long time, people thought this was some mysterious internal "fire from the soul" or a strange chemical reaction in the gut.

Modern forensic science has a much more grounded (and slightly grim) explanation called the "Wick Effect."

Basically, the person isn't spontaneously combusting. There is almost always an external source—a dropped cigarette, a nearby candle, or a heater. The person passes out or dies of a heart attack first. Their clothes catch fire. The fire burns through the skin and begins to melt the subcutaneous fat. The clothing acts like a candle wick, and the body fat acts like the wax. It creates a slow, localized, incredibly hot fire that can burn for hours.

This explains why the rest of the room doesn't burn. It’s not a massive explosion of flame; it’s a slow, steady melt. It’s rare, but it’s definitely not "spontaneous" in the way the chemical reactions in a pile of oily rags are.

Spotting the Signs Before the Spark

How do you know if something is about to go up?

- The Smell: A sweet, sickly, or "fermenting" odor is a huge red flag in hay or mulch. In rags, it smells like hot oil or plastic.

- The Smoke: Often, you won't see flames first. You'll see a thin, wispy blue or grey smoke that seems to be coming out of the center of a pile.

- Discoloration: If you dig into a pile of wood chips or hay and see dark, charred-looking material near the center, it’s already started.

- Heat: If a container feels hot to the touch for no reason, don't open it. Opening it introduces a sudden rush of oxygen that can cause a "backdraft" effect.

Real World Examples and Case Studies

In 2011, a massive fire at a recycling plant in England was traced back to a pile of damp cardboard and plastic. The moisture triggered microbial growth, which led to a thermal runaway. It took days to put out because the fire was "deep-seated." You can't just spray water on the outside; you have to pull the whole pile apart, which, ironically, gives the fire the oxygen it wants.

📖 Related: Who Discovered the Element Plutonium: What Really Happened in Room 307

Then there’s the case of the "Fireproof" safes. Sometimes, the insulation inside old safes can degrade and, in very specific humidity conditions, react with the metal casing. While extremely rare, there have been reports of industrial-grade storage units heating up internally due to chemical decomposition of the packing materials.

Why Particle Size Matters

The meaning of spontaneous combustion changes depending on how small the pieces are. Dust is much more dangerous than a solid block. A big chunk of iron won't spontaneously combust. But "pyrophoric" iron—iron ground into an incredibly fine powder—will catch fire the second it touches the air. This is because the surface area is so high that the oxidation happens all at once.

How to Not Burn Your House Down

If you're doing DIY work or running a business, prevention is surprisingly simple.

- Spread it out: If you have oily rags, don't pile them. Hang them up individually on a clothesline or the edge of a metal bucket outside. Once the oil is completely dry and the rag is "stiff," the danger is gone.

- The Water Bucket: A lot of pros keep a metal can filled with water and detergent. They drop the rags in there. This cuts off the oxygen and keeps the temperature low.

- Proper Storage: For industrial materials, use UL-listed oily waste cans. They have self-closing lids that stay shut to starve any potential fire of oxygen.

- Check Your Attic: Old newspapers or insulation that gets damp can occasionally start the microbial heating process. Keep things dry and ventilated.

Actionable Steps for Safety

Most people will never see a spontaneous fire in their lifetime. But if you do, it's usually because of a simple mistake in the garage or kitchen.

Immediately: Go check your garage or utility closet. If you have a pile of rags from that last staining project, get them out of there. Spread them out on the driveway or a concrete floor away from the house until they are bone dry.

For Gardeners: If you have a large compost pile, keep it turned. Aeration doesn't just help the compost break down faster; it prevents heat from building up in the "dead zones" of the pile.

For Homeowners: Check your smoke detectors. Since these fires often start in "low-traffic" areas like basements or sheds, you might not smell the smoke until it’s too late. A smart smoke detector in the garage is a cheap insurance policy against the weird, slow-burn chemistry of spontaneous combustion.

The "meaning" here isn't just a definition. It's a reminder that chemistry doesn't care if you're watching. It happens in the dark, in the corners, and in the piles we forget to clean up. Stay tidy, keep things dry, and give your chemicals plenty of breathing room.