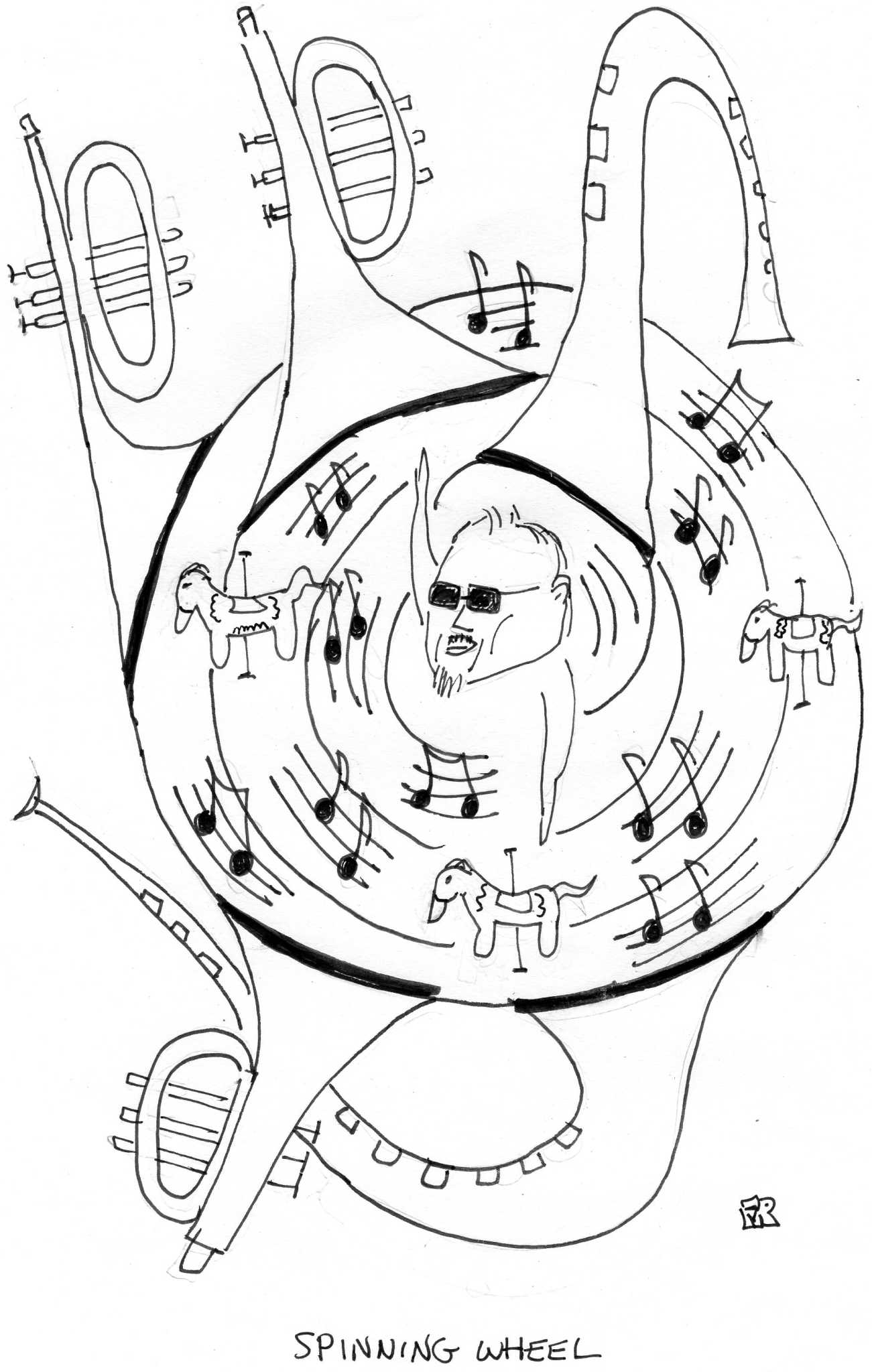

David Clayton-Thomas has a voice that sounds like it was cured in a smokehouse and then dragged over a gravel pit. It’s heavy. It’s soulful. When he bellows "What goes up, must come down," he isn’t just singing a lyric about gravity; he’s delivering a prophecy. Released in 1969, Spinning Wheel by Blood, Sweat & Tears became one of those ubiquitous radio staples that somehow managed to be avant-garde and incredibly annoying at the same time. You know the one. That brassy, psychedelic-jazz fusion that feels like a carnival ride about to go off the rails.

It hit number two on the Billboard Hot 100. It stayed there for three weeks. Honestly, it probably would have hit number one if it weren't for the pesky persistence of Henry Mancini’s "Love Theme from Romeo and Juliet." But the charts don't tell the whole story. To understand why Spinning Wheel remains such a fascinating specimen of the late sixties, you have to look at the sheer chaos happening inside the arrangement.

Most pop songs are built on a predictable loop. Verse, chorus, verse, chorus, bridge, out. Not this one. This is a song that starts as a R&B powerhouse and ends with a literal "the circus is in town" flute melody and a musician saying, "That wasn't very good, was it?" into a live mic.

The Jazz-Rock Collision That Nobody Saw Coming

In 1968, the idea of a "brass rock" band was still a bit of a gamble. You had Chicago (then called Chicago Transit Authority) and Blood, Sweat & Tears leading the charge. David Clayton-Thomas, who wrote Spinning Wheel, wasn't even the original lead singer of the group. Al Kooper had founded the band, but after the first album, things shifted. Clayton-Thomas brought this Canadian blues-shouter energy that transformed the band's sound from experimental to commercially explosive.

The song itself is a masterclass in tension. It’s written in 4/4 time, but the horn arrangements by Fred Lipsius make it feel more complex. It's got that "doo-lang, doo-lang" backbeat that feels like a throwback to 1950s street-corner doo-wop, but then the horns stab through the mix with a precision that would make Duke Ellington proud. It’s a weird marriage. It shouldn't work. Jazz purists hated it because it was too poppy, and rock fans were suspicious of the sheet music and the lack of fuzzy guitars.

Yet, it worked.

People often forget how much "Spinning Wheel" relies on the element of surprise. About two-thirds of the way through, the song just... breaks. We get this dizzying, bebop-influenced trumpet solo from Lew Soloff. It’s fast. It’s jagged. It feels like a panic attack in a jazz club. For a few bars, you aren't listening to a pop hit anymore. You’re listening to a hard-bop session in a basement in Greenwich Village. Then, like a rubber band snapping back, the band falls right back into that thumping groove.

✨ Don't miss: Why ASAP Rocky F kin Problems Still Runs the Club Over a Decade Later

What Is This Song Actually About?

Lyrics in the late sixties were often a contest to see who could be the most cryptic. You had Dylan doing his thing, Lennon singing about walruses, and then you have Clayton-Thomas writing about a painted pony on a spinning wheel.

Is it about reincarnation? Maybe.

Is it about the cyclical nature of fame? Probably.

Is it just a bunch of cool-sounding words thrown together after a long night? Also a strong possibility.

The core message—"What goes up must come down"—is the oldest cliché in the book. But the song frames it as a warning. "Talkin' 'bout your troubles and you, you never learn." It’s a critique of the ego. The "spinning wheel" is life itself, or perhaps the fickle nature of the music industry that was already chewing through artists at a record pace.

There's a specific line that always stands out: "Did you find the directing sign on the straight and narrow highway?" It sounds like a jab at the burgeoning hippie movement, or maybe just a call to get your act together. The beauty of the song is that it’s vague enough to be an anthem for anyone who feels like they’re stuck in a loop.

The Infamous Ending and the "Mistake"

If you listen to the album version of Spinning Wheel on Blood, Sweat & Tears (their self-titled second album), it doesn't end with a fade-out. It ends with a train wreck.

The song collapses into a rendition of "The Irish Washerwoman" on a recorder or a flute. It’s jarring. Then you hear the laughter and the comment: "That wasn't very good, was it?" This was a deliberate choice by producer James William Guercio. He wanted to show the "human" side of the band. In an era where every studio recording was starting to feel overly polished, BS&T decided to leave the seams showing.

🔗 Read more: Ashley My 600 Pound Life Now: What Really Happened to the Show’s Most Memorable Ashleys

Ironically, the single version—the one most people heard on the radio—cut all of that out. It also cut the jazz solo. If you only know the radio edit, you're missing the soul of the track. You're getting the "easy listening" version of a song that was actually designed to be a bit of a middle finger to convention.

Why Musicians Still Study This Track

Ask any drummer about the beat in Spinning Wheel. Bobby Colomby’s work here is legendary. He isn't just keeping time; he’s playing melodies on the drums. The snare hits are crisp, and the way he interacts with the bass player, Jim Fielder, creates this impenetrable wall of rhythm.

Then there’s the horn section. We're talking about:

- Lew Soloff (Trumpet)

- Chuck Winfield (Trumpet)

- Jerry Hyman (Trombone)

- Fred Lipsius (Alto Sax)

These weren't just guys who could read music. They were improvisers. When you listen to the horn stabs in the chorus, notice how they aren't perfectly "clean." There’s a bite to them. There’s a little bit of dirt. That’s what separates "Spinning Wheel" from the Vegas-style show tunes that were trying to copy this sound in the early seventies.

The production was also top-tier for 1969. Guercio, who would go on to produce most of Chicago's early hits, knew how to capture the "air" in the room. You can hear the physical space between the instruments. This wasn't a "Wall of Sound" production; it was a "Room of Sound."

The Legacy of the "Blood, Sweat & Tears" Sound

It's easy to look back and think of this band as "dad rock" or something you’d hear in a dentist’s office. But at the time, this was radical. They won the Grammy for Album of the Year in 1970, beating out Abbey Road by The Beatles. Read that again. They beat Abbey Road.

💡 You might also like: Album Hopes and Fears: Why We Obsess Over Music That Doesn't Exist Yet

That’s how massive they were.

But fame is a spinning wheel. By the mid-seventies, the band’s lineup had changed so many times it was hard to keep track. Clayton-Thomas left, came back, left again. The "brass rock" sound became a caricature of itself. However, Spinning Wheel remains the high-water mark. It captured a moment when jazz and rock weren't just flirting; they were in a full-blown, messy relationship.

How to Truly Appreciate the Track Today

If you want to get the most out of this song, don't listen to a compressed MP3 on cheap earbuds. It’ll sound like a tinny mess.

- Find the 180g Vinyl or a Hi-Res FLAC: You need to hear the low-end frequency of that bass guitar. It’s what drives the whole machine.

- Listen for the Cowbell: It’s there. It’s subtle, but it’s the heartbeat of the chorus.

- Pay attention to the Stereo Spread: The horns are panned in a way that makes you feel like you’re standing in the middle of the rehearsal room.

- Compare the Single vs. Album Version: Note how much the jazz solo changes the "vibe." Without it, the song is a pop ditty. With it, it’s a manifesto.

Actionable Insights for Music Lovers

If you're a musician or a songwriter, there’s a lot to steal from Spinning Wheel.

First, stop being afraid of "the drop." That moment where the song feels like it’s falling apart before snapping back together is what gives it its replay value. It creates a "did I just hear that?" moment for the listener.

Second, consider your instrumentation. Adding a brass section isn't just about making things "louder." It’s about adding textures that a guitar simply cannot provide. The way the trumpets "scream" during the high notes of the chorus adds an emotional urgency that David Clayton-Thomas’s voice, as powerful as it is, couldn't achieve alone.

Finally, embrace the imperfection. That "That wasn't very good, was it?" ending is the most famous part of the song for many aficionados. It humanizes the giants. In our current era of AI-perfected, Auto-Tuned vocals, a little bit of genuine, recorded failure goes a long way.

To really dive into this era, your next move should be listening to the Child Is Father to the Man album by the original Al Kooper-led lineup. It’s a completely different beast, far more psychedelic and less "Vegas," but it provides the essential DNA for what Spinning Wheel eventually became. Follow that up by comparing the brass arrangements of BS&T with Chicago’s "25 or 6 to 4." You’ll start to see two very different philosophies on how to use a trumpet in a rock band. One is about power; the other, as seen in Spinning Wheel, is about the spin.