You're standing in the drugstore aisle. It’s August. The fluorescent lights are humming, and you’re staring at two bottles of sunscreen that look identical except for two digits and about five dollars in price. One says SPF 30. The other says SPF 50. Your brain does the math—50 is way higher than 30, right? It feels like it should be nearly double the protection.

It isn't. Not even close.

Understanding the difference between SPF ratings is one of those things where our collective common sense actually fails us. We’ve been conditioned to think of these numbers like a grade on a test or the speed of a car. But SPF—Sun Protection Factor—is a measure of time and percentages, and the scale is nowhere near linear. Honestly, the marketing departments of major skincare brands have spent decades leaning into this confusion because "more is better" is an easy sell.

If you’ve ever wondered why you still got a tan while wearing SPF 100, or if that SPF 15 in your moisturizer is actually doing anything at all, you aren't alone. Let's get into the weeds of how this actually works.

The Math Behind the Screen

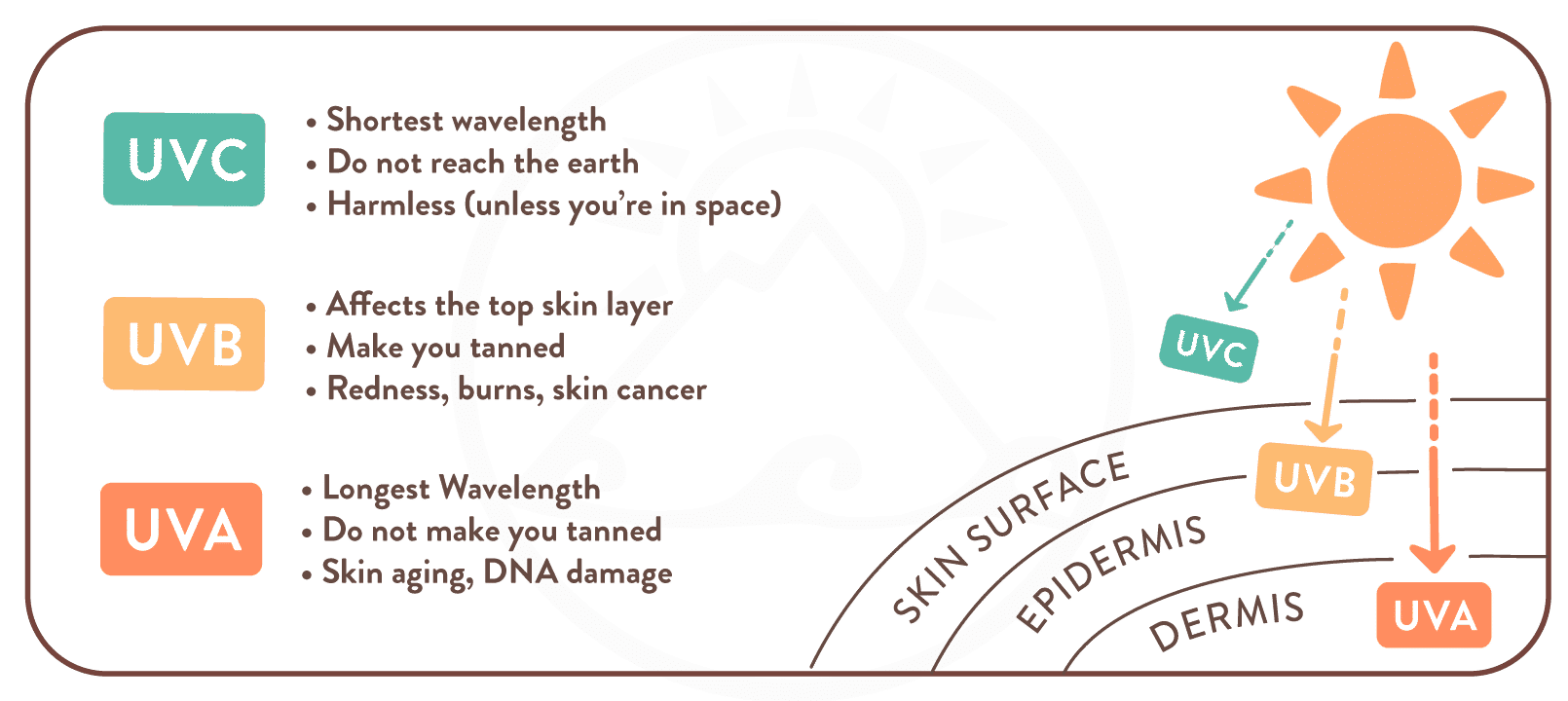

The Sun Protection Factor is specifically a measure of how much UVB radiation—the stuff that causes those painful, lobster-red burns—is required to redden protected skin compared to unprotected skin.

Think about it like this. If your skin normally starts to turn pink after 10 minutes in the direct July sun, applying an SPF 30 sunscreen theoretically means it would take 30 times longer for that same burn to occur. That’s 300 minutes.

But here is where it gets weird.

💡 You might also like: How to Treat Uneven Skin Tone Without Wasting a Fortune on TikTok Trends

The difference between SPF 30 and SPF 50 in terms of actual UVB rays blocked is tiny. SPF 15 blocks about 93% of UVB rays. SPF 30 jumps up to roughly 97%. When you move up to SPF 50, you’re hitting about 98%.

Wait. Read that again.

The jump from 30 to 50 only gives you a 1% increase in actual protection. If you go all the way to SPF 100? You're looking at 99%. You are paying a premium for a literal handful of percentage points. This is why the FDA has historically toyed with the idea of capping labels at "SPF 50+" because they worry that higher numbers give people a false sense of "sun armor," leading them to stay out way too long without reapplying.

Why High SPF Often Fails in the Wild

So, if SPF 50 blocks 98% of rays, why do people still burn?

It’s usually the "application gap." Most people apply about a third of the amount of sunscreen used in lab testing. In a clinical setting, researchers slather on 2 milligrams of product per square centimeter of skin. In the real world? You’re probably using a nickel-sized dollop for your whole face and a quick spray for your legs.

When you under-apply an SPF 50, you aren't getting SPF 25. The math is more aggressive than that. You might only be getting the equivalent of an SPF 7 or 8.

📖 Related: My eye keeps twitching for days: When to ignore it and when to actually worry

There's also the "Broad Spectrum" problem. SPF only measures UVB. It tells you nothing about UVA rays, which are the ones that penetrate deeper, cause premature aging, and contribute to skin cancer without ever leaving a burn. You could have an SPF 100 that sucks at blocking UVA. Always, always look for the words "Broad Spectrum" or the PA++++ rating if you’re looking at Korean or Japanese sunscreens.

The Reapplication Trap

The biggest difference between SPF levels isn't how well they work, but how they influence our behavior.

Psychologically, if you put on SPF 100, you feel invincible. You stay in the pool for four hours. You forget to reapply. But sunscreen is a filter, not a shield. It breaks down. The active chemicals—whether they are mineral like Zinc Oxide or chemical like Avobenzone—degrade as they absorb UV radiation. Plus, you’re sweating. You’re wiping your face with a towel. You’re jumping in the ocean.

By hour three, that SPF 100 is likely providing less protection than a freshly applied layer of SPF 15.

Dr. Steven Wang, a renowned dermatologist and chair of the Skin Cancer Foundation’s Photobiology Committee, has often pointed out that the high-SPF "safety net" is mostly an illusion if the application isn't perfect. It’s better to use an SPF 30 that you actually enjoy wearing—and will therefore apply generously—than an SPF 70 that feels like thick, sticky paste and makes you look like a ghost.

Breaking Down the Ingredients

What’s actually inside the bottle matters more than the number on the front. Generally, you’ve got two camps:

👉 See also: Ingestion of hydrogen peroxide: Why a common household hack is actually dangerous

- Mineral (Physical): These use Zinc Oxide or Titanium Dioxide. They sit on top of the skin and reflect UV rays like a mirror. They’re great for sensitive skin but often leave that "white cast."

- Chemical: These use ingredients like Oxybenzone, Octisalate, or Avobenzone. They absorb into the skin and turn UV rays into heat, which is then released from the body. They feel lighter and look invisible, but some people find them irritating.

The difference between SPF in mineral vs. chemical forms usually comes down to texture. Achieving an SPF 50 with pure Zinc Oxide requires a lot of powder, which is why those high-numbered mineral sticks can feel like diaper cream. Newer "micronized" formulas are better, but there's always a trade-off between protection level and cosmetic elegance.

Environmental and Health Nuances

We can't talk about sunscreen in 2026 without mentioning reef safety. Hawaii and several other island nations have banned Oxybenzone and Octinoxate because they contribute to coral bleaching.

Does a higher SPF mean more chemicals? Usually, yes. To get from 30 to 100, manufacturers have to increase the concentration of active filters. If you have hyper-reactive skin or are worried about hormonal disruptors, sticking to a solid SPF 30 with a simpler ingredient list is often the smarter play.

Real-World Protection Strategy

If you really want to protect your skin, stop obsessing over the number and start looking at your watch.

- The Two-Finger Rule: Squeeze two strips of sunscreen down your index and middle fingers. That is the amount you need just for your face and neck.

- The "Shot Glass" Rule: You need a full ounce (roughly a shot glass) to cover an adult body in a swimsuit. Most people get about four uses out of a bottle when they should be getting one or two.

- The Window Fallacy: UVA rays go through glass. If you sit by a sunny window at work all day, you are still accumulating skin damage. This is where a lower SPF (like 15 or 20) in a daily moisturizer actually makes sense.

The real difference between SPF values is marginal once you pass 30. If you are fair-skinned, have a history of skin cancer, or are using photosensitizing medications (like Retinol or certain antibiotics), sure, grab the 50. But don't let the number trick you into staying out until sunset without a second coat.

Actionable Steps for Better Protection

Instead of just buying the highest number you can find, try this approach:

- Check the Date: Sunscreen expires. The active filters lose their punch over time. If that bottle has been in your beach bag since 2023, toss it.

- Layer Up: Use a Vitamin C serum underneath your sunscreen. Antioxidants help neutralize the free radicals that manage to slip past your SPF's defenses.

- Texture is King: Find a formula you love. If it’s greasy, you won't use enough. If it stings your eyes, you’ll skip your eyelids (where skin cancer is common).

- Wait 15 Minutes: Chemical sunscreens need time to "set" and bond with your skin before they are fully effective. Don't apply it while standing on the sand; apply it before you leave the house.

- Don't Forget the Extras: Ears, the tops of feet, the part in your hair, and the backs of your hands. These are the spots dermatologists most frequently have to treat for squamous cell carcinoma.

The most effective sunscreen in the world isn't the one with the highest SPF—it’s the one you actually wear every single day. Stop chasing the 1% difference between 30 and 50 and start focusing on the 100% difference between wearing it and leaving it on the counter.