Ever stared at the "Estimated Time of Arrival" on your dashboard and wondered why it’s fluctuating like a nervous heartbeat? It’s basically physics. At its core, every navigation app on the planet is running a variation of one specific, ancient rule: speed equals distance divided by time.

It sounds simple. Almost too simple. If you’re driving 60 miles and you’re going 60 miles per hour, you’ll be there in an hour. Easy math. But reality is messy. Traffic lights happen. Someone decides to drive 40 in a 55. A literal cow blocks the road in rural Vermont. Suddenly, that elegant equation feels like a lie.

Most people learn this formula in middle school and then promptly forget how it actually dictates their entire life, from how fast their internet downloads a 4K movie to how NASA lands a rover on Mars.

The Math Nobody Told You Was This Simple

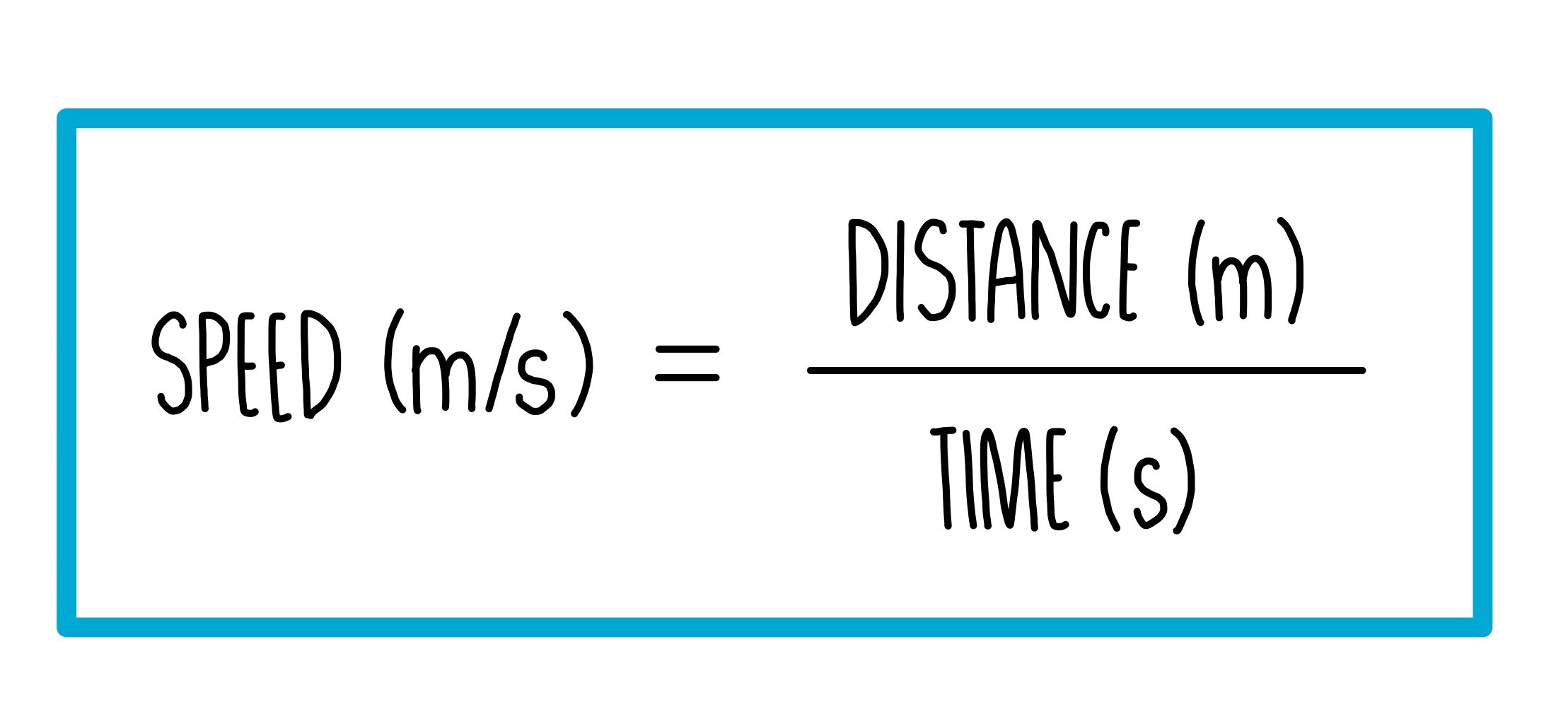

If we’re being technical—and honestly, we should be—the formula is usually written as $v = \frac{d}{t}$.

In this scenario, $v$ is velocity (or speed, if we aren't worried about direction), $d$ is distance, and $t$ is time. It’s the "Golden Triangle" of physics. If you have two of those numbers, the third one is a captive audience. You can't change one without the others reacting. It’s a cosmic see-saw.

Think about it this way. If you want to get to your destination faster, you have two choices. You can either shorten the distance—shortcuts are great until they aren't—or you can increase your speed. Since you can’t usually warp space-time to make your office closer to your house, you press the gas pedal. But here is where it gets weird.

Why Your Speedometer and Your GPS Disagree

Have you noticed your car’s speedometer usually says you’re going faster than your phone says you are?

That’s not a glitch. Car manufacturers often calibrate speedometers to "over-read." They’d rather you think you’re going 72 mph when you’re actually doing 68 mph, mostly to avoid lawsuits and keep you under the speed limit. Your phone, however, uses high-frequency GPS pings to calculate your speed equals distance divided by time ratio in real-time.

Your phone tracks where you were at Point A and where you are at Point B. It measures that literal distance and divides it by the seconds that passed between pings. Because GPS measures your actual movement over the earth’s crust rather than how fast your tires are spinning, it’s usually the more "honest" number.

Tire wear actually messes this up too. As your tires go bald, their diameter shrinks. A smaller tire has to spin more times to cover the same distance. Your car thinks you’re flying; physics knows you’re lagging.

The Difference Between Speed and Velocity

Physics teachers love to get pedantic about this. Speed is a "scalar" quantity. It just cares about how fast you’re moving. 100 mph is 100 mph.

Velocity is a "vector." It cares about direction. If you drive in a perfect circle at 100 mph, your average speed is high, but your average velocity is technically zero because you ended up exactly where you started. You didn't actually "go" anywhere in terms of displacement.

Real-World Chaos: The "Average Speed" Trap

We’ve all done the "mental math" on a road trip. You see a sign that says "Chicago: 120 Miles." You’re doing 80 mph. You think, I’ll be there in 90 minutes. You won't.

This is where the speed equals distance divided by time formula meets the harsh reality of human error. You haven't accounted for the three-minute bathroom break, the slow-down for a construction zone, or the fact that you have to decelerate to take an off-ramp.

Your "instantaneous speed" might be 80, but your "average speed" for the trip will likely be closer to 62. In the world of logistics—think Amazon or FedEx—this distinction is worth billions of dollars. They don't care how fast their vans can go; they care about the average speed over an eight-hour shift.

Logistics and the "Last Mile"

In the shipping industry, the distance is fixed. The warehouse is where it is, and your house isn't moving. To make more money, they have to manipulate the time variable.

But they can't just tell drivers to speed; that leads to accidents and insurance hikes. So, they use algorithms to optimize the distance. By shaving 0.4 miles off a thousand different routes, they effectively lower the time required without ever touching the speed variable.

The Evolution of Measuring Pace

Back in the day, "speed" was measured in "days' journey" or "leagues." It was incredibly subjective. If you had a slow horse, the distance felt longer.

It wasn't until the late 1600s, thanks to guys like Pierre Gassendi and later Christiaan Huygens, that we started getting serious about measuring the speed of sound and light. They used the same core logic: find a known distance, trigger an event, and see how long it takes to hear or see it.

When researchers first measured the speed of light, they used the moons of Jupiter. Ole Rømer noticed that the timing of eclipses of Jupiter’s moon Io changed depending on where Earth was in its orbit. He realized the speed equals distance divided by time formula applied to light itself. When Earth was farther from Jupiter, the "distance" was higher, so the "time" it took for the light to reach his telescope increased.

He wasn't just looking at stars; he was looking at the fundamental speed limit of the universe.

How to Actually Use This in Your Daily Life

Stop looking at your speedometer as a goal. If you want to save time, you’re better off eliminating stops than you are driving faster.

Mathematically, increasing your speed from 60 mph to 70 mph on a 10-mile trip only saves you about 85 seconds. Is that worth a $200 speeding ticket? Probably not.

However, if you can cut two miles off that 10-mile trip by finding a better route, you save significantly more time without even trying to go fast. This is why "distance" is usually the more powerful variable in the equation for us mere mortals.

Actionable Insights for the Road

- Check your "Average Speed" on your car's trip computer. You’ll be shocked at how low it is. Most city drivers average about 18–25 mph despite frequently hitting 45 mph between lights.

- Inflate your tires. As mentioned, tire diameter changes your car’s internal distance calculation. Properly inflated tires ensure your odometer and speedometer stay as accurate as possible.

- Trust the GPS over the dashboard. If you’re trying to calculate a precise arrival time, the GPS uses satellite trilateration to solve for $t$ far more accurately than your car’s mechanical sensors can.

- The 3-Second Rule. This is the formula in safety form. To maintain a safe distance, you don't measure feet; you measure time. When the car in front passes a shadow, you should reach that same shadow three seconds later. You are literally using time to ensure you have enough distance to react to a change in speed.

The universe runs on these three variables. Whether it’s a marathon runner pacing themselves for a sub-four-hour finish or a data packet traveling through an undersea fiber-optic cable, it all comes back to the same thing. You can't outrun the math.

🔗 Read more: iOS 18 beta download: What Most People Get Wrong

To master your schedule, stop fighting the speed and start looking at the distance. That's where the real time is saved.

Next Steps for Accuracy:

If you're planning a long-distance trip, calculate your "Actual Average Speed" by taking your total odometer miles and dividing them by the total engine-on hours from your last trip. Use that number—not the speed limit—to plan your next departure time. You'll find your arrival estimates become eerily accurate.