Ever wonder why the sand at the beach feels like molten lava under your feet, but the ocean water right next to it is freezing? It’s the same sun hitting both. They’re in the same location. Yet, one wants to blister your toes and the other makes your teeth chatter. This isn't some weird glitch in the matrix. It’s actually the perfect real-world demo of specific heat.

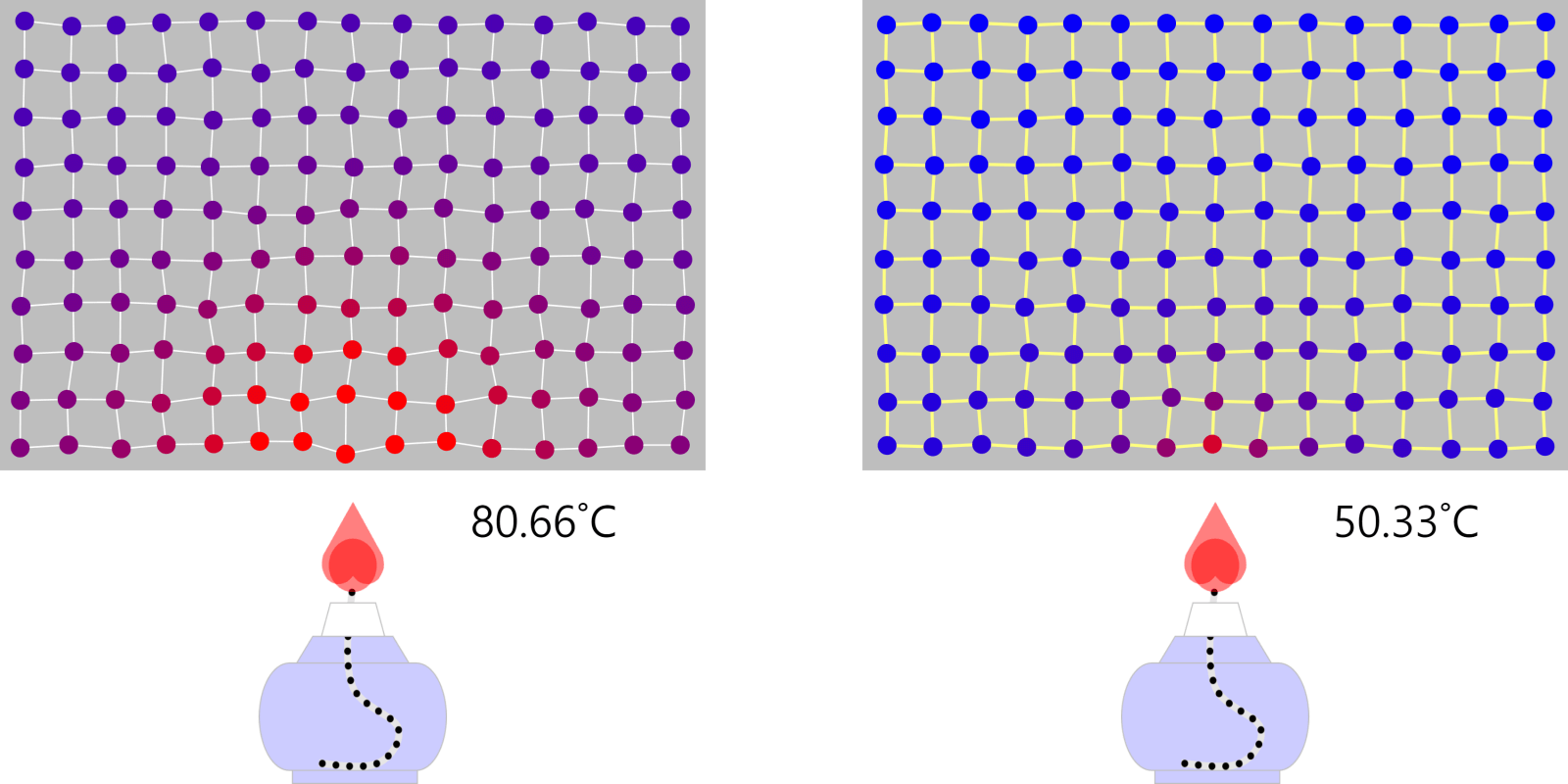

Basically, specific heat capacity is a measure of how much "thermal energy" you have to cram into a substance to make its temperature budge. Some materials are total lightweights—they get hot the second you look at them. Others are like giant sponges; they can soak up massive amounts of heat before the thermometer even flinches.

In technical terms, we define the specific heat capacity ($c$) as the amount of heat ($Q$) required to raise the temperature of one gram (or kilogram) of a substance by one degree Celsius (or Kelvin). Mathematically, it looks like this:

$$Q = mc\Delta T$$

Where $m$ is the mass and $\Delta T$ is the change in temperature. But honestly, unless you're cramming for a physics mid-term, the math is less interesting than how this stuff actually dictates your daily life.

Why Water is the Weirdest Thing in Your Kitchen

If you’ve ever waited for a pot of water to boil for pasta, you know it takes forever. You’re standing there, staring at the burner, wondering if the stove is broken. It’s not. Water just has an incredibly high specific heat.

To be precise, liquid water has a specific heat of about $4.184\text{ J/g°C}$. Compare that to the copper pot you're using, which sits at roughly $0.385\text{ J/g°C}$. That’s a massive difference. The metal pot heats up almost instantly because it’s an efficient conductor with low specific heat, while the water molecules are busy vibrating and stretching their hydrogen bonds, absorbing all that energy before they actually start moving fast enough to register as "hot."

🔗 Read more: Siri Class Action Lawsuit: What Really Happened With Your Privacy

This high capacity is why the Earth is habitable. Our oceans act as a giant thermal buffer. They soak up the sun's energy during the day without boiling off and release it slowly at night so we don't turn into popsicles. It's also why a coastal city like San Diego has pretty chill weather year-round, while a city in the middle of a desert oscillates between "oven" and "freezer" in a single 24-hour cycle. No water nearby to regulate the temperature.

The Materials That Just Can't Handle the Heat

On the flip side, metals are generally the "fast burners" of the world. Take gold, for example. It has a specific heat of only $0.129\text{ J/g°C}$. If you put a gold bar and a bowl of water under the same heat lamp, that gold is going to be untouchable while the water is still lukewarm.

This isn't just trivia. Engineers have to obsess over these numbers. When you’re designing a CPU for a high-end gaming rig or an electric vehicle battery, you need to know exactly how much heat these components can take before they melt. Aluminum is often used in heat sinks not just because it's cheap, but because it has a relatively high specific heat for a metal ($0.897\text{ J/g°C}$), meaning it can pull a lot of heat away from the sensitive chips before it gets too hot itself.

A Quick Reality Check on Different Substances

- Lead: $0.128\text{ J/g°C}$ (Heats up incredibly fast)

- Iron/Steel: $\approx 0.450\text{ J/g°C}$ (The standard for your frying pans)

- Air: $\approx 1.005\text{ J/g°C}$ (Low density makes it feel different, but it’s a poor heat storer)

- Water: $4.184\text{ J/g°C}$ (The absolute champion of common liquids)

Cooking and the "Pizza Mouth" Incident

We've all been there. You bite into a slice of pizza. The crust is fine. The cheese is okay. But then you hit that pocket of tomato sauce and—BAM—third-degree burns on the roof of your mouth.

📖 Related: Apple iPhone Production India 2025: What’s Actually Happening on the Factory Floor

That is specific heat in action.

The crust is porous and dry, meaning it has a lower specific heat and doesn't hold much thermal energy. The sauce, however, is mostly water. It has trapped a huge amount of energy. Even if the crust and the sauce are at the exact same temperature, the sauce has more "heat" to dump into your skin. It’s a literal energy bomb waiting for your palate.

Beyond the Basics: Phase Changes and Latent Heat

It's tempting to think that adding heat always raises temperature. It doesn't.

When you reach a boiling point or a melting point, the temperature stops rising. You keep pumping energy in, but the thermometer stays stuck at $100\text{°C}$ (for water). This is where specific heat hands the baton over to latent heat. The energy is no longer being used to make molecules move faster; it’s being used to break the bonds holding them together.

This is why steam burns are so much worse than boiling water burns. When steam hits your skin, it condenses back into water, releasing all that "hidden" latent heat it stored while boiling, plus the heat it loses as it cools down to your body temperature. It’s a double whammy of thermal transfer.

What This Means for the Future of Technology

As we push toward 2026 and beyond, specific heat is becoming a massive deal in the world of green energy. Think about concentrated solar power. We aren't just using mirrors to make electricity directly; we're using them to heat up substances with high specific heat—like molten salts. These salts can hold onto that heat for hours, allowing us to generate electricity even after the sun goes down.

Then there’s the cooling of data centers. With AI models getting more complex, servers are putting out more heat than ever. Companies are moving away from air cooling (which is inefficient due to air's low density and moderate specific heat) toward liquid immersion cooling. They literally dunk the servers in special dielectric oils that have a high capacity to whisk away heat without causing a short circuit.

📖 Related: Apple Store Oakridge: What to Know Before You Head to the Mall

Practical Takeaways for Your Life

Understanding specific heat isn't just for scientists. It's for anyone who wants to be more efficient.

- Cast Iron vs. Stainless Steel: Cast iron has a lower specific heat than you'd think, but it’s dense. It takes a while to get hot, but once it's there, its mass allows it to hold a ton of energy. This is why it sears steak better than a thin aluminum pan.

- Insulation Strategy: If you live in a place with wild temperature swings, materials with high "thermal mass" (high specific heat and high density), like brick or concrete, can keep your house cooler in the day and warmer at night.

- Emergency Cooling: If you need to cool a drink fast, don't just put it in the freezer. Put it in a salt-water ice bath. The water provides more surface contact and has the specific heat capacity to pull warmth out of your soda way faster than the air in a freezer ever could.

Next time you’re burning your feet on the sand or waiting for the kettle to whistle, remember that you're witnessing one of the most fundamental properties of matter. It’s the reason our coffee stays hot, our cars stay cool, and our planet stays alive.

To put this into practice, start paying attention to the materials in your kitchen or your tech. If something feels like it’s "holding heat" too long, check its moisture content or its density. You’ll start seeing the world as a giant exchange of energy, all governed by that one little number: $c$.**