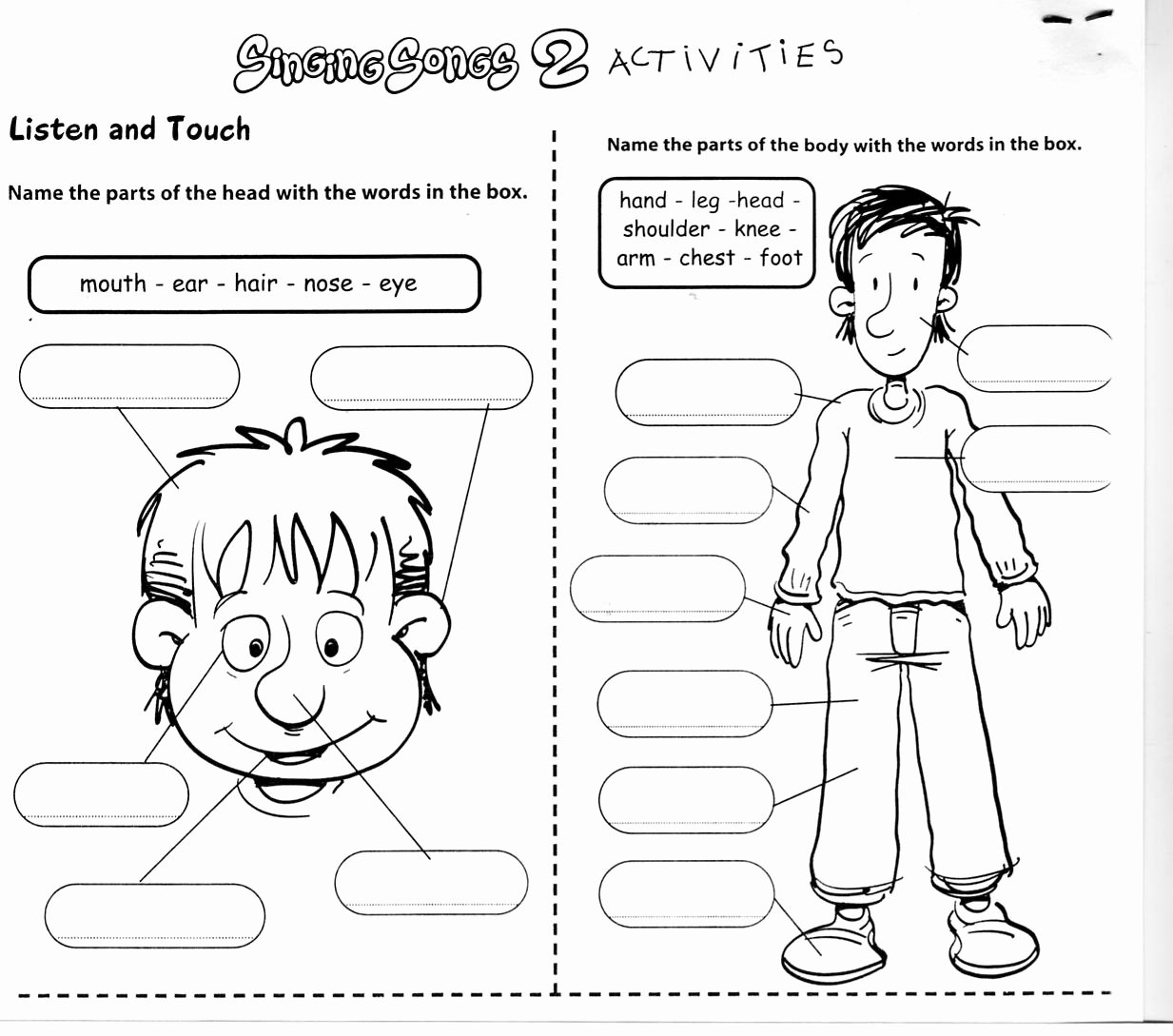

You're staring at a diagram. It's a stick figure, maybe a slightly more detailed cartoon if the creator was feeling fancy. There are lines pointing to the nose, the toes, and that weird space between the shoulder and the neck. You need a spanish parts of the body worksheet because, honestly, trying to explain to a pharmacist in Madrid that your "thingy near your stomach" hurts is an exercise in pure humiliation. We've all been there.

Spanish is rhythmic. It’s phonetic. But for some reason, the vocabulary for anatomy feels like a massive hurdle for English speakers. Why? Because we rely too much on "cognates"—words that look the same in both languages—and then get slapped in the face when la mano (the hand) ends in an "o" but takes a feminine article. It’s a trap.

Most people download a PDF, fill it out in five minutes, and think they’ve mastered the language. They haven't. They've just performed a matching game. If you actually want to use these words in a doctor’s office or while describing a workout at a gym in Mexico City, you need to change how you interact with that piece of paper.

The Gender Trap Most Students Fall Into

Let’s talk about la mano. It’s the classic "gotcha" of Spanish 101. You see a worksheet, you see a hand, and you want to write el mano. It makes sense, right? Almost every other word ending in "o" is masculine. But Spanish loves to be difficult. It’s la mano.

Then you have el brazo (the arm) and la pierna (the leg). Simple enough. But then you hit the pluralization. If you’re using a spanish parts of the body worksheet, you’ll likely see a list of singular terms. In real life, things come in pairs. You don't just have an eye; you have los ojos. You don't just have a lung; you have los pulmones.

If your worksheet doesn't force you to switch between singular and plural articles, it’s failing you. The brain needs to associate the article (el, la, los, las) as part of the word itself. Don't learn cabeza. Learn la cabeza. If you don't, you'll spend your whole life sounding like a caveman. "My head hurt." No. "Me duele la cabeza."

Why Rote Memorization is a Waste of Time

I've seen thousands of students do this. They print out a sheet, write la nariz next to the nose, and move on. Two days later? Gone. Erased from the hard drive.

The human brain is remarkably efficient at deleting useless information. If you don't attach a sensory experience or a "need" to the word, it won't stick. Experts like Dr. Paul Pimsleur, who pioneered language learning systems, emphasized that memory is tied to recall intervals. A static worksheet is just a snapshot.

👉 See also: Why People That Died on Their Birthday Are More Common Than You Think

Instead of just labeling, try this: touch the part of your body as you write it. It sounds silly. It feels even sillier. But proprioception—the sense of your body's position—is a powerful mnemonic device. When you write el codo (the elbow), actually grip your elbow. Feel the bone.

Common Body Parts You’ll Actually Use

Most worksheets give you the basics. Head, shoulders, knees, and toes. Thanks, Dr. Seuss. But what about the stuff that actually matters?

- La garganta (The throat): Because you’re going to get a cold eventually.

- La espalda (The back): Essential for anyone over the age of 25.

- El tobillo (The ankle): If you’re hiking in the Andes, this is the word you need when you trip.

- Las muñecas (The wrists): Funny enough, this also means "dolls." Context is everything.

Imagine you're at a farmacia in Bogotá. You don't need to know how to say "patella." You need to say your "rodilla" (knee) is swollen. If your worksheet focuses on medical jargon before basic survival anatomy, recycle it.

The Secret of Reflexive Verbs

Here is where the spanish parts of the body worksheet usually fails to explain the "why." In English, we say "I wash my hands." In Spanish, you say "Me lavo las manos."

Notice the difference? Spanish speakers don't "possess" their body parts the same way we do. Using mis manos (my hands) sounds redundant to a native speaker. They already know they are your hands because you used the reflexive verb me lavo.

If you’re filling out a worksheet, try writing a sentence next to each label.

"Me duele la espalda." (My back hurts.)

"Me cepillo los dientes." (I brush my teeth.)

This shifts the learning from "noun identification" to "functional communication." It’s the difference between knowing what a hammer is and knowing how to drive a nail.

✨ Don't miss: Marie Kondo The Life Changing Magic of Tidying Up: What Most People Get Wrong

Regional Variations That Will Confuse You

Spanish isn't a monolith. The Spanish spoken in Madrid isn't the same as the Spanish in Buenos Aires or Mexico City. This applies to the body, too.

Take the word for "stomach." You’ll see el estómago on every worksheet. It’s clinical. It’s safe. But in common conversation? You might hear la panza or la barriga. If you're talking to a kid, it’s la tripita.

And then there's the "waist" vs. "hips" debate. La cintura is your waist—where a belt goes. Las caderas are your hips. Many learners mix these up because, in English, we often use them interchangeably when talking about movement. But try telling a dance instructor in Cuba to move their cintura when they’re trying to teach you to move your caderas. They’ll laugh.

How to Design Your Own Practice

Stop looking for the "perfect" PDF. They don't exist. Most are created by people who haven't stepped foot in a classroom in a decade. Instead, take a blank piece of paper and draw a person. It doesn't have to be good.

- Label the "Action" Zones: Focus on the parts of the body you use for your hobbies. If you’re a runner, focus on los muslos (thighs), las pantorrillas (calves), and los talones (heels).

- Color Code by Gender: Use a blue pen for masculine nouns (el costal) and a red pen for feminine ones (la costilla). Visual cues are a shortcut for your brain.

- The "Pain" Test: Imagine you’re at a doctor. Circle three parts of the body and write down a symptom for each. "Tengo un calambre en la pierna" (I have a cramp in my leg).

This makes the spanish parts of the body worksheet a living document. It becomes a tool for survival rather than a chore for a grade.

The Biological Connection

Interestingly, our brains process body-related words differently. A study published in the journal NeuroImage showed that when we hear words related to body parts or actions, the corresponding motor cortex in our brain actually lights up.

When you see the word la lengua (the tongue), your brain’s motor neurons for the tongue twitch ever so slightly. This is why language is physical. You aren't just learning labels; you are mapping your own physical existence into a new linguistic framework.

🔗 Read more: Why Transparent Plus Size Models Are Changing How We Actually Shop

Beyond the Worksheet: Real-World Application

If you really want to lock this in, get away from the paper. Go to a yoga class in Spanish on YouTube. Try a "Cuerpo Completo" (Full Body) workout. When the instructor yells "¡Abdomen contraído!" you’ll know exactly what to do. You’ll feel the burn in your músculos, and that physical pain will cement the vocabulary better than any highlighter ever could.

Don't ignore the "hidden" parts either. Worksheets love the face. Los ojos, la nariz, la boca. Fine. But learn el hígado (the liver) or los riñones (the kidneys). Why? Because if you’re ever in a situation where you need to discuss health or diet, these are the words that carry the most weight.

A Quick Reality Check

You're going to forget. You'll call your "fingers" (dedos) "toes" (dedos del pie) at least once. It's fine. Spanish speakers are generally thrilled you're even trying. The goal isn't perfection; it's being understood.

If you can point to your pecho (chest) and say "duele" (it hurts), you’ve won. The nuances of grammar can wait. The spanish parts of the body worksheet is just the map. You still have to drive the car.

Next Steps for Mastery

To turn this knowledge into a permanent skill, move beyond the static page. Start by identifying three body parts every morning while you get dressed, using the reflexive "me" format (e.g., "me pongo la camisa en los hombros").

Once that feels natural, find a partner or use a recording app to describe a physical sensation in a specific body part. Focus on the distinction between el and la, as this is the most common error that marks a "gringo" accent. Finally, look up a "Dolores de Cuerpo" (Body Aches) chart used in clinics; these real-world documents often contain more practical vocabulary than any standard classroom worksheet.