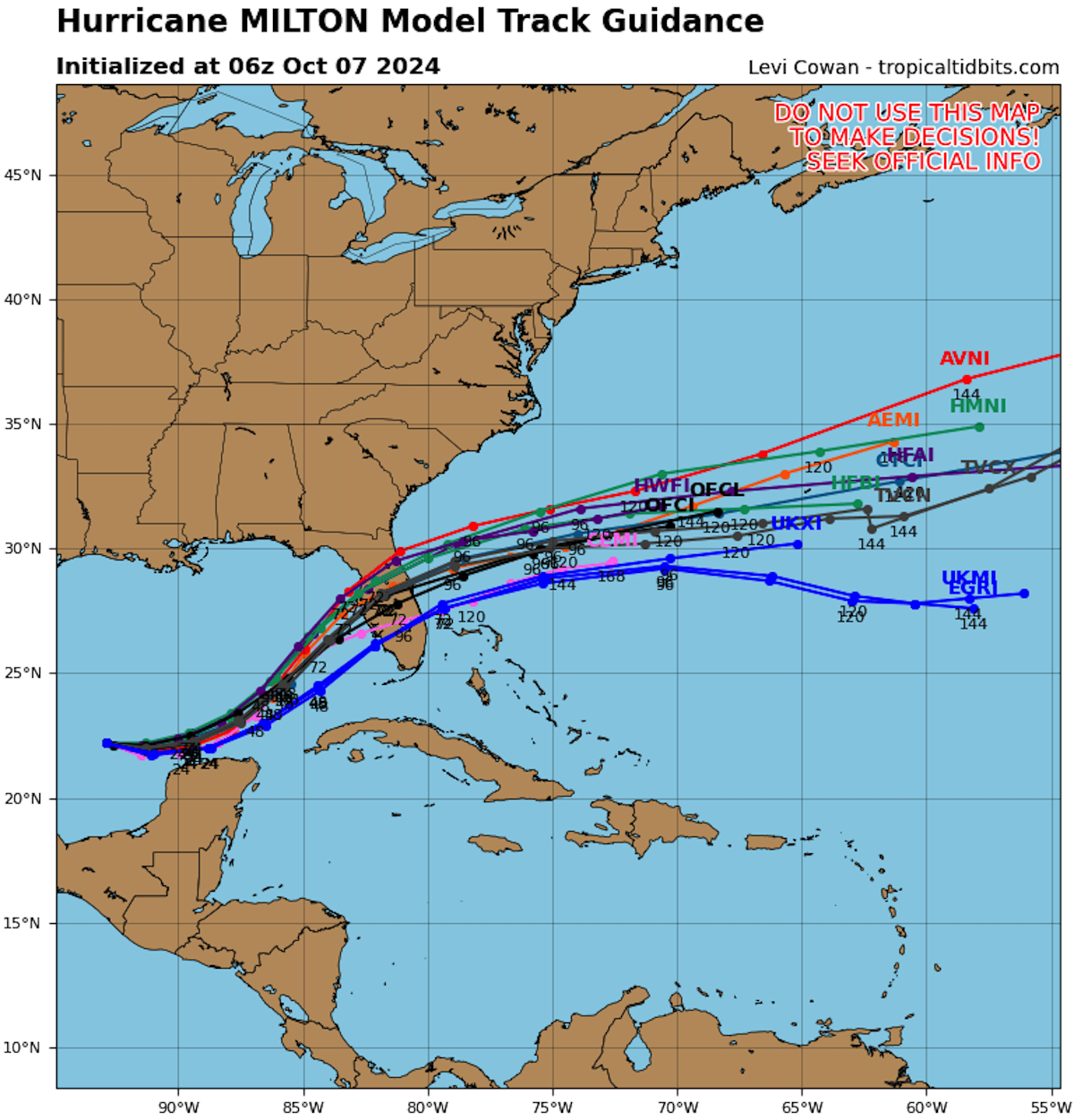

You've seen them. Those chaotic, neon-colored lines squiggling across a map of the Gulf of Mexico like a toddler went rogue with a box of highlighters. During the terrifying lead-up to Hurricane Milton’s landfall in October 2024, these spaghetti models for Milton were everywhere—plastered on social media, looping on local news, and being dissected by every amateur meteorologist with a smartphone.

But here’s the thing. Most people look at those lines and think they’re looking at a menu of choices. They pick the one that misses their house and breathe a sigh of relief. Or they see a line heading straight for them and panic. Both reactions kinda miss the point of what these models are actually trying to tell us.

The Chaos Behind the "Noodles"

Basically, a spaghetti model is just a visual representation of several different computer simulations. Each line represents a different model’s "opinion" on where the center of the storm is going. When you saw the spaghetti models for Milton while it was still churning near the Yucatan Peninsula, those lines were all over the place.

Why the mess? Because the atmosphere is incredibly fickle.

One model might assume a high-pressure ridge over the Atlantic is slightly stronger than another model does. That tiny difference—just a fraction of a percent in barometric pressure—can result in a path that shifts 100 miles north or south over a three-day period. For Milton, the big question wasn't just if it would hit Florida, but where on the west coast the hammer would fall.

🔗 Read more: Nate Silver Trump Approval Rating: Why the 2026 Numbers Look So Different

Why Consensus Matters More Than Any Single Line

If you looked at the models on October 7th, you might have seen one rogue line pointing toward the Panhandle and another diving toward the Keys. You’ve gotta ignore the outliers. Meteorologists look for "clustering."

When thirty different models—the GFS, the European (ECMWF), the UKMET, and various ensembles—all start hugging the same stretch of coastline, that’s when the pros start getting really worried. For Milton, the clustering around the Tampa Bay and Sarasota regions was remarkably tight several days out. It was a rare, chilling "agreement" among the machines.

The Famous Names You Kept Seeing

Not all noodles are created equal. If you were tracking the spaghetti models for Milton, you probably noticed a few specific acronyms popping up constantly.

- GFS (Global Forecast System): This is the American flagship. It’s a solid workhorse, but sometimes it gets a bit "excited" and over-forecasts intensity.

- ECMWF (European Center for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts): Often called "The Euro." It’s historically been the gold standard for track accuracy.

- HWRF and HMON: These are "hurricane-specific" models. Unlike the GFS, which looks at the whole world, these zoom in on the storm itself to understand its internal structure.

- GEFS/EPS Ensembles: These are the most important ones. Instead of running a model once, scientists run it 20 or 50 times with slightly different starting data. This creates a "bundle" of lines that shows the true range of uncertainty.

Honestly, the spaghetti models for Milton performed exceptionally well, but they also highlighted a massive misconception: the "line" isn't the storm.

💡 You might also like: Weather Forecast Lockport NY: Why Today’s Snow Isn’t Just Hype

It’s a Storm, Not a Point

One of the biggest mistakes people made while watching Milton’s approach was focusing entirely on the center line. They thought if the spaghetti noodle didn't cross their county, they were safe.

Milton was a monster. By the time it approached landfall as a Category 3, its wind field had expanded significantly. Even though the "center" of the spaghetti models for Milton eventually settled on a path near Siesta Key, the impacts—the storm surge, the inland flooding, and those horrific tornadoes—felt like they were happening everywhere at once.

The models predict the center. They don't predict how far the rain reaches or where a tornado might spin up on the "dirty side" of the storm.

The Accuracy Gap

While the track (the "where") was predicted with haunting accuracy days in advance, the intensity (the "how strong") was a different story. Milton went from a tropical storm to a Category 5 in basically the blink of an eye.

📖 Related: Economics Related News Articles: What the 2026 Headlines Actually Mean for Your Wallet

The spaghetti models are great at steering, but they struggle with the physics of "rapid intensification." That’s where the human element—the experts at the National Hurricane Center—comes in to bridge the gap between what the computer says and what the ocean is actually doing.

How to Use This Information Next Time

When the next big one enters the Gulf and the spaghetti models for Milton are replaced by a new set of colorful lines, don't just stare at the screen.

First, look for the "tightness" of the cluster. If the lines are spread out like a fan, the forecast is low-confidence. If they look like a single thick rope, start packing your bags.

Second, check the ensembles. If the "Euro" ensemble and the "GFS" ensemble agree, the probability of that path is very high.

Finally, remember the "Cone of Uncertainty." The National Hurricane Center’s cone is actually built using these spaghetti models. The cone is designed to contain the actual path of the storm 67% of the time. If you’re in the cone, or even near it, the specific "noodle" doesn't matter. You’re in the danger zone.

Practical Steps for Future Storm Tracking

- Use Reputable Sources: Avoid "weather hype" accounts on social media that post single outlier models to get clicks. Stick to sites like Tropical Tidbits or the National Hurricane Center.

- Ignore "Model Long-Range": A spaghetti model showing a hit 10 days out is basically science fiction. Focus on the 3-to-5-day window.

- Focus on the Spread: Use the width of the spaghetti cluster to gauge how much time you have to make a decision. A wide spread means you have time to watch; a tight cluster means it's time to act.

- Prepare for the Area, Not the Line: Assume the impacts will extend 100–150 miles from whichever line you’re looking at.

The spaghetti models for Milton were a triumph of modern science, giving millions of people the lead time they needed to get out of harm's way. They aren't perfect, and they'll never be a crystal ball, but understanding how to read them is a literal life-saving skill.