Getting to space is basically just a giant explosion that you try to point in the right direction. But coming home? That’s where the real physics starts to get scary. When you look at the space shuttle re entry, most people think it’s just a glider floating back to a runway. It isn't. It is an 80-ton brick of aluminum and ceramic tiles screaming through the upper atmosphere at twenty-five times the speed of sound. If you get the angle wrong by even a tiny bit, you either skip off the atmosphere like a stone on a pond or you burn up into a streak of plasma before anyone even sees you.

It's violent.

The Shuttle wasn't really a plane during those first few minutes of descent. It was a spacecraft trying its best to turn kinetic energy into heat without killing the seven people sitting in the cockpit.

The 40-degree nose-up gamble

The whole process starts with a "deorbit burn." This isn't some massive Hollywood engine blast. It’s a calculated nudge. While upside down and backward, the crew fires the Orbital Maneuvering System (OMS) engines for about three minutes. This slows the vehicle down just enough—around 200 miles per hour—to let gravity take over. Once that's done, they flip the ship. They have to. They need to meet the atmosphere at a very specific 40-degree angle.

Why 40 degrees?

💡 You might also like: 240 Knots to MPH: Why This Specific Speed Matters in the Sky

If the nose is too low, the shuttle picks up way too much speed and the friction melts the airframe. If the nose is too high, the shuttle doesn't have enough control and might tumble. By hitting the air at that steep angle, the flat underside of the shuttle acts as a giant brake. This is where the space shuttle re entry gets visually insane. A layer of ionized gas, or plasma, wraps around the vehicle. This plasma is so dense it actually blocks radio waves. For about 12 minutes, the crew is in total "mission control silence." They are alone in a fireball.

Surviving the 3,000-degree plasma envelope

The heat is the main character here. We’re talking $3,000^\circ\text{F}$ on the leading edges of the wings. To survive this, NASA didn't use metal. Metal melts. Instead, they used over 24,000 individual Silica tiles. Honestly, these tiles are weird. They are mostly air—90% air, actually—and they’re so good at shedding heat that you could hold one by the corner while the center is glowing red hot.

But they were fragile. They felt like brittle Styrofoam.

During the STS-107 mission, a piece of foam from the external tank hit the left wing during launch. It punched a hole in the Reinforced Carbon-Carbon (RCC) panels. When the Columbia began its space shuttle re entry on February 1, 2003, that superheated plasma didn't just stay on the outside. It snaked into the wing. It melted the aluminum structure from the inside out. This tragedy changed how NASA viewed "minor" launch damage forever. It proved that during re-entry, there is zero margin for error. None.

👉 See also: Finding a macOS Catalina Download That Actually Works (and Why It’s Still Worth It)

The "S-Turns" and energy management

Once the shuttle drops below about 150,000 feet, it stops being a spacecraft and starts trying to be an airplane. Sort of. Since it has no engine power at this point, it’s a "dead stick" landing. You get one shot. If you’re too high or too fast when you reach the runway at Kennedy Space Center, you can’t just "go around."

To bleed off all that excess speed, the pilots perform four massive S-turns.

Imagine a giant slalom skier on a mountain. These steep banks, sometimes up to 80 degrees, use the atmosphere to scrub off velocity. If you’ve ever wondered why the shuttle took such a curvy path on the radar, that’s it. They were basically throwing the ship into side-slips to make sure they didn't overspeed the runway. By the time they hit the "HAC" or Heading Alignment Circle, they’ve slowed down from 17,000 mph to just a few hundred.

What most people get wrong about the landing

People see the landing gear come down and think the hard part is over. It’s not. Most commercial airliners land at around 150 mph. The space shuttle hit the tarmac at 225 mph. That’s why you see that massive drag parachute deploy from the tail—without it, the brakes would likely catch fire or the tires would disintegrate.

📖 Related: Why Meters Per Second Squared Is the Most Misunderstood Unit in Physics

- The tires were filled with nitrogen, not air, to handle the pressure changes.

- The landing gear was deployed by gravity and pyrotechnics because hydraulic pumps were too risky to rely on at that stage.

- The pilots only had about 15 seconds of "flare" time to level out the ship before touchdown.

It was a manual process. While the computers (which, by the way, had less processing power than a modern toaster) did most of the heavy lifting during the plasma phase, the final touchdown was a feat of human piloting. Commanders like Eileen Collins or Charlie Bolden had to feel the ship's weight and drag to stick the landing.

Moving beyond the Shuttle era

The space shuttle re entry was a technological marvel, but it was also incredibly expensive and, let's be real, risky. Today, we see SpaceX’s Dragon or Boeing’s Starliner using capsules instead of winged gliders. Capsules are "statically stable." They want to fall heat-shield first. It’s a much safer way to come home because you don't have to worry about wing structures or complex aerodynamics.

However, we lost something when the shuttles retired in 2011. We lost the ability to bring back massive amounts of cargo or satellites from orbit and land them gently on a runway.

Actionable Insights for Space Enthusiasts

If you want to truly understand the physics of how we get back from space, start by looking at the "Entry Interface." This is the imaginary line at 400,000 feet where the air becomes thick enough to matter. You can track current re-entry paths for the ISS or Starship test flights via sites like Heavens-Above or the Space-Track database.

Understanding the "Heat Shield" isn't just about high-tech ceramics; it's about the "Ablative" versus "Reusable" debate. While the shuttle used reusable tiles, most modern craft use ablative shields that slowly burn away to carry heat with them. If you’re ever at the Kennedy Space Center or the Udvar-Hazy Center, look at the underside of Discovery. You’ll see the scars—the discolorations and the tiny pits in the tiles. Those aren't defects. They are the physical evidence of a vehicle that survived a 3,000-degree blowtorch while falling from the stars.

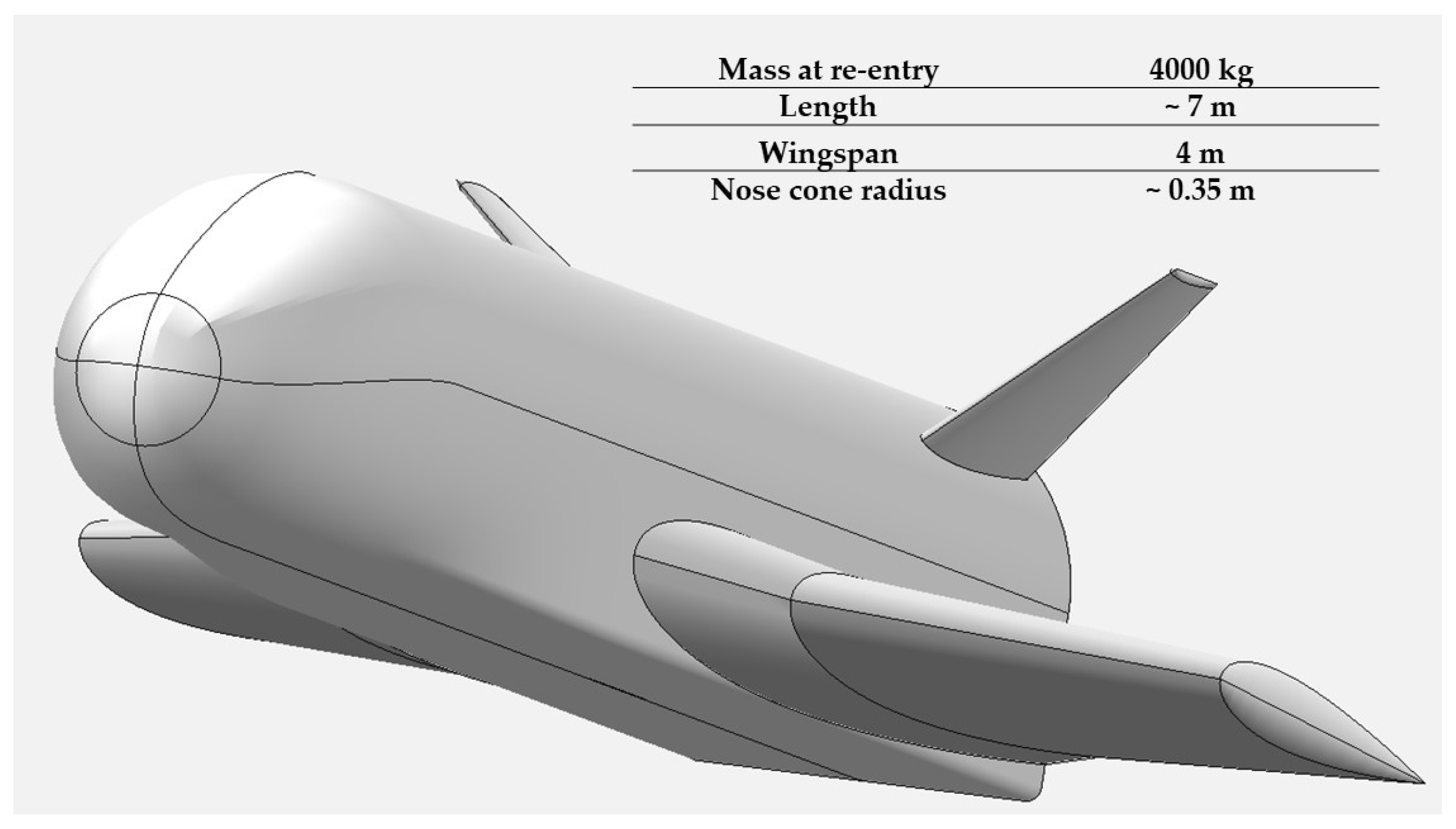

To keep up with how the next generation handles this, watch the upcoming Sierra Space "Dream Chaser" missions. It’s a new winged spaceplane that’s basically the spiritual successor to the shuttle, designed to land on runways but with modern, more durable thermal protection systems that don't require the thousands of hours of manual labor the old shuttle tiles did.