If you look at a grainy photo of Buzz Aldrin on the moon, it feels triumphant. It’s clean. It’s heroic. But if you open a newspaper from 1961, the vibe was totally different. It was frantic. People were actually terrified. Most of that raw, unfiltered anxiety didn't end up in the official NASA archives; it lived in the space race political cartoons found in the back pages of the Washington Post or the Soviet Pravda. These drawings weren't just funny sketches. They were psychological warfare.

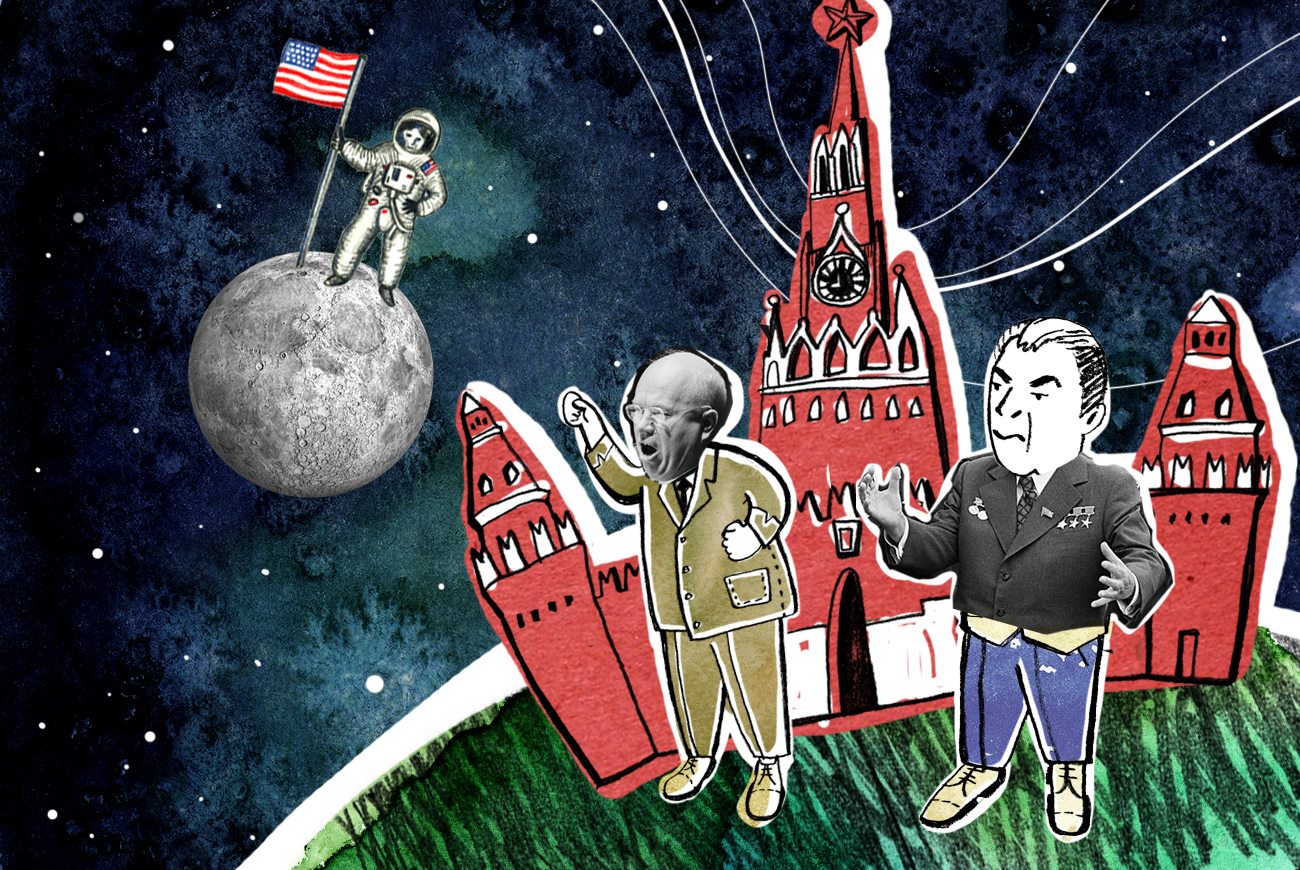

Cartoons from that era functioned like the Twitter memes of the Cold War. They moved fast. They hit hard. While politicians gave long-winded speeches about the "New Frontier," cartoonists like Herbert Block (Herblock) or Bill Mauldin were busy drawing Uncle Sam as a bumbling turtle or Nikita Khrushchev as a sweaty gambler.

The Sputnik Shock and the "Sleepy American" Myth

When the USSR launched Sputnik 1 in October 1957, the American psyche didn't just crack—it shattered. The media response was immediate and brutal. You’ve probably heard that America was unified in its desire to catch up. Honestly? That's a bit of a rewrite. The space race political cartoons from late '57 show a country that was mostly just mad at itself.

Herblock, a legend at the Washington Post, drew a famous piece showing a sleeping Eisenhower while a Soviet beeping sphere zipped overhead. It wasn't about the technology. It was about perceived laziness. The cartoonists were basically accusing the administration of napping while the "Red Menace" took the high ground.

One particularly biting illustration from the era shows two Soviet scientists looking at a tiny Sputnik. The caption implies they don't have indoor plumbing, but they have a satellite. This became a recurring theme in Western propaganda: the idea that the USSR was a "Potemkin village" of high-tech toys built on the backs of a starving peasantry. It was a coping mechanism. If we couldn't be first, we could at least claim to be more civilized.

How the Soviets Flipped the Script

We don't talk enough about the Russian side of this. Soviet cartoonists like the Kukryniksy collective or Boris Efimov were incredibly skilled. Their space race political cartoons weren't just about winning; they were about mocking American capitalism.

In Krokodil (the Soviet version of Punch or The New Yorker), they frequently depicted the U.S. space program as being run by Nazis. They weren't entirely wrong—Operation Paperclip was a real thing, and Wernher von Braun was a former SS officer. Soviet cartoons would show von Braun in a lab coat with a swastika shadow behind him, trying to build a rocket that kept exploding because it was built for profit, not for "the people."

✨ Don't miss: Who Has Trump Pardoned So Far: What Really Happened with the 47th President's List

The contrast was sharp. Soviet imagery was clean, socialist-realist, and focused on the "New Soviet Man." American imagery was often self-deprecating, messy, and focused on the tax burden.

The Cost of the Moon: A Hard Pivot in the Late 60s

By 1967, the tone changed. The "fun" was gone.

The Apollo 1 fire killed three astronauts. The Vietnam War was hemorrhaging money. Suddenly, space race political cartoons started asking a very uncomfortable question: "Why are we going to the moon when Detroit is burning?"

There’s a famous cartoon by Paul Conrad that shows a massive Saturn V rocket taking off, but the flame from the engines is burning a hole through a map of the United States, specifically over impoverished inner cities. It’s heavy. It’s not subtle. It reflects the 1969 Harris poll that showed over half of Americans actually didn't think the moon landing was worth the cost. That’s a stat that usually gets buried in the nostalgia.

Why These Drawings Rankle Historians Today

Historians like Roger Launius, the former NASA Chief Historian, often point out that these cartoons are more accurate than official press releases. Why? Because they capture the controversy.

We like to think of the 60s as this era of "One Giant Leap" unity. It wasn't. It was a decade of intense domestic friction.

🔗 Read more: Why the 2013 Moore Oklahoma Tornado Changed Everything We Knew About Survival

- The Civil Rights Connection: Cartoonists in the Black press, like those for the Chicago Defender, often drew the moon as a gated community. One cartoon showed a white man planting a flag on the moon while a Black man in a slum couldn't even get a loan for a house.

- The Gender Gap: Women were almost entirely absent from these cartoons unless they were portrayed as "worried wives" waiting at home. It wasn't until much later that the media acknowledged the "Hidden Figures" behind the math.

- The "Nazi" Factor: British cartoonists were particularly obsessed with the fact that both sides were using German scientists. They’d draw rockets with "Made in Germany" stickers on the side, mocking the idea of national superiority.

The Visual Language of the Cold War

Technically, these artists were doing something incredible. They had to simplify complex orbital mechanics into a single frame.

They used specific visual shorthand. The moon wasn't just a rock; it was a trophy. The stars weren't points of light; they were a chessboard. If you see a cartoon from 1962 with a giant clock, it’s a reference to the "missile gap"—the fake idea that the Soviets had way more nukes than the U.S.

Khrushchev was usually drawn as short, round, and explosive. JFK was drawn with an exaggerated shock of hair and a rocking chair. These caricatures helped the public digest the terrifying possibility of nuclear annihilation by making the players look like characters in a Sunday comic strip.

What We Get Wrong About the "Win"

Most people think the cartoons stopped once Armstrong stepped off the ladder. They didn't.

Post-1969 space race political cartoons are actually some of the most cynical. They show Uncle Sam standing on the moon, looking back at Earth and saying, "Now what?" The "victory" felt hollow to many because the problems at home hadn't moved. The cartoons shifted from "We must beat them" to "We beat them, and we're still broke."

It’s a reminder that technology never exists in a vacuum. It’s always tied to the dirt and the blood and the taxes of the people on the ground.

💡 You might also like: Ethics in the News: What Most People Get Wrong

Actionable Insights for History Buffs and Collectors

If you're looking to dive deeper into this world, don't just look at the famous ones. The real gold is in the regional papers.

How to Analyze a Space Race Cartoon:

- Identify the "Boogeyman": Is the artist more afraid of the Soviets or the US government's spending?

- Look for the German connection: Is there a subtle nod to the V-2 rocket origins? This shows the artist's level of cynicism.

- Check the date against the headlines: A cartoon from the week of the Cuban Missile Crisis will have a much darker tone than one from the launch of Telstar.

Where to find authentic archives:

The Library of Congress has a massive digital collection of Herblock’s work. It’s free. It’s high-res. You can see the actual ink bleeds. Also, check out the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum at Ohio State. They have the largest collection of funny-page history in the world.

Start your own digital collection:

Use the ProQuest Historical Newspapers database if you have library access. Search specifically for "editorial cartoons" between 1957 and 1975. You'll find things that haven't been reprinted in textbooks in fifty years.

Understanding space race political cartoons isn't just about art history. It's about realizing that even during our most "inspiring" moments, we were argued, divided, and deeply human. The moon was a goal, but the cartoons remind us that the struggle was always down here.

Next Steps for Your Research

- Visit the Library of Congress Online Gallery: Search for "Herbert Block" and filter by the years 1957–1969 to see the evolution of his "Sputnik" character.

- Compare International Perspectives: Find a digital archive of Krokodil magazine. Even if you don't speak Russian, the visual metaphors of the "Capitalist Shark" in space are easy to decode.

- Analyze Local Context: Use a tool like Newspapers.com to find how your specific city’s paper reacted to the Apollo 11 landing. You might be surprised to find that the local editorial was more concerned about a local pothole than the lunar module.

By looking at the margins of the newspaper, you get the real story of the 1960s—not just the one NASA wants you to remember.