Maps are supposed to be objective. You look at a line, and that's where one country ends and another begins. But when you start digging into maps of South Sudan, that comfortable certainty basically evaporates. Since the country gained independence from Sudan in 2011, cartographers have been sweating over where to draw the borders, and honestly, many of the digital maps you see on your phone are just plain wrong or, at the very least, incomplete.

It’s the world’s youngest nation. That sounds poetic, but for a mapmaker, it’s a nightmare. Borders in this part of the world aren't just lines on a screen; they are deeply contested zones involving oil, grazing rights, and decades of bitter conflict. If you’re planning to travel there or you're just a geography nerd trying to understand the Horn of Africa, you’ve got to realize that a standard Google Maps view only tells about sixty percent of the actual story.

The Abyei Headache and the Dotted Line

The biggest "uh-oh" on most maps of South Sudan is the Abyei Area. Look at any reputable map—say, from the UN or the CIA World Factbook—and you’ll see a weird little rectangle at the top of the country that is usually shaded differently or outlined with a dashed line. This is the Abyei Administrative Area. Both Sudan and South Sudan claim it.

Why? Oil. And cows.

The Ngok Dinka people live there, but the Misseriya Arab nomads migrate through it every year. It’s a mess of overlapping jurisdictions. Most digital maps just pick a side or use a generic "disputed" label, but that doesn't capture the reality on the ground. When you're looking at these maps, you aren't just looking at geography; you're looking at an ongoing peace negotiation that hasn't quite crossed the finish line. There are other spots too, like the Ilemi Triangle down south near Kenya, which has been a "maybe" zone for over a century.

💡 You might also like: Where to Stay in Seoul: What Most People Get Wrong

Why Your GPS Might Fail You in Juba

Let’s talk about infrastructure. If you open a map of South Sudan expecting to find a grid of paved highways, you’re in for a shock. Outside of the capital, Juba, and a few key corridors like the road to Nimule on the Ugandan border, "roads" are often just dirt tracks that turn into impassable swamps during the rainy season.

A map might show a solid red line indicating a primary road. In reality? That road might be a series of deep craters that can swallow a Land Cruiser whole. This is why specialized logistical maps from organizations like the World Food Programme (WFP) or Logistics Cluster are way more valuable than anything you’ll find in a standard atlas. They track seasonal accessibility. They tell you if a bridge is actually there or if it washed away in 2022.

The State Shuffle: 10, 28, or 32?

Politics changes the map faster than geography does. Between 2015 and 2020, the internal borders of South Sudan were a total moving target. President Salva Kiir increased the number of states from 10 to 28, then to 32, and then finally back to 10 (plus three administrative areas) as part of a peace deal.

If you are looking at an old map of South Sudan from 2018, it’s basically a historical artifact. It won't match the current administrative reality. The current 10-state model is what you’ll find on official UN OCHA (Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs) documents. These are the folks who actually produce the most "human-quality" maps because they need them for survival, not just for clicks.

📖 Related: Red Bank Battlefield Park: Why This Small Jersey Bluff Actually Changed the Revolution

The states you should see on a modern map are:

- Northern Bahr el Ghazal

- Western Bahr el Ghazal

- Lakes

- Warrap

- Western Equatoria

- Central Equatoria (where Juba sits)

- Eastern Equatoria

- Jonglei

- Unity

- Upper Nile

And don't forget the "Special Administrative Areas": Abyei, Pibor, and Ruweng. If your map doesn't show Ruweng as a distinct entity, it’s out of date.

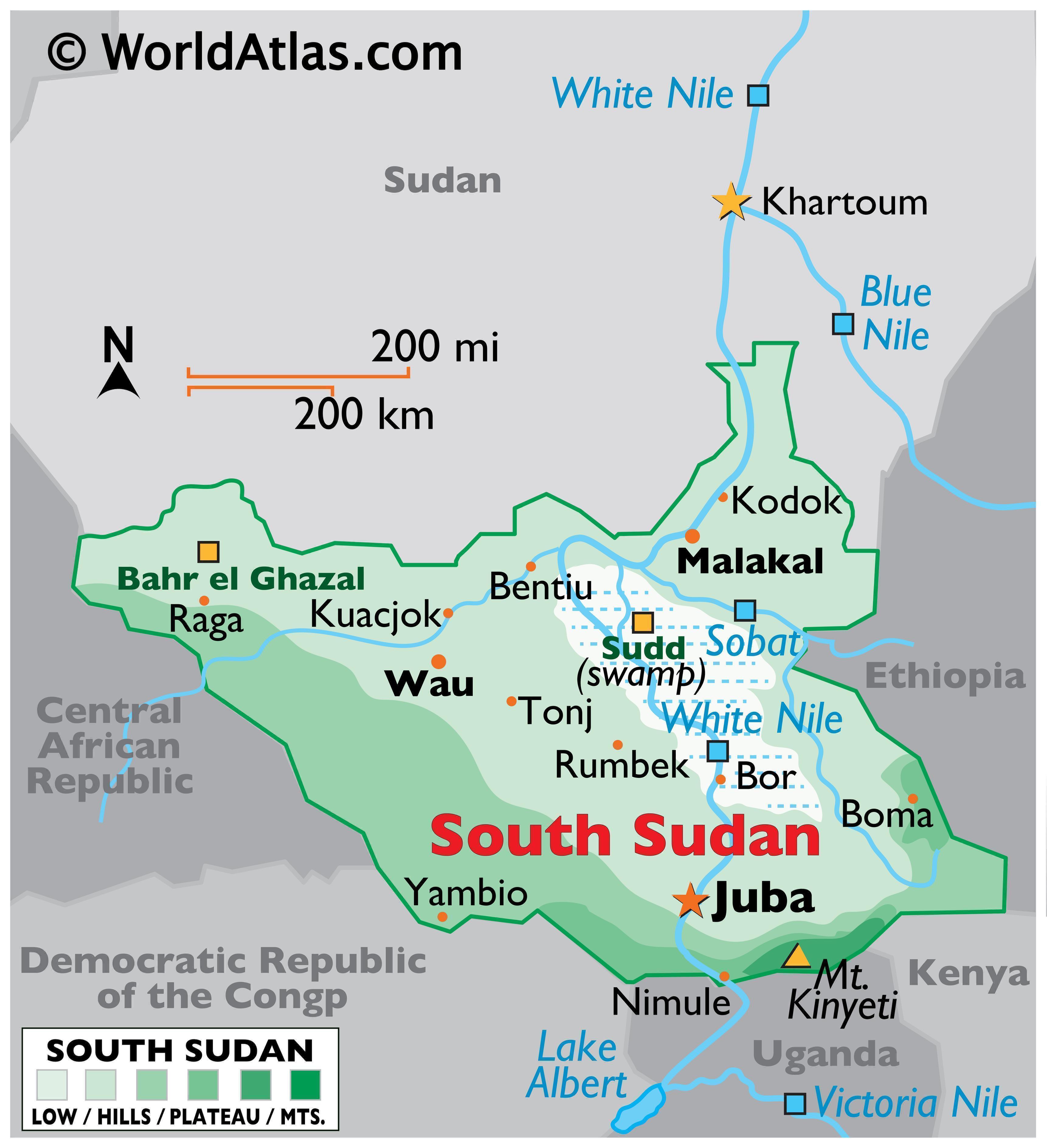

Topography and the Sudd: A Map of Water

South Sudan isn't just a flat savannah. One of the coolest—and most difficult to map—features is the Sudd. It’s one of the largest wetlands in the world. Imagine a swamp the size of England.

Satellite imagery struggles here because the "land" is constantly shifting. Floating islands of papyrus move around. Channels open and close. On a map, it looks like a big green blob in the center of the country, but for the people living there, the geography is fluid. If you're looking at maps of South Sudan for ecological reasons, you need to look at seasonal flood pulse maps. These show how the White Nile expands and contracts. In recent years, historic flooding has permanently altered the map, displacing hundreds of thousands and turning former grasslands into permanent lakes.

👉 See also: Why the Map of Colorado USA Is Way More Complicated Than a Simple Rectangle

Finding Reliable Data Sources

So, where do you actually get a good map? Don't just trust a random image search.

- UN OCHA South Sudan: This is the gold standard. They release PDF maps that are updated frequently with names of "payams" (sub-districts) and "bomas" (villages) that you won't find anywhere else.

- OpenStreetMap (OSM): Because it's crowdsourced, OSM often has better data on local clinics, markets, and water points in Juba than Google does. Humanitarian mappers often do "mapathons" to trace huts and roads from satellite imagery.

- South Sudan National Bureau of Statistics: They hold the official records, though their website can be a bit hit-or-miss depending on the server status in Juba.

The Human Element of the Map

A map is more than just coordinates. In South Sudan, names of places carry weight. Some towns have multiple names depending on which language group you’re talking to. A map created by an international NGO might use a colonial-era name or a misspelled Dinka or Nuer word.

When you look at the Boma Plateau or the Imatong Mountains, you’re looking at biodiversity hotspots that are barely charted. Mount Kinyeti is the highest point in the country, sitting at 3,187 meters. It's tucked away on the border with Uganda, and very few people have actually mapped its trails in detail. It’s wild. It’s rugged. And your standard topographic map probably misses the nuance of its microclimates.

The reality of South Sudan is that it is a country in flux. The maps are trying to keep up with a nation that is still defining itself. Whether it’s the disputed oil fields of Heglig or the shifting banks of the Sobat River, the lines are often blurred.

Actionable Insights for Using South Sudan Maps:

- Check the Date: If the map was made before 2020, the internal state borders are almost certainly wrong. Look for the "10 states + 3 areas" configuration.

- Verify Road Status: Never assume a "primary road" is paved. Cross-reference with the WFP Logistics Cluster "Physical Road Conditions" maps, which are updated weekly.

- Acknowledge the Dashed Lines: Understand that borders like Abyei and the Ilemi Triangle are legally "undetermined." Using a map that shows a hard line can actually be seen as a political statement in certain contexts.

- Use Offline Tools: If you're actually heading to the region, download Map.me or organic maps data based on OpenStreetMap. Cell service is non-existent once you leave the main hubs, and you’ll need those cached tiles.

- Look for P-Codes: If you are doing professional or academic work, use "Place Codes" (P-codes) provided by the UN. Names are spelled a dozen different ways (is it Bentiu or Bantiu?), but P-codes stay constant.

The map of South Sudan is a living document. It changes with the seasons and the politics. To understand it, you have to look past the static lines and see the movement of the water and the people.