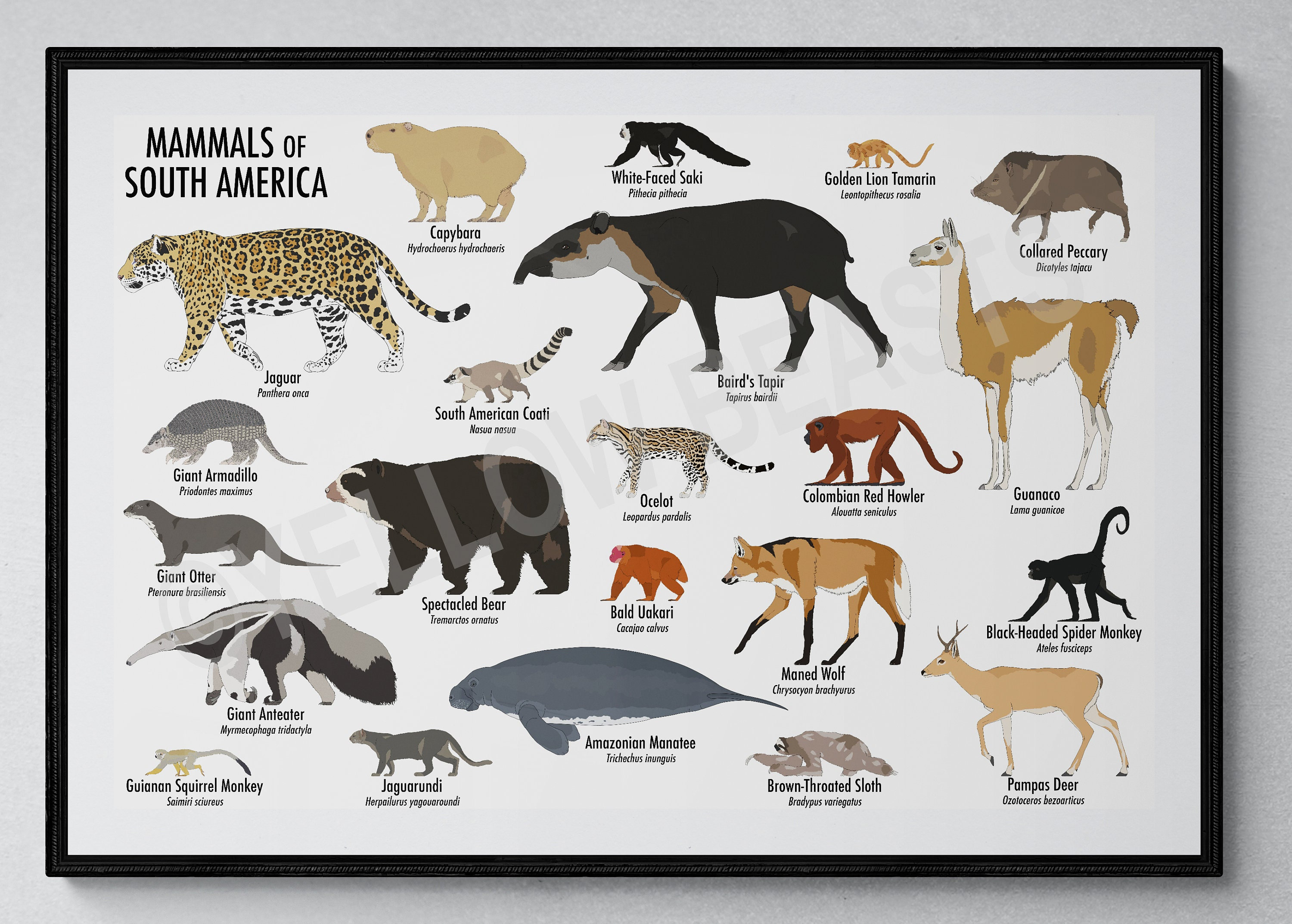

You’ve probably seen the posters. The ones with the jaguars staring intensely through a jungle canopy or a llama posing against the backdrop of Machu Picchu. It’s the classic imagery of South America mammals, but honestly, it barely scratches the surface of how weird things actually get down there. Most people think of South America as just "more Africa" but with different trees. It’s not. Not even close. While Africa’s wildlife is defined by massive herds of ungulates and huge prides of lions, South America is a land of oddities, survivors, and evolutionary experiments that stayed isolated for millions of years.

Think about the giant anteater. It looks like someone tried to design a vacuum cleaner using only scrap leather and fur. It has no teeth. None. It uses a two-foot-long tongue coated in sticky saliva to lick up 30,000 ants a day. If that isn't strange enough, consider the pink river dolphin of the Amazon. It’s not just a "color variant." These things have unfused neck vertebrae, allowing them to turn their heads 90 degrees to navigate through submerged tree branches during the flood season. You won’t find that in the ocean.

Why the History of South America Mammals is Actually a Thriller

To understand why these animals look the way they do, you have to look at the "Great American Biotic Interchange." For about 60 million years, South America was an island continent, much like Australia is today. Evolution went nuts. We had giant ground sloths the size of elephants and "terror birds" that would have easily swallowed a toddler. Then, around three million years ago, the Isthmus of Panama rose up.

It was a total takeover. Northern species like bears, cats, and camels (yes, llamas are basically mountain camels) rushed south. Many of the native South American lineages just couldn't compete and went extinct. The survivors are what we see today—a mix of ancient island weirdos and northern invaders that adapted to the tropics.

The Jaguar: More Than Just a Spotted Cat

The jaguar is the undisputed heavyweight champion of the Neotropics. But calling it a "leopard with a different pattern" is a massive disservice. It’s the third-largest feline globally, but it has the strongest bite force of any cat relative to its size. While a lion or tiger usually goes for the throat to suffocate prey, a jaguar often just crunches through the skull. They are aquatic. They love the water. I’ve seen footage of jaguars diving into rivers to wrestle caimans—and winning.

They are the apex of South America mammals, yet they are incredibly elusive. If you’re heading to the Pantanal in Brazil to find one, don’t expect a safari park experience. It’s hot, it’s buggy, and the jaguars move like ghosts through the hyacinth. Researchers like Dr. Alan Rabinowitz, who was instrumental in creating the world’s first jaguar preserve in Belize, often pointed out that these cats aren't just predators; they are "umbrella species." Protect the jaguar, and you accidentally protect everything else in the food chain.

👉 See also: 3000 Yen to USD: What Your Money Actually Buys in Japan Today

The High-Altitude Specialists

If you head to the Andes, the vibe changes completely. It’s thin air and freezing nights. Here, the camelids rule. You’ve got the domestic duo—llamas and alpacas—and their wild ancestors, the guanacos and vicuñas.

Vicuñas are fascinating. Their wool is the most expensive in the world because it’s incredibly fine and warm, a necessary adaptation for surviving at 15,000 feet. Back in the day, the Incas would round them up in massive ceremonies called Chaccu, shear them, and release them. They never killed them for the wool. It was a sustainable system hundreds of years before "sustainability" was a corporate buzzword. Today, those traditions are making a comeback in places like Lucanas, Peru, helping to save the species from the brink of extinction.

- Llamas: Big, sturdy, used for carrying gear.

- Alpacas: Smaller, fluffier, bred for that sweater-ready fleece.

- Guanacos: Wild, hardy, found from the Atacama Desert to Tierra del Fuego.

- Vicuñas: Delicate, protected, and producing gold-standard fiber.

The Amazon’s Secret Society

Deep in the rainforest, the canopy is where the real action is. Everyone knows about monkeys, but South American monkeys (Platyrrhines) are different from African or Asian ones. Most have prehensile tails. It’s basically a fifth limb.

Then there’s the sloth. Two-toed and three-toed varieties exist, and they are basically their own ecosystems. Their fur grows "backward" (from belly to back) because they spend so much time upside down; this allows rain to run off. They move so slowly that algae actually grows in their hair, giving them a greenish tint that helps them blend into the leaves. It's a slow-motion survival strategy that has worked for millions of years. Honestly, we could probably learn a thing or two about stress management from them.

The Maned Wolf: Not Actually a Wolf

The Cerrado, Brazil’s massive savanna, is home to one of the most misunderstood South America mammals: the maned wolf. It looks like a fox on stilts. It’s not a wolf, and it’s not a fox. It’s the only species in its genus, Chrysocyon.

✨ Don't miss: The Eloise Room at The Plaza: What Most People Get Wrong

These things are weirdly solitary. Unlike grey wolves that hunt in packs, maned wolves are loners. And get this—about 50% of their diet is fruit. Specifically, the "wolf apple" (Solanum lycocarpum), which actually helps them ward off kidney parasites. If you ever smell something in the Brazilian grasslands that smells exactly like marijuana, it’s probably maned wolf urine. It’s a well-documented phenomenon that has even led to police being called to zoos.

Capybaras and the Giant Otter

Water defines this continent. The Amazon, the Orinoco, the Paraná. Naturally, the mammals have leaned into it.

The capybara is the world’s largest rodent. It’s basically a 150-pound guinea pig that loves to swim. They are incredibly chill. You’ll see photos of birds, monkeys, and even small caimans sitting on them. But don’t let the "friend-shaped" meme fool you; they are wild animals and can be quite territorial when they have young.

On the flip side of the "cute" coin is the giant river otter. In Brazil, they call them "water wolves." They can reach six feet in length and they hunt in organized family groups. They are loud, aggressive, and can take down a caiman. If you see them while kayaking, keep your distance. They are curious but fiercely protective of their holts.

How to Actually See These Animals

If you’re serious about seeing South America mammals in the wild, you have to be smart about your timing and location. This isn't a trip you just wing.

🔗 Read more: TSA PreCheck Look Up Number: What Most People Get Wrong

- The Pantanal, Brazil: This is the best place on Earth for wildlife viewing. Because it’s a massive floodplain with open spaces, you can actually see the animals, unlike in the dense Amazon where everything is hidden behind a wall of green. Visit between July and October.

- The Galápagos, Ecuador: For sea lions and fur seals, this is a no-brainer. The animals here have no natural fear of humans, which is a surreal experience.

- Torres del Paine, Chile: Go here for pumas. Thanks to strict protections, the puma population in southern Chile has rebounded, and they are becoming much easier to spot against the granite peaks.

- Madidi National Park, Bolivia: One of the most biodiverse spots on the planet. It’s rugged and tough to get to, but it’s the real deal.

Realities of Conservation

It’s not all pretty pictures. Habitat loss is a massive issue. The Atlantic Forest, for example, has been reduced to about 12% of its original size. Species like the Golden Lion Tamarin were almost wiped out entirely.

However, there is hope. Organizations like the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute and local NGOs are doing incredible work with reforestation and "wildlife corridors." These corridors allow isolated populations of animals to meet and breed, keeping the gene pool healthy. Without these bridges of forest, a population of monkeys might be trapped in a tiny "island" of trees, destined for inbreeding and extinction.

Actionable Insights for the Ethical Traveler

If you want to support these animals and see them responsibly, here is what you need to do. First, avoid "pay-to-pet" operations. If a place allows you to hold a sloth or a jaguar cub for a photo, it’s not a sanctuary; it’s an exploitation business. These animals are often snatched from the wild or kept in abysmal conditions.

Instead, look for lodges that are "Global Sustainable Tourism Council" (GSTC) certified. Use local guides. Not only do they have the "jungle eyes" to spot a camouflaged pygmy marmoset, but your money goes directly into the local economy, providing a financial incentive for communities to protect the forest rather than clear-cut it for cattle.

Lastly, manage your expectations. South America is not a zoo. You might spend four days in the rain looking for an anteater and only see a bunch of very interesting squirrels. But when you finally see that flash of a spotted tail or hear the haunting howl of a red howler monkey at 5:00 AM, it makes the wait worth it.

Respect the distance. Use a long lens. Bring better bug spray than you think you need. The mammals of this continent are a living link to a prehistoric world, and seeing them on their own terms is one of the most rewarding things you can do on this planet.

Stay curious. Keep your eyes on the treeline. The more you look, the more South America reveals its secrets. There is always something moving in the shadows.