Standing in a stadium when the brass band kicks in is something else. You’ve got sixty thousand people suddenly finding the same key, or trying to, and the air just vibrates. But then the language shifts. If you aren't from around here, or even if you are, the transition from isiXhosa to Sesotho to Afrikaans can feel like a linguistic obstacle course. The South African national anthem words aren't just a song; they’re a five-language mashup that tells the story of a country trying to fix itself in real-time.

It’s messy. It’s beautiful. It’s also incredibly easy to mumble through if you don't know your Maluphakanyiswe from your Uit die blou.

Honestly, most people get the order wrong. They think it’s just a random collection of verses tossed together to keep everyone happy after 1994. It kind of was. But there’s a specific logic to how these lyrics function as a "bridge" between a dark past and a hopeful, if complicated, present.

The Frankenstein’s Monster of Music

Most national anthems are written by one person during a single moment of patriotic fervor. Think Francis Scott Key watching bombs over Baltimore. South Africa didn’t do that. We took two entirely different songs—one a prayer for Africa and the other a call to the soil—and welded them together with a blowtorch.

The first half comes from Nkosi Sikelel' iAfrika (God Bless Africa). It was composed back in 1897 by Enoch Sontonga. He was a teacher at a Methodist mission school. Originally, it was a hymn. A quiet, soulful plea for divine intervention. By 1925, it had become the defiant anthem of the African National Congress (ANC) and a global symbol of the anti-apartheid struggle.

Then you have Die Stem van Suid-Afrika (The Call of South Africa).

This one was written by C.J. Langenhoven in 1918. For decades, it was the official anthem of the apartheid government. To many Black South Africans, those words represented the very boots that were pressing down on them. So, when Nelson Mandela took office, he had a massive problem. How do you keep the peace? You can’t just scrap Die Stem without terrifying the white minority, and you can’t ignore Nkosi Sikelel' iAfrika after people died singing it in the streets.

🔗 Read more: Dr Dennis Gross C+ Collagen Brighten Firm Vitamin C Serum Explained (Simply)

The solution was a compromise that looks weird on paper but sounds like magic in a choir. In 1997, the version we know today was shortened and combined into a single piece of music. It doesn't repeat. It just evolves.

Getting the South African national anthem words right

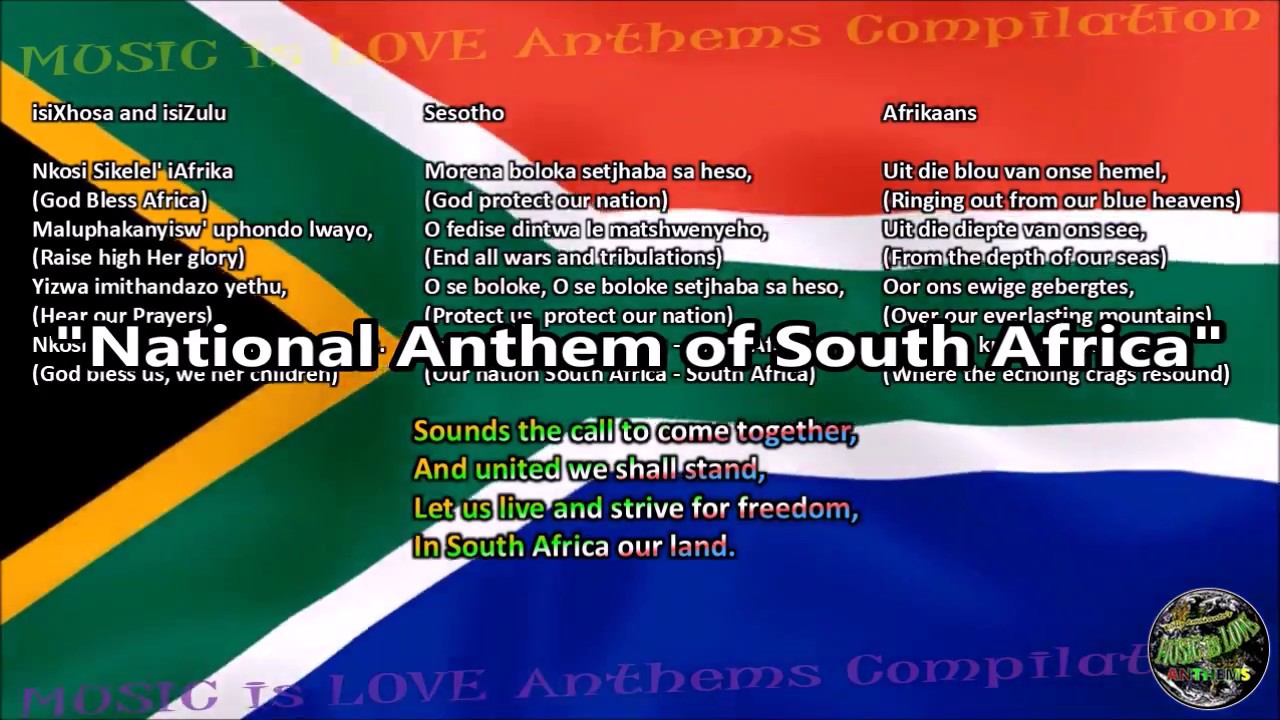

If you’re trying to actually sing the thing without looking like a "lip-syncher" on TV, you have to navigate five languages: isiXhosa, isiZulu, Sesotho, Afrikaans, and English.

Here is the breakdown of what is actually being said.

The opening starts in isiXhosa:

Nkosi sikelel' iAfrika (Lord bless Africa)

Maluphakanyiswe uphondo lwayo (May her glory be lifted high)

Then it slides into isiZulu:

Yizwa imithandazo yethu (Hear our petitions)

Nkosi sikelela, thina lusapho lwayo (Lord bless us, your children)

People often trip up on the transition to Sesotho. It happens fast.

Morena boloka setjhaba sa heso (Lord we ask You to protect our nation)

O fedise dintwa le matshwenyeho (Intervene and end all conflicts)

O se boloke, O se boloke setjhaba sa heso (Protect us, protect our nation)

Setjhaba sa South Afrika - South Afrika (The nation of South Africa)

💡 You might also like: Double Sided Ribbon Satin: Why the Pro Crafters Always Reach for the Good Stuff

Then comes the shift that still gives some people chills and others pause. The tempo picks up. The key changes. We enter the Afrikaans section, taken from the old anthem:

Uit die blou van onse hemel (From the blue of our heavens)

Uit die diepte van ons see (From the depths of our sea)

Oor ons ewige geberghtes (Over our everlasting mountains)

Waar die kranse antwoord gee (Where the echoing crags resound)

Finally, it ends in English. It’s a bit of a grand finale, focusing on unity:

Sounds the call to come together

And united we shall stand

Let us live and strive for freedom

In South Africa our land

Why the order actually matters

There’s a reason the isiXhosa and isiZulu verses come first. It acknowledges the oldest roots and the majority voice. But by ending in English—a "neutral" global language in this context—the song attempts to pull every disparate group into a single room.

It’s a linguistic handshake.

Some critics, like those from the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF), have argued for years that the Afrikaans section should be removed. They see it as a "stain" of the colonial past. On the flip side, many argue that removing it would break the "Kempton Park" spirit of the 1990s—the idea that everyone has a place in the new South Africa, even those who were once the oppressors.

It’s a tense balance. Every time the anthem is played at a Springbok rugby match, you can see this tension playing out. You’ll see a massive Afrikaner guy singing the Xhosa parts with tears in his eyes, and you’ll see young Black students singing the Afrikaans parts because it’s the only country they’ve ever known. It’s complicated. It’s South African.

📖 Related: Dining room layout ideas that actually work for real life

Common Mistakes and How to Avoid Them

If you're practicing, the "Maluphakanyiswe" part is where most people mumble. It’s a mouthful. Break it down: Ma-lu-pha-ka-nyi-swe.

Another big mistake? The "South Afrika" part at the end of the Sesotho section. People tend to sing it like the English "South Africa," but the phonetics are different. It’s more clipped.

And for the love of everything, don't sing the whole of Die Stem. If you keep going after "antwoord gee," you’re singing the old version, and you're going to get some very side-eyed glances. The current version is a "compact" version. It’s designed to be finished in under two minutes.

The Technical Reality of the Music

Musically, the anthem is actually quite difficult to perform well because it starts as a hymn (4/4 time, slow, prayerful) and ends like a military march. This change in "time feel" is why many pop singers fail miserably when they try to do a "soulful" version at sports events. You can't really riff on it. It requires a steady, communal beat.

If you listen to the 1995 Rugby World Cup recording—the one that basically defined the post-apartheid era—the power didn't come from a soloist. It came from the fact that the players, who were mostly white Afrikaans speakers at the time, had spent weeks learning the Xhosa lyrics. That effort, that "ugly" singing by people who were clearly trying, meant more than a perfect vocal performance ever could.

Actionable Steps for Mastering the Lyrics

If you actually want to respect the song and the history behind it, don't just memorize the sounds. Understand the weight.

- Listen to the 1994 versions: Go back and find the early recordings where the transition was still new. You can hear the "seams" where the songs were joined.

- Practice the 'Clicks': In the isiXhosa and isiZulu sections, there aren't heavy "clicks" in the anthem words themselves, but the vowels are pure. Think "Ah, Eh, Ee, Oh, Oo." Avoid the "r" sounds that you’d find in American English.

- Focus on the 'Morena boloka' section: This is the emotional heart of the song for many. It’s a prayer for peace. If you get this right, the rest usually falls into place.

- Watch the Springboks sing it: Seriously. Watch the faces of players like Siya Kolisi or Eben Etzebeth. They aren't just singing; they are performing a ritual. Copy their phrasing.

The South African national anthem words are a living document. They are an agreement we make with each other every time we stand up. Whether you’re at a school assembly or a stadium in Johannesburg, knowing these words is a way of saying, "I see you, and I'm trying to hear you." It’s not about being a perfect singer. It’s about not mumbling through the parts you don't know.

Learn the syllables. Respect the history. Sing the compromise.