You’ve finally pulled it out. That crusty, mahogany-colored boule you spent three days nursing. It smells like a dream—tangy, yeasty, and warm. But when the serrated knife finally hits the cutting board, the interior reveals something you didn't expect. Maybe it's a dense brick. Maybe it has a giant cavern at the top and a gummy "glue line" at the bottom. This is where a sourdough bread crumb chart becomes your best friend, because, honestly, the crumb is a literal map of every single mistake or triumph you had during the process.

Most people think sourdough is just about the "open crumb." You know the ones—those Instagram photos where the bread is more air than dough. But here's the thing: a wide-open crumb isn't always the goal. If you're trying to spread butter on a slice and it falls through a hole the size of a golf ball, that’s a failure for toast. We need to look at what the holes are actually telling us about fermentation, temperature, and gluten.

💡 You might also like: White Linen Roman Shades: What Most People Get Wrong About Choosing Window Treatments

Reading the Sourdough Bread Crumb Chart Like a Pro

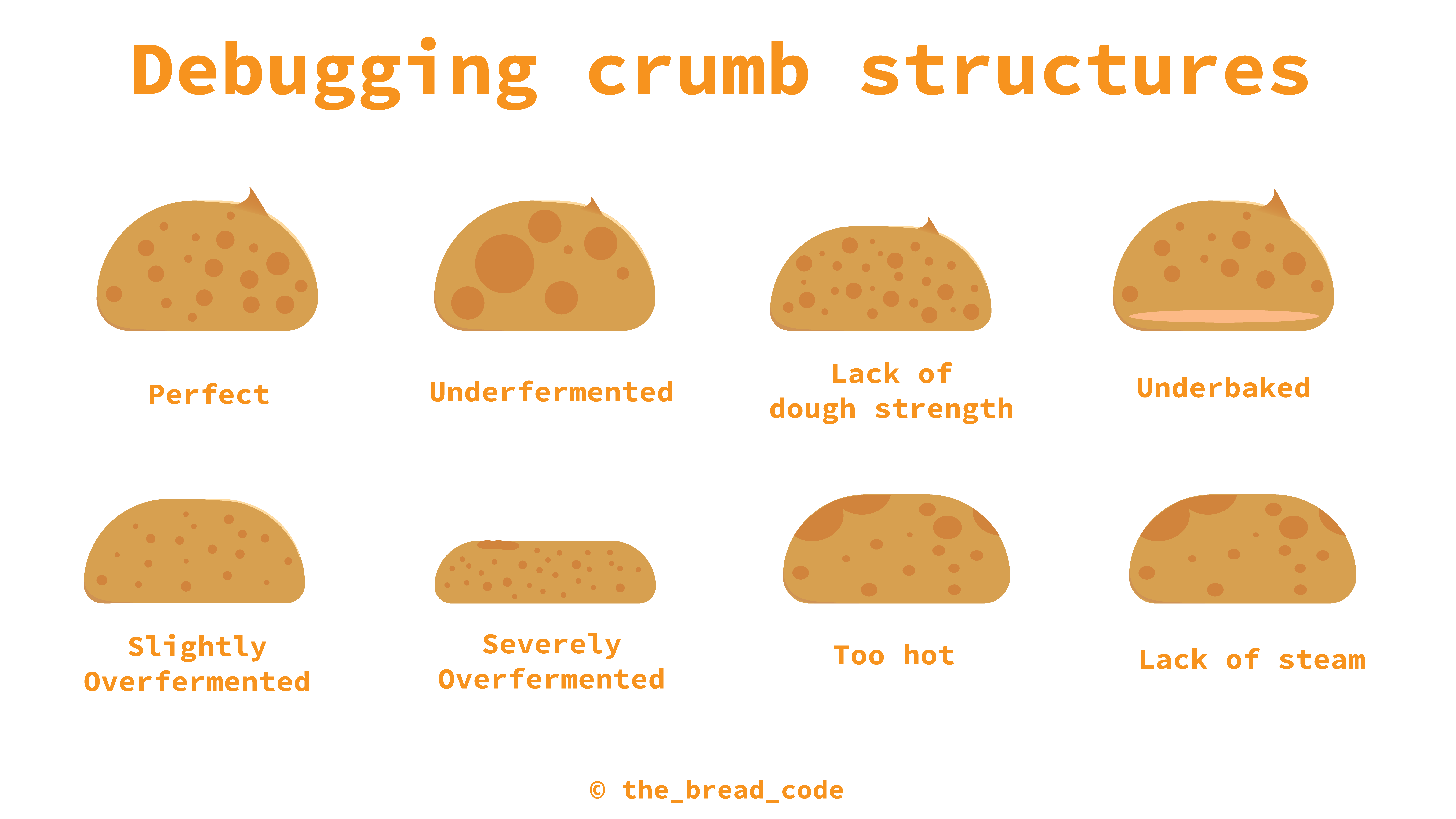

The crumb is a snapshot in time. It captures the exact moment the heat of the oven set the protein structure of your dough. When we talk about a sourdough bread crumb chart, we are basically categorizing the "alveoli"—the little gas pockets created by yeast and bacteria.

If you see tiny, uniform holes that look like a sandwich loaf from the grocery store, you’ve likely dealt with a "closed crumb." This usually happens because the hydration was too low or the dough was handled too roughly, popping all those delicate bubbles. It’s not "bad" bread. It's just dense. On the flip side, "fools crumb" is the great deceiver. This is when you see huge holes surrounded by dense, unfermented dough. It looks like you nailed it, but once you bite in, it's gummy. This happens when the dough goes into the oven underproofed. The yeast had a massive burst of energy (oven spring), but the overall structure wasn't ready to support it.

Then there is the overproofed loaf. This one is heartbreaking. You wait and wait, and then the loaf collapses in the oven. The crumb chart describes this as "shaggy" or "collapsed." The gluten essentially gave up. It's like a balloon that was blown up too far and then leaked. The holes are small, the bread is flat, and the flavor might be a bit too sour, almost like vinegar.

The Role of Hydration and Protein

You can't talk about crumb without talking about water.

Higher hydration (more water relative to flour) generally leads to a more open crumb. Water turns to steam. Steam expands. But if you're using a low-protein flour, like an all-purpose flour from a generic brand, it can't hold that steam. It’s like trying to build a skyscraper with toothpicks. You need the strength of bread flour or a high-protein whole wheat to trap those gases.

Expert bakers like Trevor J. Wilson, author of Open Crumb Mastery, often emphasize that it’s not just about adding more water. It’s about how you manage that water. You have to build "tension." If the skin of your dough isn't tight, the gas will just push the dough out sideways instead of up. This results in a wide, flat loaf with a "disorganized" crumb.

Temperature: The Silent Variable

Temperature is the "secret" ingredient that most beginners ignore. Most sourdough bread crumb chart examples show the results of fermentation at roughly 75°F to 80°F. If your kitchen is a chilly 65°F, your yeast is moving at a snail's pace. If you follow a recipe's timing exactly in a cold kitchen, you will end up with an underproofed loaf every single time.

I’ve seen it a thousand times. A baker follows a 4-hour bulk fermentation rule, but their kitchen is cold. They cut into the bread and see "tunneling"—massive holes at the top and a dense, "mealy" texture at the bottom. This is a classic underproofed signature. The gas collected in a few spots but didn't have time to saturate the whole loaf.

- Underproofed: Large, uneven "caverns" near the crust, dense base, gummy texture.

- Perfectly Proofed: Even distribution of holes, ranging from small to medium-large, translucent "walls" between the holes.

- Overproofed: Small, tight holes, flat profile, dull crust color.

The Impact of "Bulk Fermentation"

This is the most critical stage. Bulk fermentation is when the dough sits in a bowl and grows before you shape it. If you cut this short, no amount of "oven spring" will save you.

A good sourdough bread crumb chart will show you that "lacy" texture. That translucency in the crumb is a sign of well-developed gluten and proper fermentation. It means the starches were broken down correctly by the enzymes. If your crumb looks opaque and white, like chalk, it might be under-fermented.

The Myth of the "Perfect" Open Crumb

We need to be honest here. The obsession with a wildly open crumb is kinda weird.

For a long time, the "Tartine style" (popularized by Chad Robertson) was the gold standard. Everyone wanted those massive, irregular holes. But if you talk to professional bakers who actually eat their bread, many prefer a "moderately open" crumb. Why? Because it holds toppings. A sourdough bread crumb chart helps you dial in exactly what you want.

If you want a "sandwich" style crumb, you actually want to decrease hydration slightly and maybe add a touch of fat, like butter or olive oil. This softens the crumb and makes the holes smaller and more uniform. If you want that "artisan" look, you push the hydration up to 80% or 85% and handle the dough like it’s a fragile cloud.

Why Your Crumb is Gummy

Gummy bread is the worst. You spend 24 hours on a loaf only for it to feel like wet dough in your mouth. This usually comes down to two things: underbaking or cutting it too early.

You have to let sourdough cool completely. I know, it's hard. But the bread is still cooking when it comes out of the oven. The internal structure is setting. If you slice it while it's hot, the steam escapes too fast, and the starches collapse into a gummy mess. Also, check your internal temp. It should be at least 208°F (97°C-98°C) for a standard sourdough.

Practical Steps to Improve Your Crumb

Stop guessing. If you want to master the sourdough bread crumb chart, you have to be a bit of a scientist.

📖 Related: Why Use a 5.0 to 4.0 GPA Calculator: How to Actually Translate Your Weighted Grades

First, get a dedicated thermometer for your dough. Not just the room—the dough itself. Aim for a "final dough temperature" of 78°F. This gives you a predictable baseline.

Second, take photos. Every time you cut a loaf, take a picture of the crumb and look at your notes. Did you bulk ferment for 5 hours? 6? Was the dough jiggly? Did it have bubbles on the surface? Over time, you’ll start to see the patterns. You'll see that a 30-minute increase in bulk fermentation was the difference between "tunneling" and a "perfectly aerated" loaf.

Lastly, watch the "jiggle." When you're at the end of bulk fermentation, the dough should feel alive. It should shake like jello when you nudge the bowl. It should have visible bubbles on the sides and top. If it feels heavy and dead, it’s not ready.

Actionable Troubleshooting

If your crumb is consistently too tight, try increasing your hydration by 3-5%. If it's consistently "tunneling" with giant holes at the top, extend your bulk fermentation by 45 minutes. If your bread is flat and has no holes, you’re likely overproofing or your starter isn't strong enough.

Check your starter's health. It should be doubling or tripling within 4-6 hours of feeding. If it’s sluggish, your crumb will be too. A weak starter cannot produce the gas volume needed to create those beautiful alveoli shown in a sourdough bread crumb chart.

Start by changing only one variable at a time. If you change the flour, the water, and the timing all at once, you’ll never know which one fixed the problem. Pick one. Test it. Eat the results. Even the "failures" usually make pretty great croutons or bread pudding.

Get a clear glass container for your bulk fermentation. This lets you actually see the bubbles forming at the bottom and sides. It’s a game-changer for understanding when to move to the shaping phase. Stop relying on the clock—start relying on your eyes and the physical state of the dough.