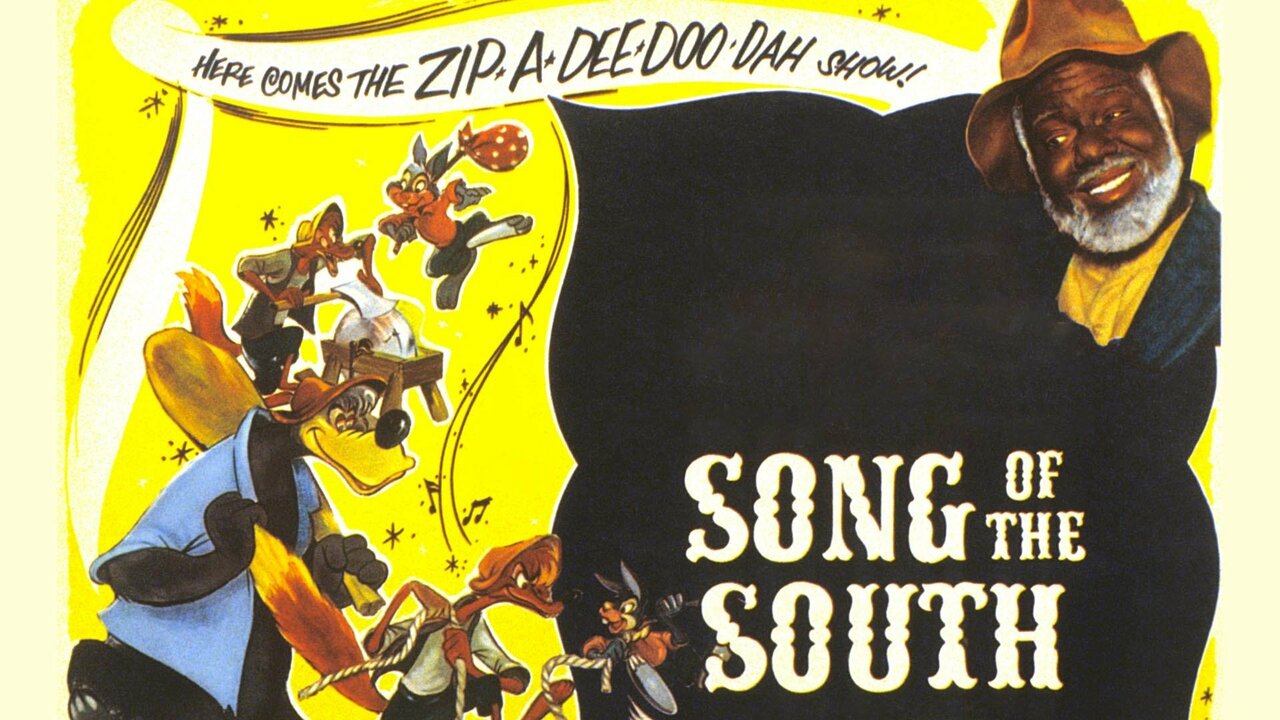

You probably know the tune. Even if you’ve never seen the 1946 film—and honestly, most people under forty haven't because Disney locked it in the vault decades ago—the songs from Song of the South are stuck in the collective DNA of American pop culture. It’s a strange, uncomfortable paradox. How can a movie be so controversial that it's effectively banned, while its music remains some of the most recognizable in history?

The reality is complicated. It's messy.

When people talk about this soundtrack, they usually stop at "Zip-A-Dee-Doo-Dah." But the musical landscape of the film, composed by a mix of Hollywood veterans and inspired by African American folk traditions, carries a weight that most Disney soundtracks just don't have. It’s a blend of high-production studio polish and deep-rooted Southern storytelling.

Why We Still Talk About These Melodies

Let's be real: Disney doesn't like talking about this movie. At all. Yet, for years, the company continued to use the songs from Song of the South in theme parks, parade floats, and "Sing-Along Songs" VHS tapes. This created a weird cultural vacuum. We grew up with the Bluebird on our shoulder without knowing the context of the man singing about it.

James Baskett, who played Uncle Remus, wasn't even allowed to attend the film's premiere in Atlanta because of Jim Crow laws. That's a gut-punch of a fact. It casts a long, dark shadow over the "Mister Bluebird's on my shoulder" vibe. The music was designed to evoke a "simpler time," but that simplicity was a total fiction of the Reconstruction-era South.

The Compositional Heavyweights

Behind the scenes, the music wasn't just some casual project. We are talking about Charles Wolcott, Allie Wrubel, and Ray Gilbert. Wrubel and Gilbert were the ones who penned the heavy hitter, "Zip-A-Dee-Doo-Dah." They won an Academy Award for it.

It’s catchy. It’s relentlessly upbeat. That’s why it worked.

But then you have songs like "Ev'rybody Has a Laughing Place" or "How Do You Do?" These tracks were meant to move the Br'er Rabbit segments along. They use a specific kind of rhythmic bounce that feels like a vaudeville act mixed with a Georgia porch session. It’s technically brilliant, which is exactly why it’s so hard to just "delete" from history.

Breaking Down the Key Tracks

The soundtrack consists of about nine primary numbers, depending on how you count the reprises. Some are orchestral, some are choral, and some are character-driven.

👉 See also: The Real Story Behind I Can Do Bad All by Myself: From Stage to Screen

Zip-A-Dee-Doo-Dah

This is the big one. It’s the anthem of the film. Influenced by the "Zip Coon" minstrel songs of the 19th century—a fact many musicologists point to with significant concern—the song was intended to show Uncle Remus's "contentment." Today, it’s mostly been scrubbed from the parks, replaced by The Princess and the Frog themes in the Splash Mountain (now Tiana’s Bayou Adventure) rebrand.

Ev'rybody Has a Laughing Place

This song is basically the blueprint for Disney "ride music." It’s repetitive, jaunty, and drives the plot toward the inevitable trap Br'er Fox sets. It features a lot of the "character voice" work that became a Disney staple.

Uncle Remus Said

Performed by the Hall Johnson Choir along with James Baskett. This one is fascinating because the Hall Johnson Choir was a legendary African American choral group known for preserving spirituals. Their inclusion was meant to lend "authenticity" to the film, but it ultimately serves a narrative that many find patronizing today.

So White, So Bright

A lesser-known track, often forgotten in the shadow of the animated segments. It’s more of a traditional 1940s film ballad. It feels dated in a way the animated songs don't.

The Hall Johnson Choir and Cultural Ownership

We need to talk about Hall Johnson. He was a pivotal figure in Black choral music. His involvement in the songs from Song of the South is often used as a shield by defenders of the film to say, "Look, it was a collaboration!"

But collaboration in 1946 wasn't equal.

Johnson’s arrangements are sophisticated. He took the "spiritual" sound and adapted it for the silver screen. If you listen closely to the harmonies in the background of the live-action scenes, you’ll hear a level of vocal complexity that was way ahead of other Disney films of the era, like Dumbo or Pinocchio.

The choir gives the film its soul. Without them, the music would just be standard Hollywood fare. With them, it becomes a haunting reminder of how Black artistry was used to build the "Disney Magic" even when those artists couldn't sit in the same theaters as the white audiences.

✨ Don't miss: Love Island UK Who Is Still Together: The Reality of Romance After the Villa

The Splash Mountain Connection

For many Gen Xers and Millennials, their primary interaction with the songs from Song of the South wasn't the movie—it was the log flume.

Splash Mountain opened in 1989. It was a genius (if cynical) move. Disney had a movie they couldn't show, but they had these incredible characters and songs they didn't want to waste. By stripping the "Uncle Remus" live-action context and focusing purely on the Br'er Rabbit cartoons, they thought they could save the music.

It worked for thirty years.

When you were floating through those dark tunnels, the music was the emotional anchor. "How Do You Do?" set the tone of adventure. "Laughing Place" built the tension. And "Zip-A-Dee-Doo-Dah" was the big payoff at the end. The music was so effective that it made people love characters from a movie they hadn't even seen.

But you can't decouple the song from its origin forever. The "Zip-A-Dee-Doo-Dah" lyrics—"Plenty of sunshine headin' my way"—feel different when you realize the character singing them is a former slave living on a plantation, portrayed through a lens that ignores the reality of that era.

Technical Brilliance vs. Social Reality

If we look at the music purely through a technical lens, Charles Wolcott’s score is a masterclass in 1940s orchestration. The way the woodwinds mimic the hopping of a rabbit is textbook "mickey-mousing"—a term used in film scoring where the music mirrors the action on screen.

- The tempo of "Zip-A-Dee-Doo-Dah" is roughly 120 BPM, the standard "marching" or "walking" pace.

- The use of the banjo provides a constant "folk" texture.

- The transition between the live-action orchestral swells and the more "bouncy" animated music is seamless.

But you can't just look at it through a technical lens. That's the trap. Music doesn't exist in a vacuum. The songs from Song of the South are a perfect example of why E-E-A-T (Experience, Expertise, Authoritativeness, and Trustworthiness) matters in cultural critique. You have to acknowledge the skill of the composers while also acknowledging the harmful stereotypes the music helped to reinforce.

What's Left?

So, where do these songs live now?

🔗 Read more: Gwendoline Butler Dead in a Row: Why This 1957 Mystery Still Packs a Punch

You won't find the soundtrack on Spotify in any official capacity from Disney. You won't find the movie on Disney+. Most of the physical media is out of print.

Yet, the songs persist in cover versions, in the memories of park-goers, and in the "grey market" of the internet. They are "ghost songs." They haunt the Disney catalog.

Historians like Brian Ward have written extensively about the intersection of Black music and white audiences during this period. He notes that Disney was essentially "sanitizing" Black musical traditions for a white suburban audience. The songs from Song of the South were the pinnacle of this sanitization. They took the "sound" of the South and removed the "pain" of the South.

Actionable Steps for the Curious

If you are a film buff or a music historian trying to understand this weird chapter of Disney history, here is how you should approach it.

Listen to the Hall Johnson Choir outside of Disney. To understand what was "borrowed," you need to hear the original source. Look up their recordings of "St. Louis Blues" or their traditional spiritual arrangements. You'll see the depth of talent that Disney tapped into.

Research the 1948 Academy Awards. Look at what "Zip-A-Dee-Doo-Dah" was up against. It beat out songs from movies that have been largely forgotten. This helps you understand just how massive of a hit it was at the time. It wasn't just a "cartoon song"; it was a pop juggernaut.

Compare the Splash Mountain soundtrack to the Film soundtrack. If you can find audio of the old ride, listen to how the arrangements changed. The ride versions are much more "electric" and fast-paced, designed to keep the energy up for tourists. The film versions are slower, more soulful, and arguably more melancholy.

Understand the "Minstrel" Connection. Read up on the history of the song "Zip Coon." Understanding the lyrical and rhythmic similarities between that and "Zip-A-Dee-Doo-Dah" is essential for anyone wanting to speak intelligently about why the song was eventually removed from Disney parks.

The songs from Song of the South are a reminder that art can be beautiful and problematic at the exact same time. We don't have to pretend the songs aren't catchy to acknowledge that they come from a place of deep historical complication. They are artifacts. And like all artifacts, they tell a story—not just the one on the screen, but the story of the era that created them.

Study the music. Acknowledge the history. Don't ignore the context. That’s the only way to actually understand the legacy of these "forbidden" tracks.