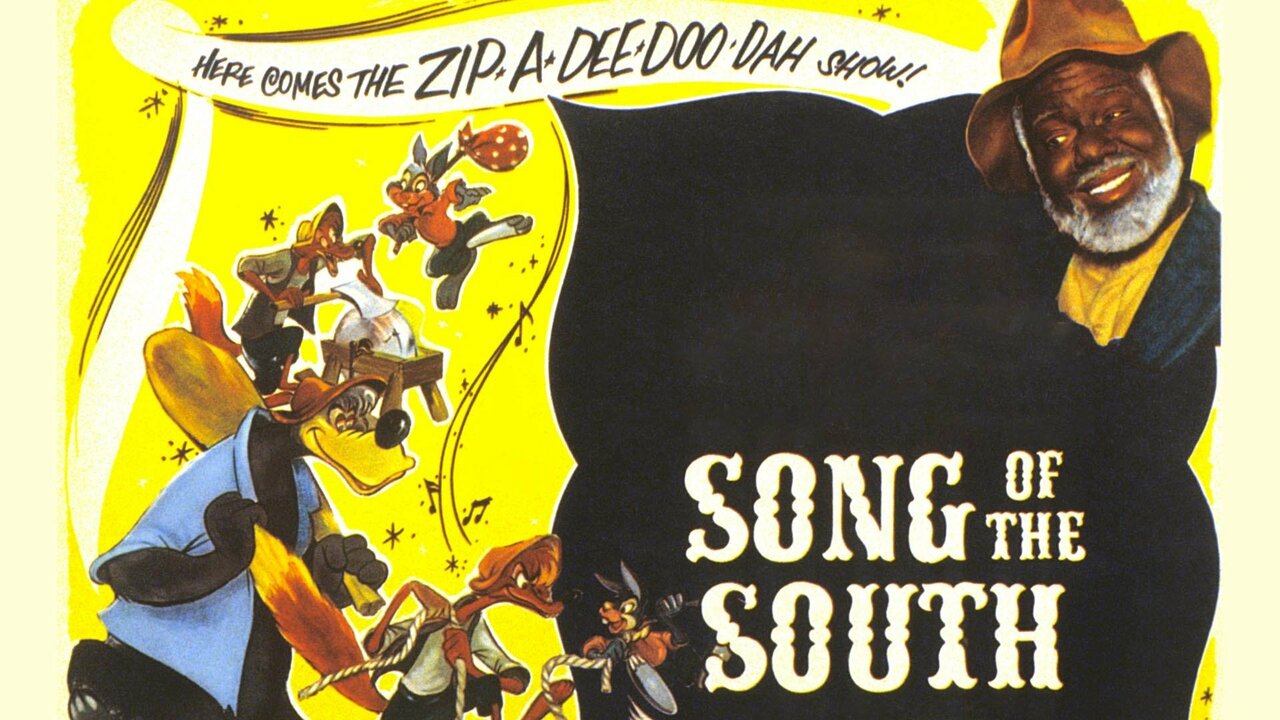

Most people under the age of thirty have never actually seen the movie. They know the ride—or they knew it, before it was re-themed—and they definitely know the "Zip-a-Dee-Doo-Dah" melody. But the film itself, the 1946 live-action and animated hybrid Song of the South, has effectively been scrubbed from existence by the very company that created it. It’s a ghost in the machine. Disney has locked it in a metaphorical vault so tight that even Disney+ subscribers can’t find a trace of it. Honestly, it’s one of the most fascinating instances of corporate self-censorship in Hollywood history.

You’ve probably heard it’s "racist." That’s the shorthand. But the reality of why Song of the South remains so toxic to the Disney brand is actually more complicated than a single label. It’s about the intersection of Reconstruction-era politics, the specific tropes of the "Old South," and a legendary animator’s desire to push the boundaries of technology while remaining stubbornly blind to the cultural implications of his work. Walt Disney wasn't trying to make a hateful film. He thought he was making a heartwarming one. That’s exactly where the trouble started.

The Myth of the Happy Plantation

The movie is based on the Uncle Remus stories by Joel Chandler Harris. Harris was a journalist in Atlanta who had spent his childhood listening to the folk tales of enslaved people. He wrote them down in a heavy, phonetic dialect that even back in the late 1800s was controversial. When Walt Disney decided to adapt these stories, he walked right into a buzzsaw of racial tension that he simply didn't understand.

The central problem isn't necessarily the stories of Br'er Rabbit, Br'er Fox, and Br'er Bear. Those are classic trickster fables with roots in African folklore. The problem is the framing. The film is set during the Reconstruction era, but it looks, smells, and feels like the antebellum South. James Baskett plays Uncle Remus, a black man who seems perfectly content living in a shack on a plantation, telling stories to white children while the "happy" black workers sing in the fields.

It’s an idyllic version of a period that was actually defined by Jim Crow laws, lynchings, and extreme poverty. By painting this period with a golden, nostalgic brush, Disney inadvertently validated the "Lost Cause" narrative. This wasn't just a 2020s realization. The NAACP was protesting the film as early as its premiere in Atlanta in 1946. They argued that it helped to perpetuate a "dangerously glorified picture of slavery." Technically, the characters aren't slaves—the movie is set after the Civil War—but the power dynamics haven't shifted an inch.

Why Splash Mountain Stayed When the Movie Left

It’s weird, right? For decades, you could go to Disneyland or Disney World and drop 50 feet into a briar patch while listening to the soundtrack of a movie the company refused to sell on DVD. Splash Mountain was a massive hit. It’s arguably one of the best-designed log flumes ever built.

The ride worked because it stripped away the live-action "Uncle Remus" segments and focused entirely on the animated animals. Most kids riding it in the 90s had no idea who Uncle Remus was. They just liked the rabbit who outsmarted the fox. Disney leaned into this. They figured they could keep the "IP" (intellectual property) alive through the characters while burying the problematic context of the film.

But the internet changed things.

✨ Don't miss: Why October London Make Me Wanna Is the Soul Revival We Actually Needed

In the age of instant information, you can't have a massive mountain in the middle of a theme park dedicated to a film that is widely considered a racial caricature. The disconnect became too loud. Eventually, Disney announced the transformation of the ride into Tiana’s Bayou Adventure, themed after The Princess and the Frog. It was a business move as much as a social one. You can't sell merchandise for a movie you're too embarrassed to show.

James Baskett and a Bittersweet Legacy

We have to talk about James Baskett. His performance as Uncle Remus is genuinely magnetic. He had this warmth and a specific kind of gravitas that made the character feel real, even when the script was doing him no favors.

Walt Disney actually campaigned for Baskett to receive an Academy Award. Because he wasn't a member of the Screen Actors Guild at the time, he couldn't be nominated for a standard Oscar, but he was given an Honorary Award in 1948. This made him the first African American man to win an Oscar.

The tragedy is that Baskett couldn't even attend the film's premiere in Atlanta because of segregation. The star of the movie wasn't allowed in the theater. That's the reality of the era Song of the South tried to pretend was a sun-drenched paradise. Baskett died just months after receiving his Oscar, leaving behind a legacy that is forever tied to a film that the world is trying to forget.

The Technical Brilliance Nobody Mentions

If you strip away the social politics for a second—which is hard, I know—the movie is a technical masterpiece. At the time, combining live-action actors with animated characters was incredibly difficult. Disney had done it before in the "Alice Comedies" and The Three Caballeros, but Song of the South took it to another level.

The lighting on the animated characters often matches the live-action environment. When Br'er Rabbit interacts with Uncle Remus, the eye lines are almost perfect. This was groundbreaking stuff in 1946. It paved the way for movies like Who Framed Roger Rabbit and Mary Poppins.

The animation itself, led by legends like Milt Kahl and Marc Davis, is some of the most fluid and expressive work the studio ever produced. Br'er Rabbit isn't just a cartoon; he has a weight and a manic energy that feels modern even today. It’s a shame that such high-level artistry is trapped inside a vessel that is so fundamentally flawed.

🔗 Read more: How to Watch The Wolf and the Lion Without Getting Lost in the Wild

The International Loophole and the Bootleg Market

Disney hasn't released Song of the South on home video in the United States, ever. Not on VHS, not on LaserDisc, certainly not on Blu-ray. Former CEO Bob Iger was very vocal about the fact that it just didn't fit the brand anymore. He called it "not appropriate in today's world."

However, the film was released in other territories. You used to be able to find PAL-format VHS tapes from the UK or Japan. For years, collectors would hunt these down, or buy "grey market" DVDs at comic book conventions. Today, you can find high-definition "restorations" on various archive sites, often scanned from old 35mm film prints by fans.

The irony is that by banning the film, Disney has made it a cult object. People want to see the "forbidden" movie. When you hide something, you give it power. If Disney had released it with a scholarly introduction—similar to how they handled the "Walt Disney Treasures" sets or how Warner Bros. handles the "Censored Eleven" Looney Tunes—the conversation might be different. Instead, it exists in a state of digital limbo.

The Actual Plot (Because Most People Forget It)

The story isn't actually about the South as a whole; it’s a very small, domestic drama. A young boy named Johnny is staying at his grandmother’s plantation while his parents are going through a trial separation (though the movie describes it vaguely). Johnny is miserable. He wants to run away.

He meets Uncle Remus, who uses the stories of Br'er Rabbit to teach Johnny how to handle his problems. When Johnny is bullied by the neighborhood kids, Remus tells him the story of the Tar-Baby. When Johnny is lonely, he hears about the Laughing Place.

It’s basically a movie about a lonely kid and his imaginary (or storytelling) friend. The stakes are incredibly low until the very end when Johnny gets chased by a bull. It’s a strange, slow-paced film that likely wouldn't hold the attention of a modern audience even if the racial elements weren't an issue.

Impact on the Disney Brand

Disney is a company built on nostalgia. They sell the past. But Song of the South represents a version of the past that the company can no longer stand behind.

💡 You might also like: Is Lincoln Lawyer Coming Back? Mickey Haller's Next Move Explained

The internal debate at Disney must have been wild. On one hand, you have "Zip-a-Dee-Doo-Dah," which was the unofficial anthem of the company for decades. On the other, you have a character who is a direct descendant of the "minstrel" tradition.

The slow erasure of the film's presence—removing the song from park loops, re-theming the rides, pulling the movie from circulation—shows a company trying to pivot its entire identity. They want to be the "most inclusive" brand on earth. You can't do that while profit-sharing with a film that uses the word "darkey" (which appears in the original Harris books, though Disney sanitized the language for the film).

What We Can Learn from the Controversy

The story of this film isn't just about "cancel culture." It’s about how art ages. Some things that were considered progressive or "charming" in 1946 are revealed to be deeply hurtful when viewed through a wider lens.

- Context is everything. You can't separate the stories of Br'er Rabbit from the environment they were told in.

- Intent doesn't equal impact. Walt Disney didn't have "hate in his heart," but he had a massive blind spot regarding the lived experiences of Black Americans.

- Erasure is rarely successful. By hiding the film, Disney created a vacuum that was filled by curiosity and bootlegs.

If you really want to understand the history of American animation, you eventually have to deal with this movie. You can't just pretend it didn't happen. It’s a piece of the puzzle, even if it’s a piece that doesn't fit the picture Disney is trying to paint today.

Practical Steps for the Curious

If you are looking to understand the controversy more deeply without scouring the dark web for a bootleg, there are better ways to engage with the history.

- Read the Joel Chandler Harris books. You can find them in most libraries. They are difficult to read because of the phonetic dialect, but they provide the raw material Disney was working with.

- Watch the documentary Disney's Erasure of Song of the South. Many film historians have created video essays that show clips of the film while explaining the historical context.

- Research James Baskett. His story is worth knowing independently of the movie. He was a pioneer who worked in "race films" long before he ever met Walt Disney.

- Compare the ride to the film. Look at old POV videos of Splash Mountain and see how the Imagineers attempted to "fix" the story by removing the human elements.

Ultimately, Song of the South serves as a permanent reminder that even the most "magical" companies are products of their time. Understanding why it’s hidden is more important than actually watching the movie itself. It tells us more about where we’ve been—and where we are going—than any fairy tale ever could.