You’re flipping through the Bible, past the laws about mildew and the long lists of who begat whom, and suddenly you hit the Song of Songs. It’s a shock. Honestly, it feels like stumbling into the wrong theater. One minute you’re reading about burnt offerings, and the next, there’s a woman describing her lover’s "radiant and ruddy" skin and a guy comparing his partner’s hair to a flock of goats. It’s spicy. It’s weird. It’s also one of the most debated pieces of literature in human history.

People get uncomfortable.

For centuries, religious scholars tried to pretend the Song of Songs was just a big metaphor for God’s love for the church or Israel. They had to. If they didn't, they’d have to admit that right in the middle of the Holy Scriptures, there’s a collection of erotic love poems that never once mentions "God," "law," or "sin." It’s just raw, human desire. And yet, that’s exactly why it’s so powerful. It grounds the divine in the dirt and sweat of real life.

What's Really Going On in the Song of Songs?

Most people assume this is a story with a beginning, middle, and end. It’s not. It’s more like a mixtape of lyric poems. You’ve got two main voices—a woman (the Shulammite) and a man (often associated with Solomon, though scholars like Robert Alter argue the "Solomon" mentions might be more of a literary trope for "the ideal kingly lover").

They’re chasing each other. They’re losing each other. They’re finding each other again in gardens and vineyards.

The language is... intense. When the man says his "beloved is to me a cluster of henna blossoms in the vineyards of En Gedi," he’s not just being poetic. En Gedi was a literal oasis in the middle of a brutal desert. He’s saying she is his life-support system. She is the green in a world of brown. That’s a level of passion that goes beyond a Hallmark card.

The Problem With Solomon

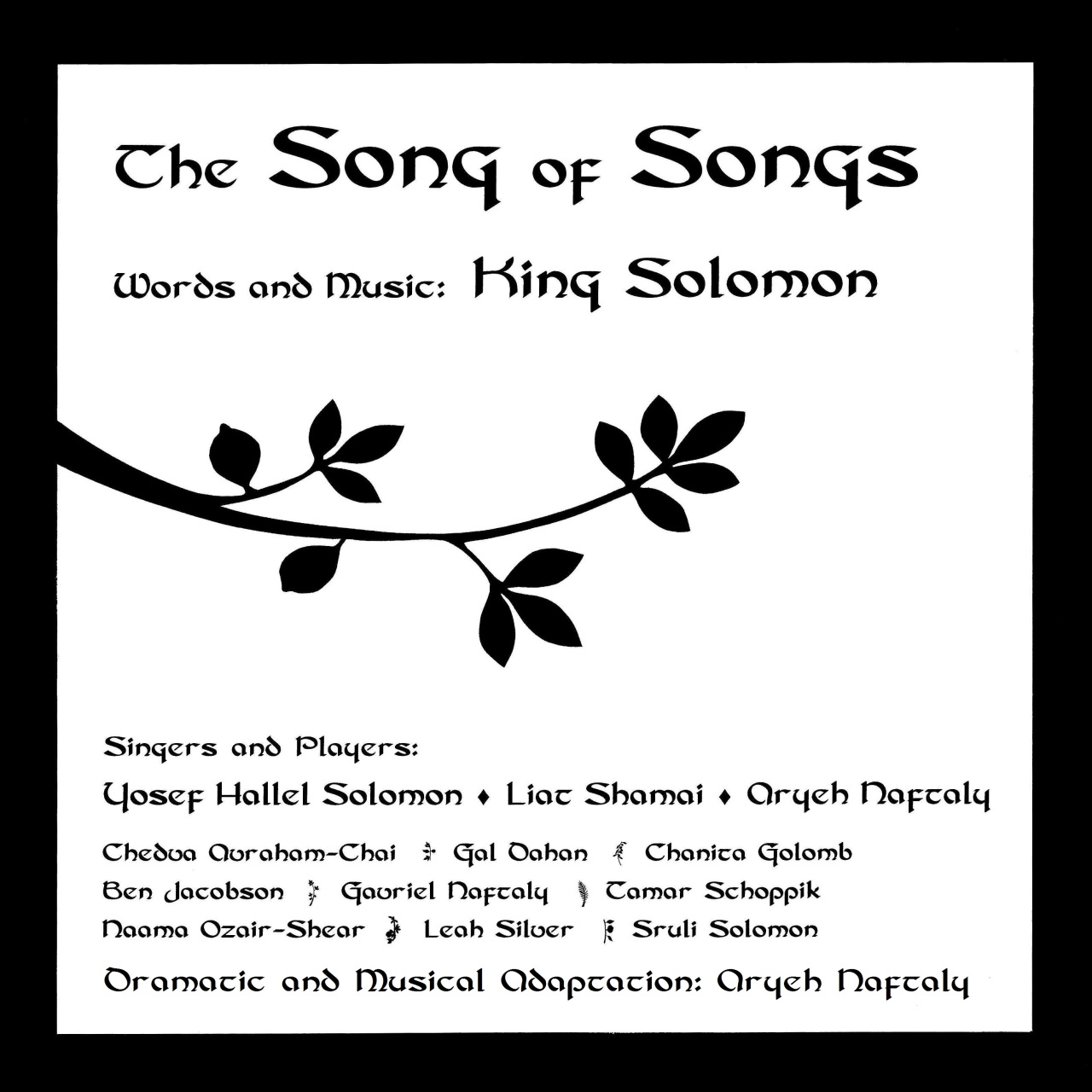

We call it "The Song of Solomon," but did he write it? Probably not. The Hebrew title, Shir HaShirim, translates to the "Song of Songs," which is a way of saying "the greatest song ever." Kinda like the "King of Kings."

📖 Related: Kiko Japanese Restaurant Plantation: Why This Local Spot Still Wins the Sushi Game

Historians look at the language—there are bits of Aramaic and even a few Greek-influenced words—and suggest it was compiled much later than the 10th century BCE when Solomon lived. Maybe the 4th or 3rd century BCE. It doesn’t matter who held the pen, though. What matters is the shift in perspective. In a world where women were often treated as property, the woman in the Song of Songs has a massive amount of agency. She initiates. She seeks. She speaks more than the man does. She’s the protagonist of her own desire.

Why Religious Groups Tried to "Clean It Up"

The Rabbis of the Mishnah had some heated arguments about this book. Rabbi Akiva famously defended it, saying, "The whole world is not worth the day on which the Song of Songs was given to Israel; for all the Scriptures are holy, but the Song of Songs is the Holy of Holies."

That’s a bold claim.

To make it work, the interpretive tradition went into overdrive. The "breasts" mentioned in the text became the "Two Tablets of the Law." The "kisses" became the "Oral and Written Torah."

It’s a bit of a stretch, isn’t it?

But here’s the thing: you don't actually have to choose between the literal and the spiritual. If you believe that a Creator made humans with the capacity for physical intimacy and emotional longing, then a book celebrating that isn't a distraction from God. It’s a reflection of God. St. Bernard of Clairvaux wrote 86 sermons on just the first two chapters of this book. He saw the soul’s longing for the Divine mirrored in the lover’s longing for her partner. It’s about the intensity of the connection.

👉 See also: Green Emerald Day Massage: Why Your Body Actually Needs This Specific Therapy

The Structure of Desire

The book is famously circular. If you’re looking for a marriage ceremony or a "happily ever after" ending, you’ll be disappointed. It ends almost exactly where it begins—with the lovers calling out to each other, still yearning.

- The Seek and Find: The woman wanders the city streets at night looking for her lover. She asks the watchmen where he is. This happens twice. It’s an ancient anxiety dream about losing the person you love most.

- The "Wasf": This is a technical term for those long, descriptive passages where they praise each other’s bodies from head to toe. It’s a traditional Near Eastern poetic form.

- The Garden Imagery: The garden is a huge deal. It’s a callback to Eden. But unlike Eden, where everything went sideways, this garden is a place of restoration.

Why Modern Readers Still Care

We live in a world that either over-sexualizes everything or tries to make it clinical and boring. The Song of Songs does neither. It treats physical love as something sacred, mysterious, and even a little bit dangerous.

"Love is as strong as death," the text says. Think about that for a second. That is a terrifyingly high stake. It’s saying that the bond between two people has the same gravitational pull as the end of life itself. It’s not a hobby. It’s not a "vibe." It’s an elemental force.

When the woman says, "Do not rouse or awaken love until it so desires," she’s giving some of the best relationship advice ever written. She’s saying that this stuff is powerful. Don't mess with it if you aren't ready for the fire. You can’t force it, and you shouldn't rush it.

Dealing with the Weird Metaphors

Let's be real: telling a woman her nose is like "the tower of Lebanon looking toward Damascus" won't get you a second date in 2026.

But context is everything. To an ancient listener, a tower was a symbol of symmetry, strength, and elegance. To say her teeth are like "a flock of sheep coming up from the washing" meant they were white, perfectly paired, and complete (no missing teeth). It’s the ultimate "you’re perfect" compliment for the time.

✨ Don't miss: The Recipe Marble Pound Cake Secrets Professional Bakers Don't Usually Share

The imagery is agrarian because that was their world. They saw beauty in the land, the harvests, and the animals. When we read it today, we have to look past the "goats" and "towers" and see the intent: absolute, unadulterated admiration.

The Scandal of Joy

There is a strange lack of "moralizing" in these pages. There are no "thou shalt nots." There is no mention of procreation. In the rest of the Bible, sex is often linked to building a lineage or fulfilling a duty. Here, it’s just for joy.

It’s about the delight of being seen and known by another person.

This is probably why the book has survived so many attempts to censor it. You can’t kill a song that resonates with the most basic human experience. We all want to be the "lily among thorns" to someone. We all want to feel that our presence is "fragrant like Lebanon."

How to Read Song of Songs Today

If you want to actually "get" this book, stop trying to find a secret code. Stop trying to turn every pomegranate into a theological point.

- Read it aloud. This was meant to be heard. The rhythm matters.

- Look for the "Daughters of Jerusalem." They act like a Greek chorus, asking questions and cheering the lovers on. They represent the community watching this love unfold.

- Acknowledge the tension. Notice how often the lovers are apart. The book is as much about the absence of the beloved as it is about their presence.

- Compare translations. Some versions (like the King James) make it sound very formal. Modern translations like the NRSV or Robert Alter’s version bring out the earthiness and the grit.

The Song of Songs reminds us that the spiritual life isn't lived in the clouds. It’s lived in the body. It’s lived in the "clefts of the rock" and the "shadow of the apple tree." It’s a wild, untamed piece of literature that refuses to be put in a box.

Whether you see it as a blueprint for human romance or a fever dream of divine longing, it demands your attention. It’s a reminder that at the center of the universe—at least according to this ancient poet—is a love that is "flashing like fire, a flame of the Lord."

Practical Steps for Further Study:

- Read the Wasfs: Look at Chapters 4, 5, and 7 specifically. Compare how the man describes the woman versus how she describes him. Note the focus on strength for him and fertility/beauty for her.

- Research Ancient Near Eastern Love Poetry: Check out Egyptian love songs from the New Kingdom period. You’ll find shocking similarities in the "brother/sister" terminology and the garden metaphors.

- Look at the Hebrew: Use an interlinear Bible to look at the word dodim. It’s often translated as "love," but it specifically refers to the physical acts of lovemaking, distinct from ahava, which is the broader concept of love. This helps clarify just how literal the text intended to be.

- Explore the Liturgy: If you're interested in the Jewish tradition, look at how the Song is read during Passover. Consider why a book about springtime and love is paired with a holiday about liberation. Hint: It’s because both are about a new beginning and a fierce, redeeming passion.