Ever looked at a brick and thought about how busy it is? Probably not. It's just sitting there. Static. Boring. But if you could shrink down—way past the cellular level, past the microscopic, right down into the nanometer range—you’d see that what we know about a solid's molecules is that they are anything but still.

Everything around you is humming. That coffee mug? It’s a mosh pit of particles. The floor under your feet? It’s a rigid grid of atoms locked in a high-speed shiver. We tend to think of solids as "finished" objects, but they are actually dynamic systems held together by some of the most powerful forces in the universe.

The Great Misconception of Stillness

Most people think "solid" means "stopped." We’re taught in grade school that solids stay put while liquids flow and gases fly away. That’s a decent starting point, but it's technically a lie.

In reality, a solid's molecules are constantly vibrating. They have kinetic energy. Even at room temperature, they are shaking back and forth within a very specific, confined space. They want to move. They want to fly off. But they can't. They are trapped by intermolecular forces—think of them as invisible, incredibly strong springs—that snap them back into place every time they try to wander.

This shaking is what we perceive as temperature. If you heat that solid up, the molecules shake harder. If you cool it down, they settle. But they never truly stop until you hit absolute zero ($0\text{ K}$ or $-273.15^\circ\text{C}$), a theoretical point where all motion ceases. Even then, quantum mechanics suggests there's still a tiny bit of "zero-point" energy left over.

Why Stuff Doesn't Just Fall Apart

What’s actually keeping the molecules in a solid from just drifting away like a cloud of steam? It’s all about the "bond."

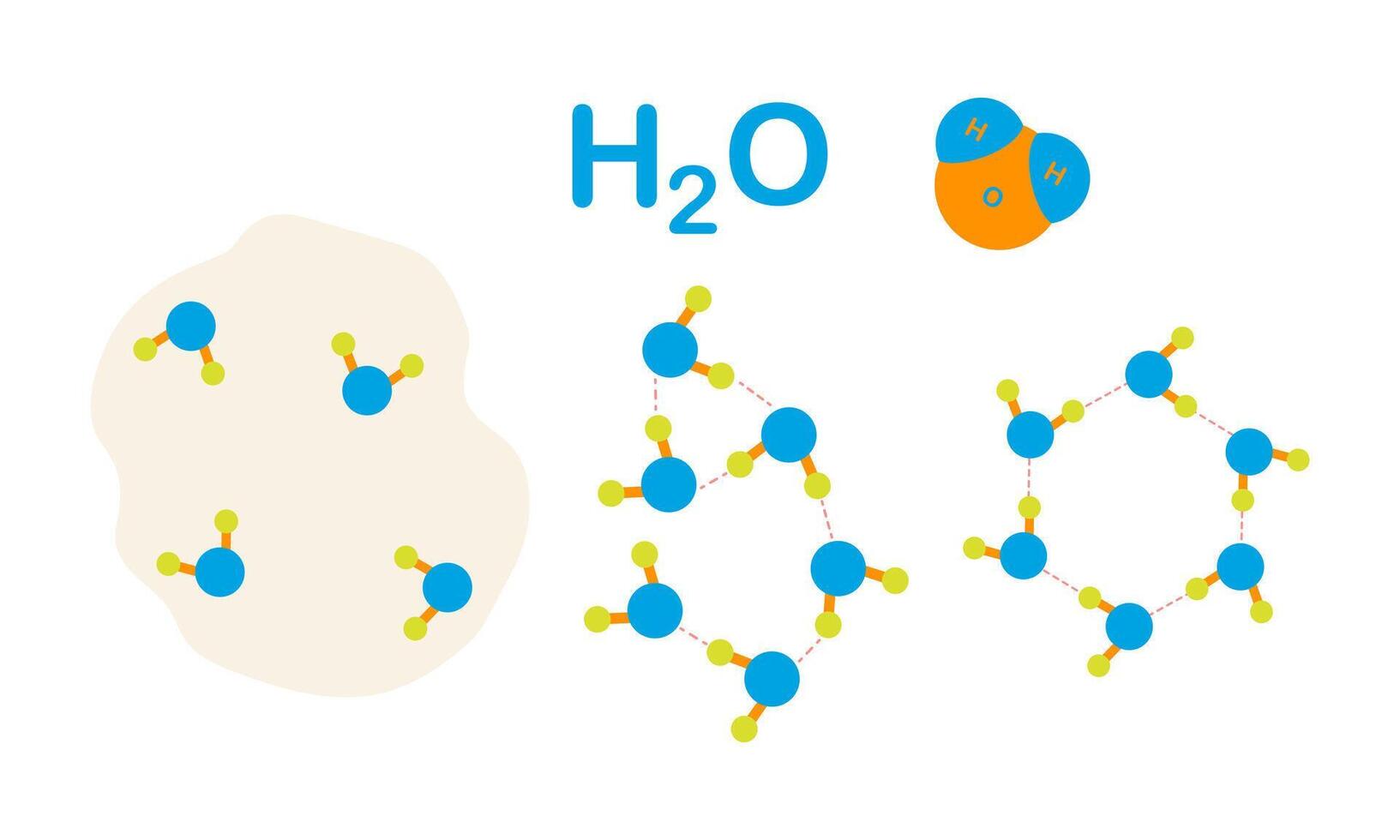

Depending on what you’re looking at, those molecules are held together by different "glues." In a diamond, you’ve got covalent bonds where atoms are literally sharing electrons in a death-grip. In a block of ice, it’s hydrogen bonding—a weaker, "electrostatic" attraction that’s still strong enough to keep things together until the sun comes out.

The arrangement is the key. In most solids, the molecules organize into a crystal lattice. It’s a repeating, geometric pattern. It’s why salt looks like tiny cubes under a magnifying glass and why snowflakes have six sides. The molecules find the "laziest" way to sit—the position that requires the least amount of energy—and they stay there.

Amorphous Solids: The Outliers

Not everything follows the rules. Some solids are basically "failed" liquids.

Take glass. Or plastic. Or wax. These are called amorphous solids. When these materials cooled down from a liquid state, the molecules didn't have enough time to find their perfect seats in the lattice. They just got stuck wherever they were. Honestly, glass is more like a photograph of a liquid frozen in time than a "true" solid. Because the molecules are disorganized, amorphous solids don’t have a sharp melting point. They just get softer and softer until they’re gooey.

A crystal, like an ice cube, is different. It stays rock hard until it reaches $0^\circ\text{C}$, and then—boom—it starts turning to water. That’s because every bond in a crystal lattice is identical, so they all break at the exact same temperature.

How Do We Actually "See" This?

We can't just use a standard microscope to see a solid's molecules. The wavelength of visible light is actually too "fat" to bounce off an individual molecule. It would be like trying to find a needle in a haystack using a wrecking ball.

Scientists like Max von Laue and the father-son duo William and Lawrence Bragg figured out we could use X-rays instead. X-rays have tiny wavelengths. When you shoot them at a solid, they bounce off the molecules and create a diffraction pattern. It’s like seeing the shadow of a bird and figuring out exactly what kind of bird it is.

Today, we use Scanning Tunneling Microscopes (STM). These don't even use light. They use a needle so sharp the tip is a single atom wide. By "feeling" the electron clouds of the molecules, we can create maps of what's happening at the atomic level. This is how we know for a fact that the molecules are arranged in those beautiful, rigid grids we see in textbooks.

Pressure, Heat, and the Breaking Point

What happens when you push a solid too far?

Everything has a limit. When you apply heat, you’re essentially injecting "chaos" into the system. The molecules vibrate faster and faster. Eventually, the vibration becomes so violent that the "springs" (the bonds) can’t hold them anymore. The molecules break free and start sliding past each other. That’s melting.

But pressure changes the game. If you squeeze a solid hard enough, you can actually force the molecules into new shapes. This is how we get synthetic diamonds. You take carbon (graphite), which has molecules arranged in flat, slippery sheets, and you crush it until those molecules have no choice but to bond into a dense, 3D pyramid structure.

Real-World Implications: Why Engineers Care

Knowing about a solid's molecules isn't just for physicists in lab coats. It’s the reason your phone doesn't melt in your pocket and why bridges don't snap in the winter.

- Thermal Expansion: Since molecules shake more when hot, they need more "elbow room." This makes the solid grow. It's why bridges have those weird metal teeth (expansion joints)—to give the molecules room to dance without buckling the pavement.

- Doping in Electronics: In the tech world, we take a solid like Silicon and intentionally replace a few of its molecules with something else, like Boron. This "doping" changes how electrons move through the lattice, which is basically how every computer chip on Earth works.

- Material Fatigue: Ever bend a paperclip back and forth until it breaks? You’re literally disrupting the molecular alignment. You’re creating tiny "dislocations" in the lattice that grow until the whole structure fails.

The Density Mystery

Usually, molecules in a solid are packed tighter than they are in a liquid. This makes sense. If they’re locked together, they should take up less space.

But water is the weirdo. When water freezes into a solid, the molecules actually spread out to form a hexagonal lattice. This makes ice less dense than liquid water, which is why ice floats. If water behaved like most other solids, ice would sink to the bottom of the ocean, the poles would be solid blocks of ice from the floor up, and life on Earth probably wouldn't exist.

Actionable Insights for the Curious

If you want to see these molecular principles in action without a multi-million dollar lab, try these "home experiments" to observe how molecular structures behave:

🔗 Read more: AirPods 4 with ANC: Why This Hybrid Design Actually Works

1. The "Hot vs. Cold" Diffusion Test

Drop a bit of food coloring into a glass of ice water and a glass of hot water. Don't stir. You'll see the color spread much faster in the hot water. Why? Because the molecules in the liquid are slamming into the dye particles with more kinetic energy. It's a direct window into molecular motion.

2. Growing Your Own Lattices

Dissolve as much salt or sugar as you can into boiling water. Let it sit undisturbed for a week with a string hanging in it. As the water evaporates, the molecules will find each other and "lock" into their preferred geometric shapes. You'll see the macro-version of that microscopic crystal lattice.

3. Observe Thermal Expansion

If you have a stuck metal jar lid, run it under hot water. The metal (a solid) expands faster than the glass (another solid) because its molecules react more vigorously to the heat. The "gap" between the molecules grows, the lid expands, and it pops right off.

Understanding a solid's molecules changes how you see the world. It turns a static, "dead" environment into a buzzing, vibrating, energetic masterpiece of physics. The chair you’re sitting on isn't just a piece of wood or plastic; it’s a trillion-trillion particles performing a perfectly choreographed, high-speed balancing act. Once you realize that, "solid" starts to feel like a very relative term.