You’re standing in a field, or maybe a parking lot, squinting through a pair of cardboard glasses that cost two dollars and look like 1950s 3D movie gear. The air gets weirdly cold. Not just "the sun went behind a cloud" cold, but a sudden, metallic chill that raises the hair on your arms. Birds stop singing. Crickets start chirping because they think it's night. Then, the sun vanishes. In its place is a black hole in the sky surrounded by a ghostly, shimmering halo. This is what happens with a solar eclipse, and honestly, no photograph ever really captures the primal "oh no" feeling your brain produces when the physics of the sky suddenly breaks.

Most people think it’s just a shadow. Technically, sure. But it’s a celestial alignment so precise it feels like a glitch in the matrix.

🔗 Read more: iPhone 16 Pro Screen Protector: Why Most People Are Still Buying the Wrong One

The Mechanics of the Perfect Shadow

A solar eclipse is a game of cosmic scale and perspective. The Sun is about 400 times larger than the Moon. By a freak coincidence of evolution and planetary physics, the Sun is also about 400 times farther away from Earth than the Moon is. This means that from our specific vantage point on this specific rock, they appear to be the almost exact same size in the sky. If the Moon were smaller or further away, we’d never have a total eclipse. We’d just have a transit, like when Venus passes in front of the sun and looks like a tiny mole.

The moon’s orbit isn’t a perfect circle. It’s an ellipse. Because of this, the moon isn't always the same distance from us. When it's at its furthest point (apogee) and crosses the sun, it can’t cover the whole thing. You get a "Ring of Fire," or an annular eclipse. But when it’s closer, you get the big one. Total darkness.

Shadow Geometry

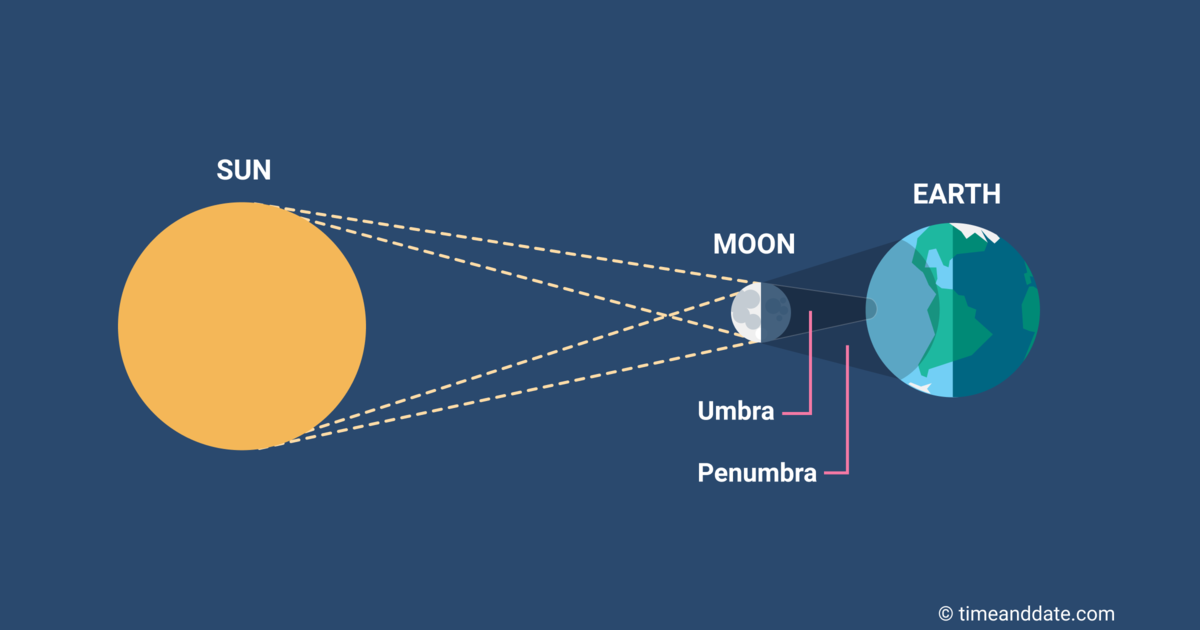

There are two main parts to the shadow the moon throws at us. The penumbra is the outer, lighter shadow. If you’re standing in the penumbra, you see a partial eclipse. The sun looks like a cookie with a bite taken out of it. It's cool, but it’s not life-changing.

Then there’s the umbra.

This is the dark, slender cone of the moon’s shadow. To see a total solar eclipse, you have to be standing inside the "path of totality," which is usually only about 100 miles wide. Outside that path? You’re just looking at a dim afternoon. Inside? You’re in the shadow of a moon moving at over 1,500 miles per hour across the Earth's surface.

What Happens With a Solar Eclipse to Your Body and Environment?

When the moon begins its transit, things stay normal for a while. You need your ISO 12312-2 certified glasses. Don't mess around with that; your retinas don't have pain receptors, so you won't even know you're burning holes in your vision until the next day. But as the sun becomes a thin sliver, the light quality changes. It gets "sharp." Shadows on the ground become incredibly crisp because the light source is no longer a big disk but a tiny line.

If you look under a leafy tree, you'll see something wild. The tiny gaps between the leaves act like pinhole cameras. The ground will be covered in thousands of tiny crescent-shaped shadows. It looks like a psychedelic carpet.

The Temperature Drop

NASA has documented temperature drops of up to 10 or 15 degrees Fahrenheit during totality. It happens fast. This sudden cooling can actually cause "eclipse winds." As the air in the shadow cools and contracts, it creates a localized pressure change, leading to a breeze that wasn't there ten minutes ago.

Animal Confusion

Animals are honest. They don't have calendars. When the sky goes dark and the stars come out at 2:00 PM, they react. Bees have been observed stopping their flight and dropping toward the ground. Spiders may start tearing down their webs. In a famous study during the 2017 Great American Eclipse, researchers at the Riverbanks Zoo in South Carolina saw giraffes start galloping in circles and tortoises began mating. Nature gets confused when the "day" light switch is flipped off mid-afternoon.

Totality: The Moment the Rules Change

Seconds before the sun is completely covered, you see two things: Baily's Beads and the Diamond Ring. Baily's Beads are tiny flashes of light appearing around the edge of the moon. This is the sun peaking through the valleys and craters on the lunar surface. It's a reminder that the moon isn't a smooth marble; it's a jagged, ancient rock.

Then comes the Diamond Ring—one final, brilliant flash of light.

And then... gone.

The Corona Emerges

When totality hits, you can finally take the glasses off. Only during totality. You're looking at the solar corona, the sun's outer atmosphere. It’s a crown of white, wispy plasma that stretches millions of miles into space. It's actually hotter than the surface of the sun itself, a mystery that solar physicists like those working on the Parker Solar Probe are still trying to fully solve.

The sky isn't pitch black like midnight. It's a deep indigo, like a 360-degree sunset. You can see planets. Venus and Jupiter usually pop out. You might even see stars like Sirius or Regulus.

Why Scientists Obsess Over These Minutes

Total eclipses aren't just for tourism. They are the only time we can see the lowest layers of the sun’s corona without expensive space telescopes or "coronagraphs" that block the sun artificially.

Historically, what happens with a solar eclipse helped prove Einstein was right. In 1919, Sir Arthur Eddington traveled to the island of Príncipe. He photographed stars near the sun during an eclipse. Because the sun’s mass warped spacetime, the stars appeared in the "wrong" position. Gravity bent light. This observation turned Einstein into a global celebrity overnight.

Today, researchers use eclipses to study the "ionosphere." This is the layer of Earth's atmosphere filled with particles that are ionized by solar radiation. When the eclipse shadow sweeps through, it creates a "hole" in the ionosphere. This affects GPS signals and long-range radio waves. Amateur radio operators often participate in "Eclipse QSO Parties" to see how far their signals can bounce when the sun's interference is briefly removed.

Misconceptions and Eclipse Myths

People used to think eclipses were bad omens. The word "eclipse" comes from the Greek ekleipsis, meaning "abandonment."

- Myth 1: Eclipses produce "deadly" rays. No. The sun is just as "dangerous" as it is on any other day. The only difference is that during an eclipse, the dim light makes your pupils dilate, allowing more light in than usual if you're dumb enough to stare at it.

- Myth 2: You can use sunglasses. Multiple pairs of Ray-Bans won't save you. You need specialized silver polymer or black polymer filters.

- Myth 3: The shadow is always the same. Because the Earth is curved and the moon's orbit is tilted, the shadow can take weird shapes and travel at varying speeds.

How to Prepare for the Next One

Eclipses aren't actually rare; they happen somewhere on Earth about every 18 months. What's rare is one happening where you live. Most of the Earth is water, so most eclipses happen over the ocean.

If you're planning to catch one, you need more than just glasses. You need a clear horizon. You need to check cloud cover forecasts—though even if it's cloudy, the world will still turn eerie and dark, which is a vibe in its own right.

Essential Checklist

- Solar Filters: For your eyes and your camera. Do not point a DSLR at the sun without a filter; you will melt the sensor.

- A Colander: Seriously. Hold it up and look at the shadows on the ground. It’s a DIY multi-pinhole projector.

- The Path of Totality: Use sites like NASA's Eclipse Page or TimeandDate to find the exact centerline. 99% coverage is not 100% coverage. The difference between 99% and 100% is the difference between seeing a cool sunset and seeing the universe naked.

Moving Toward the Shadow

Don't just watch the sun. Watch the people around you. There's a collective gasp that happens at the moment of totality. Total strangers will start hugging or crying. It’s a reminder that we’re all riding on a spinning ball through a very busy neighborhood.

👉 See also: Order of the Solar System Planets: What Most People Get Wrong About Our Neighborhood

To make the most of the next event, start by identifying the next "path of totality" near you. Secure your lodging at least a year in advance. Small towns in the path often see their populations quadruple overnight, leading to massive traffic jams and "eclipse-pocalypse" gas shortages.

Plan your exit. The drive to an eclipse is easy; the drive back is usually a ten-hour crawl through the worst traffic of your life. But honestly? It’s worth it. Seeing the sun’s atmosphere with your own eyes is the only time you’ll ever truly feel the scale of the solar system.