When you think of the tundra, you probably imagine a vast, frozen wasteland. Endless white. Bone-chilling wind. Honestly, it’s easy to assume the ground is just a solid block of ice, but that’s not really how it works. Underneath that thin layer of moss and lichen lies a complex, messy, and frankly fascinating world of soil types in tundra that scientists are still trying to fully map out. It isn't just "frozen dirt." It’s a living carbon vault.

Most people use the word "permafrost" as a catch-all for the ground up there. That's a mistake. Permafrost is a condition, not a soil type. It refers to ground that stays at or below $0°C$ ($32°F$) for at least two years. The actual dirt on top of and within that frozen layer? That's where things get weird. You’ve got Gelisols, Cryosols, and Histosols all fighting for space in a landscape that’s basically a giant, soggy sponge for three months of the year.

The Messy Reality of Gelisols

In the official USDA soil taxonomy, the primary soil types in tundra are classified as Gelisols. If you want to get technical—and we should, because the nuance matters—Gelisols are defined by having permafrost within two meters of the surface.

But here is the thing: they aren't uniform. You can walk ten feet in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge and the soil profile changes completely because of how the water moves. Or doesn't move. Because the permafrost acts like a concrete floor, the snowmelt in the spring has nowhere to go. It just sits there. This creates a "soupy" top layer called the active layer.

This active layer is where all the action happens. It thaws in the summer, allowing roots to take hold, and then slams shut in the winter. This constant back-and-forth creates a process called cryoturbation, or frost churning. Imagine the earth literally kneading itself like dough. It pushes rocks to the surface and pulls organic matter down deep. This is why you see those strange "patterned ground" formations—perfect stone circles or polygons—that look like they were laid by aliens. It’s just the soil moving.

Histels: The Tundra’s Peat Bog

Within the Gelisol family, you have Histels. These are basically organic-rich soils that are saturated with water for long periods. Think of them as frozen peat. Because it’s so cold, dead plants don't rot properly. Fungi and bacteria are basically on a permanent coffee break because they can't handle the sub-zero temperatures. So, the moss and sedges just pile up, year after year, century after century.

👉 See also: Finding the Persian Gulf on a Map: Why This Blue Crescent Matters More Than You Think

Dr. Schuur from Northern Arizona University has done some incredible work on this. His research highlights that these soils hold about twice as much carbon as is currently in our entire atmosphere. It's a massive, frozen locker of old grass and ancient roots. If that locker thaws, we aren't just looking at mud; we are looking at a massive release of methane.

Cryosols and the High Arctic

If you head further north into the polar deserts—places like Ellesmere Island or parts of Svalbard—the soil types in tundra change again. Here, you find Cryosols. This is the term more commonly used in the World Reference Base for Soil Resources (WRB).

In these high-latitude spots, there isn't enough vegetation to make thick peat. The soil is mineral-heavy, gritty, and often alkaline. It’s raw. You’ll see a lot of Turbic Cryosols, which are the ones heavily affected by that frost-churning I mentioned earlier. You might also find Lithic Cryosols, where the bedrock is so close to the surface that the "soil" is really just a dusting of crushed stone and lichen over solid granite.

It's harsh. Extremely harsh.

Water is actually scarce here because it's locked in ice. It’s a paradox: the ground is frozen, yet the plants are often suffering from drought because they can't drink ice. This leads to a weird stunted growth where a willow tree might be a hundred years old but only two inches tall.

✨ Don't miss: El Cristo de la Habana: Why This Giant Statue is More Than Just a Cuban Landmark

The Active Layer: A Seasonal Battleground

You can't talk about soil types in tundra without focusing on the active layer. This is the 10 to 200 centimeters of soil that actually breathes.

- In late June, the sun stays up 24/7.

- The top few inches of Gelisol turn into a slurry.

- Microbes wake up and start eating.

- Plants race to flower before August.

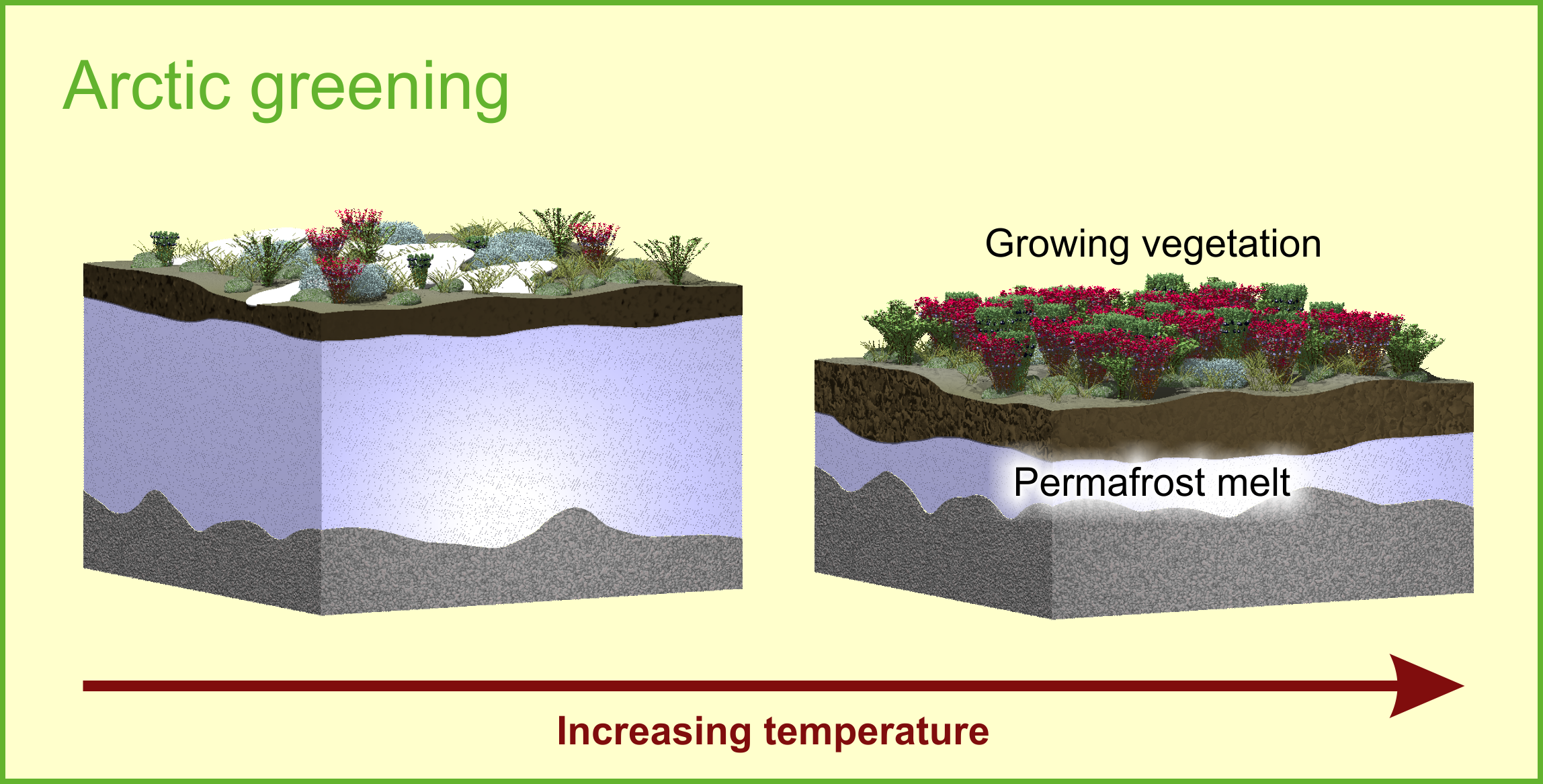

The depth of this layer is changing. Fast. In parts of the Siberian tundra, the active layer is getting deeper every year. When the active layer reaches down into old, carbon-rich Histels that have been frozen since the Pleistocene, the soil structure collapses. This is called thermokarst. The ground literally melts, creating massive sinkholes and "drunken forests" where trees tip over because the soil turned to liquid.

Soil Drainage and the "Gley" Effect

If you ever dig a hole in the tundra (which is exhausting work, trust me), you’ll notice the soil isn't usually brown. It’s often a ghostly blue-gray or greenish color. This is called gleying.

Because the soil is waterlogged and lacks oxygen (anaerobic conditions), the iron in the soil chemically reduces. It’s the opposite of rusting. Instead of bright orange ferric iron, you get dull, bluish ferrous iron. It smells like rotten eggs sometimes because of the sulfur. It’s not "pretty" soil. It’s functional, soggy, and chemically distinct.

Why Nutrients Are Hard to Find

Nitrogen is the gold currency of the tundra. In most soil types in tundra, nitrogen is locked away in organic matter that won't decompose.

🔗 Read more: Doylestown things to do that aren't just the Mercer Museum

Plants have had to get creative. Some, like the bog myrtle, have developed symbiotic relationships with bacteria to grab nitrogen from the air. Others just grow incredibly slowly. This nutrient scarcity is why the tundra is so fragile. If you drive a truck over a patch of moss, you crush the delicate soil structure and destroy the nutrient cycle. Those tire tracks can stay visible for fifty years because the soil simply doesn't have the metabolic "energy" to heal itself.

Practical Insights for the Future

Understanding these soils isn't just for academics in parkas. It matters for global climate modeling and even for engineering. If you are building anything in these regions—from a pipeline to a shed—you have to understand the latent heat of fusion in the soil.

- Monitor Thaw Depths: If you live in or visit permafrost regions, watch for new cracks in the ground or sudden ponding. This indicates the active layer is shifting.

- Support Soil Research: Groups like the International Permafrost Association (IPA) provide the data that helps us predict how much carbon might leak out of these Gelisols.

- Recognize the Sensitivity: Avoid disturbing the vegetation mat. In the tundra, the plants act as insulation. Removing the moss is like taking the lid off a cooler; the soil underneath will melt, and the land will subside.

The soil types in tundra are a reminder that the earth is a living system. Even in the coldest, most "dead" looking places, there is a complex chemistry at play. It’s a balance of ice, mineral, and ancient carbon that keeps our planet’s climate in check.

Essential Data for Reference:

- Primary Soil Order: Gelisols (USDA), Cryosols (WRB).

- Carbon Content: Roughly 1,400 to 1,600 gigatons of carbon stored in northern permafrost soils.

- Common pH Range: 3.5 to 5.5 (Acidic) in wet tundra; up to 7.5 or 8.0 in dry, polar deserts.

- Key Process: Cryoturbation (frost-churning).

Investigating the ground beneath your feet in the Arctic reveals a story of survival. These soils have been frozen for millennia, and their stability is arguably one of the most important factors in our modern environmental era.