You probably know it as baking soda. That orange box sitting in the back of your fridge, absorbing smells of last week's takeout, or the powder you throw into cookie dough to make it rise. But if you're in a lab, or maybe a high school chemistry class trying not to fail your midterm, you know it by a different name: sodium bicarbonate. And specifically, you're looking for the sodium bicarbonate molecular weight.

It's roughly 84.007 g/mol.

Wait. Don't just run off with that number yet. If you're doing precision titration or calculating how much CO2 will be released in a massive industrial reactor, those decimals actually carry some weight. Chemistry isn't just about mixing liquids and hoping for a color change; it’s a math game where the stakes involve pressure, yield, and sometimes, things blowing up when they shouldn't.

Let’s Break Down the Math (The Non-Boring Way)

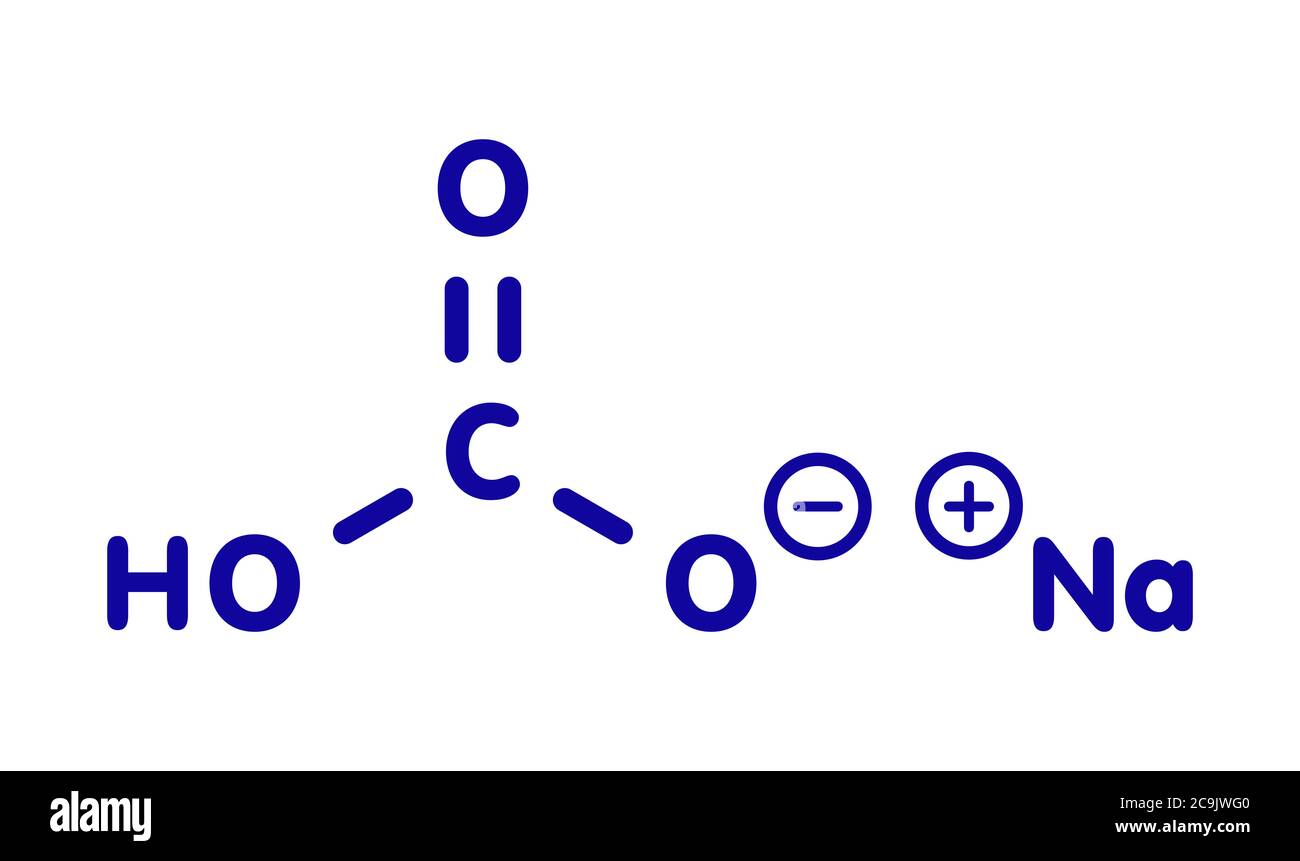

To understand where that 84.007 comes from, you have to look at the ingredients. Sodium bicarbonate has a chemical formula of $NaHCO_3$. It's a bit like a recipe. You’ve got one atom of Sodium ($Na$), one of Hydrogen ($H$), one of Carbon ($C$), and three of Oxygen ($O$).

If we look at the periodic table—and I mean the modern IUPAC versions, not the dusty one on your classroom wall from 1994—the atomic weights are pretty specific.

- Sodium (Na): ~22.990

- Hydrogen (H): ~1.008

- Carbon (C): ~12.011

- Oxygen (O): ~15.999 (but we have three of them, so that’s 47.997)

Add them up. You get 84.0066. Most people just round it to 84.01 g/mol.

Does it matter if you use 84 or 84.007? Honestly, if you’re making pancakes, no. If you’re a pharmacist compounding a metabolic acidosis treatment for a patient in the ICU, yeah, it matters a lot. Using the wrong molar mass in calculations can throw off the molarity of a solution, which, in a medical context, is the difference between helping someone and causing a dangerous electrolyte imbalance.

Why the Molecular Weight of Sodium Bicarbonate is a Big Deal in Industry

Think about fire extinguishers. Not the red ones with the foam, but the dry chemical ones. Many of them use sodium bicarbonate. When that powder hits heat, it undergoes a decomposition reaction. It breaks down into sodium carbonate, water, and carbon dioxide.

The carbon dioxide is what smothers the fire. Engineers have to calculate exactly how much powder needs to be in the canister to produce enough volume of gas to kill a flame of a certain size. They use the sodium bicarbonate molecular weight to convert the mass of the powder into moles, and then use the Ideal Gas Law to figure out the gas volume.

If their math is off because they used a sloppy molecular weight, the extinguisher might run out of "breath" before the fire is out. That's a bad day at the office.

The Kitchen Science Angle

Baking is just chemistry you can eat. When you mix baking soda with an acid—like buttermilk or lemon juice—you get a reaction. The $NaHCO_3$ reacts to release $CO_2$ gas. These tiny bubbles get trapped in the gluten of your bread or the fats in your cookies, causing them to puff up.

If you’ve ever had a cake that tasted like soap and looked like a brick, your ratios were wrong. You likely had too much unreacted sodium bicarbonate left over. Because the molar mass is relatively high compared to something like pure lithium, you need a decent amount of it to get a good rise, but not so much that the pH of your dough goes through the roof.

Stoichiometry and the "Ah-Ha" Moment

I remember helping a student once who couldn't figure out why their "volcano" experiment was pathetic. They were using a tablespoon of soda and a cup of vinegar.

Stoichiometry—which is just a fancy word for "chemistry math"—tells us that reactions happen in specific ratios. By using the sodium bicarbonate molecular weight, we can see that one mole of baking soda reacts with one mole of acetic acid (vinegar).

But a mole of baking soda weighs 84 grams, while a mole of pure acetic acid weighs about 60 grams. Since vinegar is mostly water (usually only 5% acid), you actually need a massive amount of vinegar to fully react with a small amount of soda. Most people leave a pile of unreacted white powder at the bottom of their plastic volcano because they didn't do the molar mass conversion.

Beyond the Basics: Isotopes and Precision

If you really want to nerd out, the molecular weight isn't actually a "fixed" thing in the universe. It’s an average.

Carbon, for example, isn't always Carbon-12. There’s a tiny bit of Carbon-13 hanging around in nature. Same for Oxygen. When scientists calculate the sodium bicarbonate molecular weight for high-end analytical chemistry, they have to account for the isotopic distribution.

For 99.9% of us, 84.01 is the golden number. But in fields like mass spectrometry, those tiny deviations in mass are exactly what allow researchers to identify substances in a sample. They aren't looking for "about 84"; they are looking for the exact mass of the specific molecules hitting the sensor.

Real World Application: Kidney Function

This isn't just for labs. Our bodies are walking chemical reactors. Your kidneys actually regulate the concentration of bicarbonate in your blood to keep your pH at a steady 7.4. If your blood gets too acidic, your kidneys reabsorb more bicarbonate.

Doctors measuring "total $CO_2$" in a blood panel are basically looking at the bicarbonate levels. When they need to administer a bicarb drip, they are calculating dosages based on milliequivalents ($mEq$), which is directly tied back to the molecular weight.

Wait, what's a milliequivalent?

It’s basically a way to measure the "power" of the molecules in a solution. For sodium bicarbonate, one $mEq$ is equal to one millimole ($mmol$) because the valence is 1. Since the molecular weight is 84, one $mmol$ weighs 84 milligrams.

If a doctor orders 50 $mEq$ of bicarb, they are essentially asking for 4.2 grams of the stuff ($50 \times 84 = 4200$ mg). See? Math saves lives.

✨ Don't miss: Astronauts Back From Space: The Weird Reality of Coming Home to Earth

Common Misconceptions

People often confuse sodium bicarbonate ($NaHCO_3$) with sodium carbonate ($Na_2CO_3$).

Don't do that.

Sodium carbonate, or washing soda, has a molecular weight of about 105.99 g/mol. It’s much more basic and can be caustic. If you're following a recipe or a lab protocol that calls for bicarb and you swap in carbonate because "it's basically the same," you’re going to have a very bad time. The pH shift will be way too aggressive, and in baking, it'll taste like literal cleaning supplies.

How to Calculate it Yourself (Quick Reference)

If you ever lose your phone and need to find the sodium bicarbonate molecular weight while trapped in a lab (hey, it could happen), just remember the breakdown:

- Find the atomic weights: Na (23), H (1), C (12), O (16).

- Multiply by the atoms in the formula: $Na_1 H_1 C_1 O_3$.

- Sum it up: $23 + 1 + 12 + (16 \times 3) = 84$.

Easy.

Actionable Takeaways for Your Next Project

Whether you are cleaning a tarnished silver spoon, balancing a pool, or prepping for a chemistry exam, keep these points in mind:

- For General Use: Use 84 g/mol for quick mental math.

- For Lab Work: Use 84.007 g/mol to ensure your molarity is spot on.

- Storage Matters: Sodium bicarbonate absorbs moisture from the air (it's hygroscopic). If your powder is clumpy, it has absorbed water weight, meaning your "84 grams" isn't all bicarbonate anymore. It's partly water, which will throw off your reactions. Keep it sealed!

- Check the Reactivity: Remember that the bicarbonate ion is amphoteric. It can act as an acid or a base. This versatility is why its molecular weight is cited in so many different types of chemical literature—it's one of the most useful buffers in existence.

If you're calculating a yield for a school project, always start by converting your grams to moles using that 84.007 figure. It’s the "bridge" that lets you talk to the other chemicals in the equation. Without it, you're just guessing.