Building your own vessel is a romantic, slightly insane ambition that has lived in the back of people's minds since the first person watched a log float down a river. But let’s be real for a second. If you’re looking into how to make a boat, you aren't just looking for a weekend craft project. You’re looking for a way to defy the massive price tags at the local marina and, honestly, to feel that specific kind of pride that only comes from not drowning in something you built with your own two hands.

Most people fail. They start with grand visions of mahogany-trimmed sloops and end up with a pile of rotting plywood in the garage because they didn't respect the physics of displacement or the absolute nightmare that is marine-grade epoxy.

The Myth of the Cheap "Quick" Boat

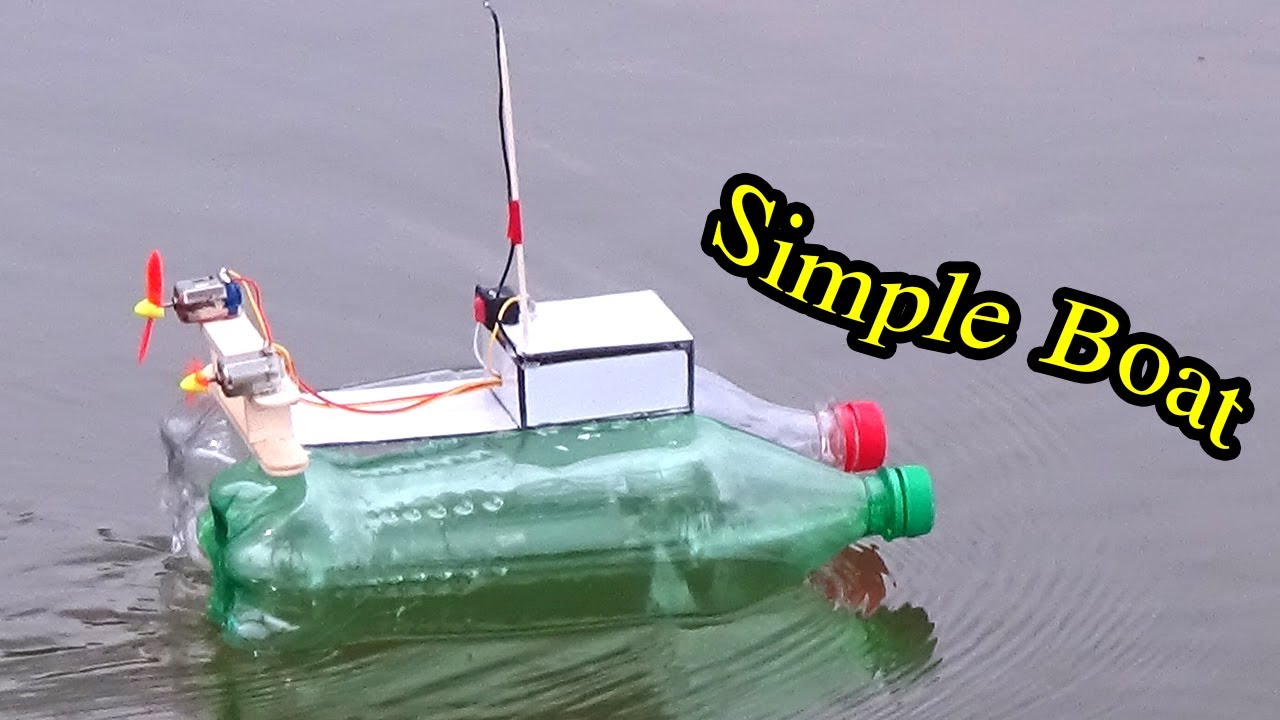

You've probably seen those videos. A guy takes three sheets of cheap exterior plywood, some construction adhesive, and a few rolls of duct tape. Presto. He's paddling across a pond. That is technically a boat, but it isn't a vessel. If you actually want to learn how to make a boat that lasts longer than a single summer afternoon, you have to ignore the "hack" culture.

Real boatbuilding is about moisture management. Water is a universal solvent; it wants to get inside your materials and turn them into mush. This is why the choice of wood matters more than almost anything else. You might think pressure-treated lumber from a big-box store is the way to go because it’s "weather-resistant." Wrong. That stuff is usually wet, heavy, and full of chemicals that make it nearly impossible for high-quality glues or fiberglass resin to actually bond. You’re better off using marine-grade okoume or even a high-quality ACX exterior plywood if you're on a budget, provided you seal every single square inch in epoxy.

Stitch and Glue: The Real Secret for Beginners

If you aren't a master shipwright with a shop full of steam-bending equipment, the "Stitch and Glue" method is basically your only sane option. It’s a technique popularized by designers like Sam Devlin and the folks over at Chesapeake Light Craft.

💡 You might also like: Dutch Bros Menu Food: What Most People Get Wrong About the Snacks

Here is how it works: you cut out flat panels of plywood based on a specific template. You drill tiny holes along the edges. You "stitch" them together using copper wire or even heavy-duty plastic zip ties. At this point, it looks like a loose, floppy wooden skeleton. But once you apply thickened epoxy (the "glue") to the seams and lay down fiberglass tape, the structure becomes incredibly rigid. It’s essentially a monocoque structure—like a modern race car—where the skin is the frame.

Why Displacement Is Not Just a Fancy Word

Physics doesn't care about your aesthetic. One of the biggest mistakes DIYers make when figuring out how to make a boat is ignoring the displacement-to-weight ratio. Archimedes' principle tells us that a floating object displaces a weight of fluid equal to its own weight.

If you build a heavy, over-engineered boat out of thick oak because you want it to be "tough," you might find that by the time you add a motor, a fuel tank, and two of your friends, the gunwales are only two inches above the waterline. That’s a death trap. Weight is the enemy. Professional designers like the late Phil Bolger specialized in "instant boats" that used thin, light materials in clever geometries to provide strength without the bulk. Following a proven plan is better than "eyeballing it" every single time.

The Epoxy Nightmare You Aren't Prepared For

Let’s talk about the sticky reality. Epoxy resin is the magic juice of modern boatbuilding, but it is also a temperamental, expensive, and potentially allergenic mess.

📖 Related: Draft House Las Vegas: Why Locals Still Flock to This Old School Sports Bar

You have to get the mix ratio perfect. If it calls for a 2:1 ratio and you go 2.1:1 because you were careless with the measuring cup, the resin might stay tacky forever. It will never cure. You’ll have a sticky, useless hull that you can't sand and can't paint. Also, "amine blush" is a real thing—a waxy film that forms on the surface of curing epoxy which will cause your next layer of paint or resin to peel right off if you don't wash it with water and a Scotch-Brite pad.

Tools You Actually Need (And Ones You Don't)

You don't need a $5,000 table saw.

- A decent jigsaw: This is your primary tool for cutting hull panels.

- A random orbital sander: You will spend 70% of your time sanding. If you buy a cheap one, your hands will be numb for a week.

- Plastic spreaders: For the epoxy. Buy a hundred of them.

- A sharp block plane: Essential for "fairing" or smoothing out the edges of your plywood so the fiberglass tape sits flat.

Safety and the "Coast Guard" Reality

If you are building a motorized boat in the United States, you need to be aware of the U.S. Coast Guard safety standards. Even for a home-built boat, you usually need a Hull Identification Number (HIN) to get it registered and insured. This often involves an inspection where they check for things like level flotation. If your boat flips, will it stay at the surface or head for the bottom? This is why many DIY builders incorporate "buoyancy tanks" or pour-in expanding foam under the seats. It’s not just a good idea; it’s often the law.

The "Fairing" Phase: Where Spirits Go to Die

"Fairing" is the process of making the hull perfectly smooth. When you first finish the fiberglassing, the boat will look lumpy and rough. To fix this, you mix epoxy with "microballoons" (tiny hollow glass spheres) to create a paste that's the consistency of peanut butter. You smear this over the hull and then sand it back.

👉 See also: Dr Dennis Gross C+ Collagen Brighten Firm Vitamin C Serum Explained (Simply)

Then you do it again.

And again.

This is the point where most people quit. The boat is technically "done" in their minds, but it looks like a basement project. If you want it to look like a professional boat, you have to embrace the dust. Wear a respirator. Not a cheap paper mask—a real P100 rated respirator. Fiberglass dust and epoxy vapor are no joke for your lungs.

The Big Misconception About Cost

Is it cheaper to make your own boat?

Mostly, no.

By the time you buy marine plywood ($100+ per sheet), gallons of epoxy ($150+ per gallon), fiberglass cloth, marine-grade paint, hardware, and safety gear, you could have probably bought a very decent used aluminum fishing boat on Craigslist. You build a boat because you want the experience and a specific design that you can't buy at a dealership. You do it for the geometry and the soul of the craft.

Actionable Next Steps for the Aspiring Builder

- Start with a "Puddle Duck Racer" or a simple pirogue: Do not try to build a 25-foot cabin cruiser as your first project. Build something under 10 feet first to master the stitch-and-glue technique.

- Buy a set of plans from a reputable designer: Look at Bateau, Glen-L, or Devlin Designs. Do not try to draw your own lines unless you understand naval architecture.

- Set up a climate-controlled space: Epoxy will not cure properly if it's 40 degrees Fahrenheit in your garage. You need a consistent 60-70 degree environment.

- Order a "sample kit" of epoxy and fiberglass: Before you commit to a $2,000 lumber order, practice glassing two scraps of wood together to see if you actually have the patience for the process.

- Join a community: The WoodenBoat Forum is an invaluable resource where crusty experts will tell you exactly why your idea for a "cardboard reinforced hull" is a disaster before you spend a dime on it.

Making a boat is a lesson in patience and precision. It's about measuring three times and cutting once, only to realize you were looking at the wrong side of the tape measure anyway. But the first time you push off from the shore and realize the floorboards are staying dry, every hour of sanding becomes worth it.