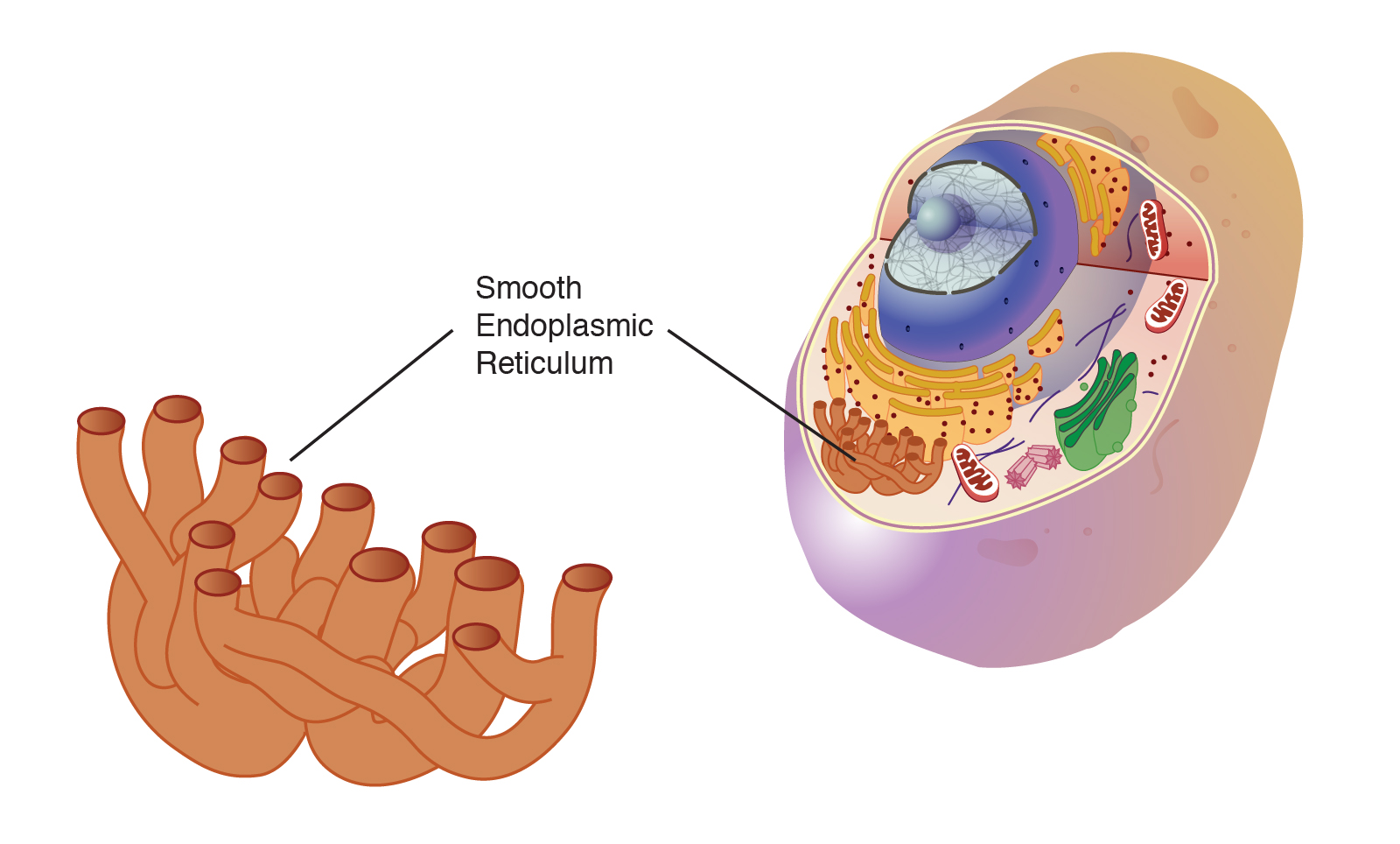

If you look at enough smooth endoplasmic reticulum images, you start to realize something kind of funny. Most biology textbooks do us a massive disservice. They usually show this neat, little pile of tubes tucked away next to the nucleus, looking almost like a stack of coral or maybe some weirdly organized pasta. It looks static. Frozen.

But it isn’t. Not even close.

In a living cell, the Smooth ER (SER) is a chaotic, writhing network of membranes. It’s a shapeshifter. When you’re looking at a high-resolution electron micrograph, you aren't just seeing a "part" of the cell; you’re looking at the cell’s primary manufacturing floor, its detox center, and its calcium vault all rolled into one. If the Rough ER is the factory for proteins, the Smooth ER is the chemical refinery that keeps the whole operation from exploding.

Why Modern Microscopy Changes How We See the Smooth ER

For decades, we relied on thin-section electron microscopy. You take a cell, freeze it or fix it in resin, slice it incredibly thin, and blast it with electrons. The resulting smooth endoplasmic reticulum images are classic—mostly circular or tubular cross-sections.

However, researchers like Dr. Jennifer Lippincott-Schwartz at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute have used 3D super-resolution microscopy to show us that the SER is actually a continuous, highly dynamic "lumen" or space. It’s a single organelle. Think of it like a massive, interconnected subway system where the tunnels are constantly being rebuilt while the trains are still running.

When you look at a static image, you miss the "tubule fission." That’s a fancy way of saying the tubes are constantly snapping apart and fusing back together. This movement is powered by the cytoskeleton. Without those tiny molecular motors (dynein and kinesin) dragging the SER membranes along microtubules, your cells couldn't distribute lipids or signal each other properly. Honestly, a still photo of the SER is like a photo of a hurricane; it tells you where it is, but it doesn't tell you what it's doing.

The Tube vs. The Sheet

One of the biggest distinctions you'll see in high-end imaging is the difference between the "sheets" of the Rough ER and the "tubules" of the Smooth ER.

The Rough ER has ribosomes stuck to it—those are the little dots you see in pictures. These ribosomes need flat surfaces to do their work. But the Smooth ER? It’s all about surface area for enzymes. By forming into intricate tubes, the SER can pack an incredible amount of membrane into a tiny space. This is crucial because the SER is where your body builds lipids.

If you're looking at smooth endoplasmic reticulum images from a liver cell (hepatocyte), the SER looks like a dense jungle. Why? Because the liver is your body's primary detox center. It needs all that membrane surface area to host cytochrome P450 enzymes. These enzymes are the heavy hitters that break down drugs, alcohol, and metabolic waste.

[Image comparing rough and smooth endoplasmic reticulum structures]

The SER Isn't Just "Smooth"—It's Specialized

It’s easy to think the Smooth ER is the same in every cell. It’s not.

📖 Related: Why the Radius of Moon in Meters is Weirder Than You Think

In your muscles, the SER is so specialized we give it a different name: the Sarcoplasmic Reticulum (SR). If you look at images of the SR, it doesn't look like a random pile of tubes. It’s organized into a precise wrap around the muscle fibers (myofibrils).

- Calcium Storage: The SR is packed with calcium ions.

- The Trigger: When a nerve signal hits the muscle, the SR dumps that calcium instantly.

- The Reset: Then, it pumps it all back in.

If you see an image where the SER looks like a lattice-work cage around a long rod, you’re likely looking at muscle tissue. This isn't just a "lipid factory" anymore; it’s a high-speed electrical-to-mechanical transducer.

Then there are the cells that make hormones. Take the adrenal glands or the Leydig cells in the testes. If you pull up smooth endoplasmic reticulum images from these areas, the SER is massive. It has to be. Steroid hormones like testosterone and estrogen are derived from cholesterol, and the enzymes that convert cholesterol into these hormones live right on the SER membrane.

Misconceptions About Color and Shape

Let's get one thing straight: cells don't have colors.

When you see those vibrant pink, blue, or neon green smooth endoplasmic reticulum images, those are false-color images. In a standard Electron Microscope (EM), everything is grayscale. Scientists add color later to help distinguish between different structures.

Sometimes, people see "whorls" in SER images. These are concentric circles of membrane that look like a fingerprint. For a long time, people thought these were artifacts—basically mistakes made while preparing the slide. We now know that these whorls can actually be a sign of "ER stress." When a cell is overwhelmed by toxins or a massive demand for lipid production, the SER can actually reorganize itself into these strange, circular patterns to try and cope.

How to Read an Electron Micrograph of the SER

If you’re trying to identify the SER in a real scientific image (not a textbook drawing), here is what you need to look for.

First, find the nucleus. Usually, the ER is nearby. Look for a bunch of lines. If the lines have little black dots on them, that's the Rough ER. Keep following those lines away from the nucleus. Eventually, the dots disappear, and the lines start looking more like "circles" or "ovals." These are actually tubes that have been sliced crosswise. That is your Smooth ER.

🔗 Read more: how many people use an iphone: The 2026 Reality Check

The SER is often found in close proximity to mitochondria. This isn't an accident. They actually form "Mitochondria-Associated Membranes" (MAMs). These are physical bridge-points where the SER and mitochondria trade lipids and calcium. It’s basically a high-speed data and fuel line between the cell's power plant and its refinery.

In high-resolution smooth endoplasmic reticulum images, you can sometimes see these "tethering proteins" that hold the two organelles together. It's incredibly tight—we're talking a gap of only 10 to 30 nanometers.

The Role of SER in Human Disease

When the SER doesn't look right in images, it’s usually a sign of trouble.

Neurological disorders like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s are often linked to "ER Stress." In these cases, the SER can appear fragmented or swollen in images. Because the SER is responsible for calcium signaling, when it breaks down, the cell loses its ability to communicate.

Another example is Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD). In images of liver cells affected by NAFLD, you’ll see massive lipid droplets—big, white empty-looking circles—crowding out the SER. The SER is actually responsible for creating the coating (phospholipids) for these fat droplets. When the system is overloaded, the SER gets pushed to the periphery, and its tubular network starts to break down.

Key Visual Indicators of SER Health:

- Tubule Diameter: Should be relatively uniform.

- Connectivity: A healthy SER is a "reticulum" (a net), not a bunch of isolated bubbles.

- Proximity to Organelles: Look for its "handshake" with the mitochondria and Golgi apparatus.

Actionable Insights: Moving Beyond the Image

Understanding smooth endoplasmic reticulum images is more than just a biology exercise. It’s about understanding how your body handles stress and toxins on a molecular level.

If you are a student or a researcher, stop looking at 2D diagrams. Seek out 3D tomograms or "Focused Ion Beam Scanning Electron Microscopy" (FIB-SEM) data. These give you a volumetric view. You can actually see the "three-way junctions" where three tubes meet—a hallmark of a healthy, functioning SER network.

For those interested in health and longevity, the SER is a major player in "autophagy." This is the process where your cell cleans out junk. There is a specific type called "ER-phagy," where the cell actually eats and recycles damaged parts of its own Endoplasmic Reticulum.

To support your SER health:

- Watch your lipid intake: Since the SER is the lipid factory, high levels of saturated fats can trigger the "ER stress response."

- Manage oxidative stress: The enzymes in the SER produce free radicals as a byproduct of detoxification. Antioxidants help mitigate this.

- Understand drug interactions: Many medications are processed by the SER. Taking multiple drugs that use the same cytochrome P450 pathway can "clog" the SER's processing capacity.

Basically, the next time you see one of those smooth endoplasmic reticulum images, don't just see a bunch of tubes. See a dynamic, shifting, vital refinery that is currently working overtime to keep you alive.

Check out the latest datasets on the Protein Data Bank or the Cell Image Library to see real-world, high-resolution SER captures that go beyond the textbook.