Big is better. That’s the lie we’ve been fed for about seventy years. We are obsessed with "economies of scale," giant multinational mergers, and GDP numbers that go up while the actual quality of life for the average person feels like it’s sliding down a muddy hill.

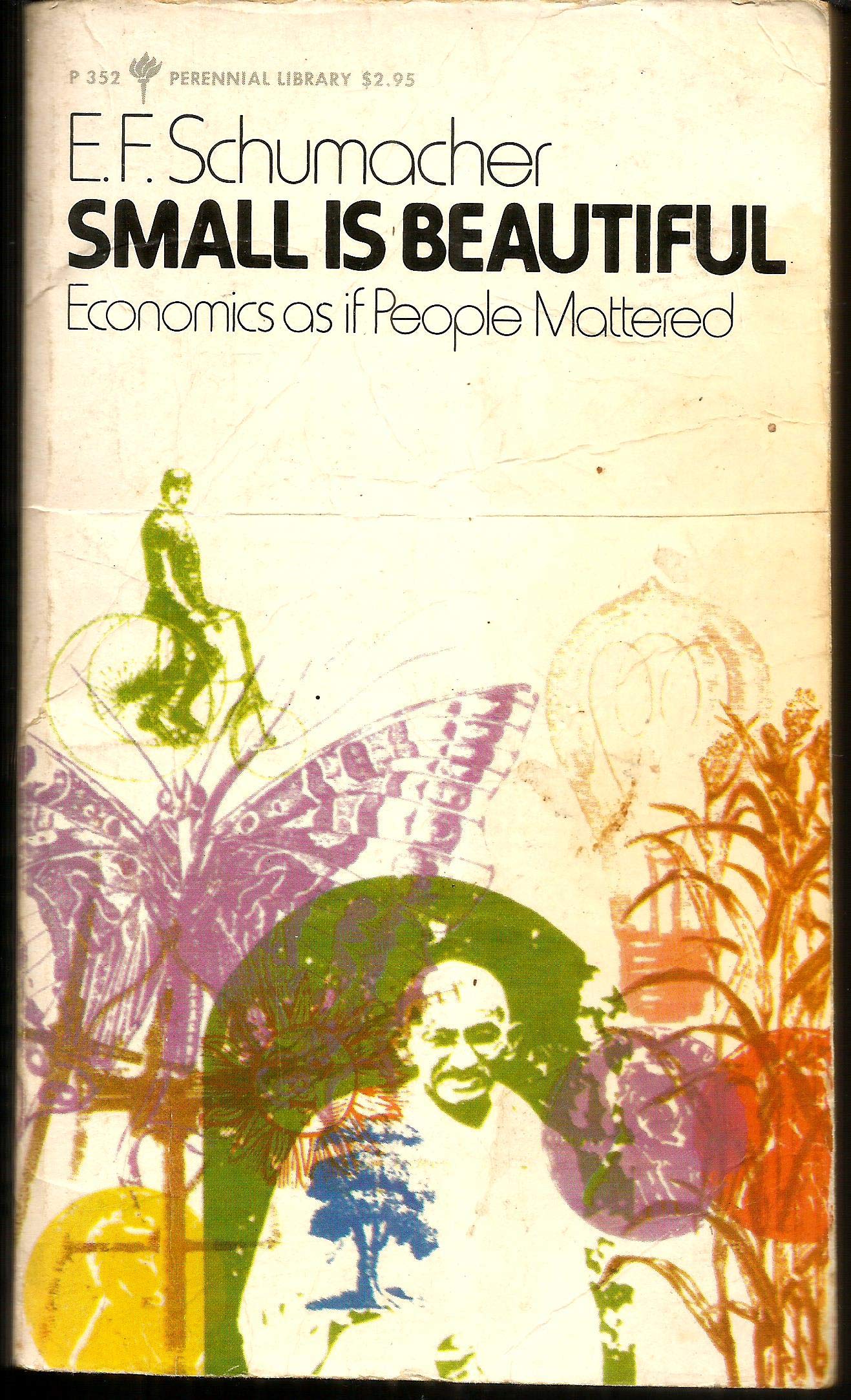

Ever felt like just a cog? You aren't alone. In 1973, an eccentric German-British economist named E.F. Schumacher published a collection of essays that basically called "bullsh*t" on the entire direction of modern industrial society. He titled it Small Is Beautiful: Economics as if People Mattered. It wasn't just a book; it was a manifesto against the "bigger is better" cult.

Schumacher wasn't some hippie dreamer. He was the Chief Economic Advisor to the UK National Coal Board. He understood the gears of industry better than almost anyone, yet he spent his later years arguing that our current economic system is "sustainable" in the same way a bonfire is sustainable—it looks great until you run out of wood.

The Problem With "Giantism"

We live in an era of massive things. Massive cities. Massive corporations. Massive bureaucracies. Schumacher argued that this "giantism" is actually a form of pathology. When things get too big, they stop being human-scale. You lose the "person" in the process.

🔗 Read more: St Louis County Real Estate Information: What Most People Get Wrong

Think about your local coffee shop versus a global chain. At the local spot, the owner probably knows your name. They buy milk from a local dairy. The money stays in the town. In the giant chain, you’re a data point. The manager is a middle-man following a PDF sent from a corporate office three time zones away. This is exactly what Schumacher meant by small is beautiful economics as if people mattered. He believed that once an organization exceeds a certain size, it loses its soul and starts treating humans like mere factors of production—interchangeable parts like nuts and bolts.

The logic of modern economics is centered on "more." More growth. More consumption. But Schumacher pointed out something incredibly obvious that we all seem to forget: we live on a finite planet. You can't have infinite growth on a finite rock. It’s physically impossible. He famously compared modern man to a person living on "capital" rather than "income," treating the Earth’s natural resources (like fossil fuels and biodiversity) as a bank account we can drain forever without ever making a deposit.

Buddhist Economics: A Different Way to Measure Success

One of the most famous chapters in the book explores "Buddhist Economics." Now, don't let the name throw you off if you aren't spiritual. Schumacher used the term to contrast with "Materialist Economics."

In the West, we define success by how much we consume. If you buy a new car every two years, the GDP says you’re a hero. If you fix your old car and keep it for twenty years, the GDP thinks you’re a failure. It’s backwards. Schumacher argued that the goal of economics should be to obtain the maximum amount of well-being with the minimum amount of consumption.

Imagine that for a second.

Instead of working 60 hours a week to buy stuff you don't have time to use, you work 20 hours a week because your needs are simpler and your community provides what you need. In this framework, "work" isn't a "necessary evil" or a "utility" to be minimized by automation. Instead, work is a way for a human to develop their faculties, join with others in a common task, and bring forth goods and services needed for a becoming existence.

💡 You might also like: Stimulus Payment Eligibility 2025: What Most People Get Wrong

He saw three functions of work:

- To give a person a chance to utilize and develop their faculties.

- To enable them to overcome their ego-centeredness by joining with others.

- To bring forth the goods and services needed for a becoming existence.

If your job is just pushing a button or staring at a spreadsheet that means nothing to you, the system has failed, regardless of how high your salary is. Honestly, look around. We have higher "wealth" than ever, but anxiety and depression are through the roof. Schumacher saw this coming fifty years ago.

Intermediate Technology: Helping, Not Replacing

When Schumacher visited India and Burma, he realized that Western "aid" was often destructive. We’d send a multi-million dollar automated tractor to a village that didn't have a mechanic or spare parts. When the tractor broke, it became a giant rust bucket, and the farmers were worse off than before because they'd forgotten how to use their old tools.

He proposed "Intermediate Technology."

This is technology that is vastly superior to the primitive tools of the past but much simpler and cheaper than the "giant" technology of the rich. It’s technology that people can actually own and fix themselves. Think of a hand-cranked grain mill versus a massive industrial processing plant. The hand-cranked mill empowers the local community; the massive plant makes them dependent on a corporation.

Today, we see this in the "Right to Repair" movement. When Apple or John Deere makes it impossible for you to fix your own device, they are practicing the "giantism" Schumacher hated. When people build open-source hardware or localized solar grids, they are practicing small is beautiful economics as if people mattered.

The Ghost of the 1970s in 2026

It’s weirdly prophetic. Schumacher talked about the energy crisis long before it was a daily news headline. He argued that a system built on cheap, non-renewable energy was a house of cards.

Today, as we face climate change and the "loneliness epidemic," his words feel like a cold bucket of water to the face. We’ve tried the "big" way. We’ve tried the "globalize everything" way. And while it brought cheap plastic toys to our doorsteps via Amazon, it also hollowed out the middle class and destroyed the social fabric of small towns.

Critics often say Schumacher's ideas are "anti-progress." That’s a lazy take. He wasn't against technology; he was against technology that enslaves the user. He wasn't against trade; he was against trade that destroys local self-reliance. He was basically the original advocate for "Localism."

Real-World Examples of Small Economics

You can see this philosophy alive today, even if the people doing it haven't read the book.

Look at the Mondragon Corporation in Spain. It's a federation of worker cooperatives. It's huge, yes, but it’s owned by the workers. Decisions are made democratically. It’s an attempt to keep the "person" at the center of the business.

Look at Community Land Trusts (CLTs). Instead of housing being a speculative asset for Wall Street firms, the land is owned by the community to keep housing permanently affordable. This is a direct application of Schumacher’s idea that land is a sacred trust, not just a commodity to be exploited.

Consider Micro-Grids. Instead of relying on one massive, vulnerable power plant, neighborhoods are installing their own solar and battery storage. It’s resilient. It’s small. It’s beautiful.

How to Apply "Small is Beautiful" to Your Life

You don't have to overthrow the global financial system to start living "as if people mattered." It’s about a shift in perspective.

First, look at your consumption. Do you actually need more, or do you need better? Choosing a hand-crafted tool that lasts thirty years over a plastic one that lasts three is a Schumacher-style move.

Second, look at your work. If you’re a business owner, are you trying to grow as fast as possible, or are you trying to create a "human-scale" environment where your employees actually enjoy their lives? Sometimes, the best thing a business can do is stay small. Growth for the sake of growth is the ideology of the cancer cell.

Third, look at your community. Buy local. Not because it’s a trendy slogan, but because it’s an act of economic self-defense. When you buy from a neighbor, you are strengthening the web of relationships that makes life worth living.

Actionable Insights for a Human-Scale Future

To move toward an economy that actually serves us, we have to stop worshiping the "Gross National Product" and start looking at "Gross National Happiness" (a concept famously adopted by Bhutan). Here is how you can practically pivot toward these principles:

1. Prioritize Resilience over Efficiency

The "just-in-time" supply chain is incredibly efficient until a boat gets stuck in the Suez Canal or a pandemic hits. Then it collapses. A "small is beautiful" approach favors "just-in-case" resilience. Grow a garden. Learn a trade. Support local farmers.

2. Seek "Appropriate" Solutions

Before buying a high-tech solution to a problem, ask if a simpler, "lower" technology would work better. Do you need a smart-fridge that tells you when you're out of milk, or do you just need to look in the fridge? High-tech often adds layers of complexity and "un-freedom" (subscription fees, data tracking) that we don't actually need.

3. Support Decentralization

Whenever you have a choice, support the decentralized option. Use a local credit union instead of a "too big to fail" bank. Use decentralized web protocols. Support local zoning laws that protect small businesses from "big box" predators.

4. Redefine "Standard of Living"

Schumacher challenged us to see that a high standard of living is not the same as a high level of consumption. A high standard of living includes clean air, a sense of belonging, meaningful work, and time for leisure. If you have a million dollars but no time to see your kids, you are, by Schumacher's metrics, quite poor.

The core of small is beautiful economics as if people mattered is the realization that we are not just "consumers" or "labor units." We are people. And any economic system that forgets that is eventually going to fail us. It’s time to stop trying to fix the giant machines and start building things that are small enough to care about.