If you want to understand where Prince, D'Angelo, and Outkast actually came from, you have to look at 1973. Specifically, you have to look at the Sly and the Family Stone Fresh album. It’s a weird record. It’s lean. Compared to the sprawling, drug-fueled paranoia of There’s a Riot Goin’ On, Fresh feels like a man trying to pull himself together by sheer force of will, even while the world around him was twitching.

Sly Stone was a genius in trouble by the early seventies. Everyone knows the stories. He was missing shows. He was carrying around a violin case that definitely didn't have a violin in it. But in the middle of that chaos, he stripped the Family Stone sound down to the bone. He didn't just write songs; he engineered a new kind of rhythmic skeleton.

The New Soul of the Sly and the Family Stone Fresh Album

Most people think of "Thank You (Falettinme Be Mice Elf Agin)" when they think of Sly's funk. That's the blueprint. But the Sly and the Family Stone Fresh album took that blueprint and bleached it. It’s dry. There’s almost no reverb on the drums. Andy Newmark, a white kid who replaced the legendary Greg Errico, brought a "straight-ahead" feel that was metronomic but swung like a gate in the wind.

Take a track like "In Time." It’s arguably the most influential five minutes of funk ever recorded. Miles Davis was obsessed with it. Legend has it he made his band listen to it for hours on end. Why? Because the pocket is so deep it’s practically a canyon. Sly’s vocals aren't even singing half the time; he’s grunting, whispering, and punctuating the beat. He used his voice as a percussion instrument.

Then there’s the lineup shift. Larry Graham, the man who basically invented the slap bass, was gone. He’d moved on to Graham Central Station after things got too heavy with Sly’s "enforcement" crew. Rusty Allen stepped in on bass for Fresh, and while he didn't have Graham's thunder, he had this rubbery, melodic agility that allowed the songs to breathe.

Why the Minimalism Worked

The early Family Stone records were psychedelic explosions. They were "Everyday People" and "Stand!"—bright, communal, and loud. By 1973, that hippie optimism was dead. Fresh reflects that. It's music for a small room. It’s intimate. It’s also incredibly difficult to play. If you've ever tried to cover "If You Want Me to Stay," you know the bassline is a marathon of ghost notes and syncopation.

✨ Don't miss: The Lil Wayne Tracklist for Tha Carter 3: What Most People Get Wrong

- It rejected the wall-of-sound production common in the early 70s.

- Sly played many of the instruments himself, overdubbing until it felt right.

- The album features a cover of Doris Day’s "Que Sera, Sera (Whatever Will Be, Will Be)," which sounds less like a pop standard and more like a soulful prayer for survival.

The Songs That Defined a Decade

"If You Want Me to Stay" is the hit. It’s the one everyone knows. It’s got that iconic, wandering bassline that seems to ignore the rest of the song until it doesn't. Sly’s vocal performance here is peak "late-period Sly"—he’s raspy, effortless, and sounds like he’s leaning against a lamppost at 3:00 AM.

But "Babies" is the sleeper hit. It’s fast. It’s frantic. It’s got these sharp horn stabs that feel like they’re poking you in the ribs. It captures the frantic energy of New York and LA in the seventies—a kind of nervous sunshine.

And we have to talk about "Skin I'm In." It’s a self-reflection. It’s Sly acknowledging his own identity and the pressures of being a Black superstar in a country that wanted him to be a caricature. The rhythm is relentless. It’s a precursor to the "naked" funk that would define the Minneapolis sound a decade later. Honestly, without the Sly and the Family Stone Fresh album, there is no Sign o' the Times.

The Miles Davis Connection

It's not an exaggeration to say this album changed jazz. Miles Davis was transitioning into his electric period, and he was looking for a way to make his music "heavier." He saw in Sly a way to stay relevant. Miles reportedly said that "In Time" was the baddest thing he'd ever heard. He wasn't talking about the melody. He was talking about the space between the notes.

Sly understood that funk isn't about what you play; it’s about what you don’t play. He left huge gaps in the arrangements. That silence creates a tension that makes the listener lean in. It's a psychological trick as much as a musical one.

🔗 Read more: Songs by Tyler Childers: What Most People Get Wrong

What Most People Get Wrong About Fresh

There’s a narrative that Fresh was the start of the decline. People say Sly was too "out of it" to lead a band. That’s a total misunderstanding of the work. If you listen to the multi-tracks, you hear a producer in total control. He was meticulous. He was obsessive. He was a perfectionist who happened to be struggling with addiction, but the music on this record is anything but sloppy.

In fact, compared to Riot, Fresh is almost disciplined. It’s catchy. "Que Sera, Sera" was a massive risk, but Rose Stone’s vocal delivery turns it into a gospel-inflected masterpiece. It’s the heart of the album. It provides a moment of warmth in an otherwise cool, detached landscape.

Technical Brilliance in the Studio

Sly was using the studio as an instrument before it was cool. He used early drum machines (like the Maestro Rhythm King) on Riot, but on Fresh, he integrated live drums with such precision that they felt machine-like. This "human-machine" hybrid is the foundation of modern hip-hop production.

- Vocal Layering: Sly would stack his own voice to create a choir effect that sounded both ghostly and powerful.

- Dry Signal: He avoided the "big" drum sound of the era, opting for a tight, dead room sound that cut through radio speakers.

- The Mix: Notice how the vocals are often tucked into the mix rather than sitting on top of it. You have to work to hear the lyrics sometimes.

The Lasting Legacy of the 1973 Masterpiece

When you listen to D'Angelo's Voodoo, you are listening to the Sly and the Family Stone Fresh album. When you listen to Erykah Badu or Kendrick Lamar’s more experimental tracks, you’re hearing the echoes of 1973. It’s the "musician’s album."

It didn't have the massive cultural "unity" hits of the late sixties. It didn't have a "Stand!" or an "Everyday People." Instead, it gave us a blueprint for how to be cool when the world is falling apart. It's a record about resilience. It’s about being "fresh" even when you’re tired.

💡 You might also like: Questions From Black Card Revoked: The Culture Test That Might Just Get You Roasted

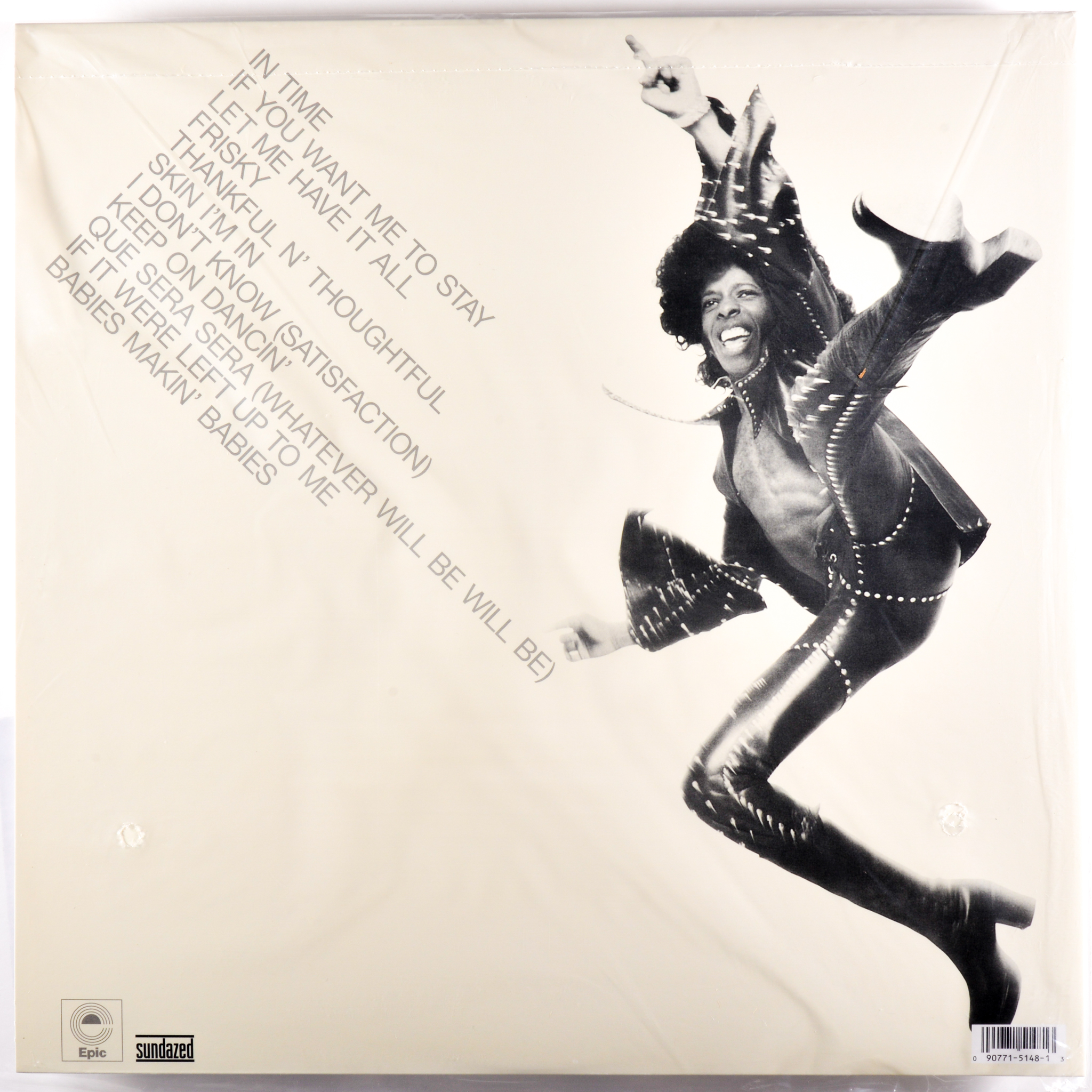

The cover art says it all. Sly is mid-leap. He’s in a gold suit. He looks like he’s defying gravity. In a way, he was. He was at the end of his tether, yet he managed to jump higher than almost anyone else in the industry. It’s a miracle the record exists at all, given the state of the band at the time.

Actionable Insights for Music Lovers

If you want to truly appreciate this album, don't just stream it on your phone speakers. Do these three things to get the full experience:

- Listen on Headphones: You need to hear the panning. Sly moves instruments around the stereo field in ways that were very advanced for 1973. The way the hi-hat sits in your ear on "In Time" is crucial.

- Compare to Riot: Play There's a Riot Goin' On first, then play Fresh. Notice the shift from "muddy and dark" to "clean and sharp." It’s one of the greatest tonal shifts in any artist's discography.

- Focus on the Bass: Even if you aren't a musician, try to follow the bassline of "If You Want Me to Stay" from start to finish without getting distracted by the vocals. It’s a masterclass in melodic counterpoint.

- Research the Personnel: Look up the work of Sister Rose (Rose Stone). Her contribution to the vocal textures on this album is often overshadowed by Sly’s genius, but she is the glue that holds the harmonies together.

The Sly and the Family Stone Fresh album isn't just a relic of the seventies. It’s a living document. It’s a reminder that even in our most fragmented moments, we can create something tight, disciplined, and beautiful. It taught us that "less is more" isn't just a cliché—it's a rhythmic philosophy.

To truly understand the evolution of Black music in America, you have to sit with this record. You have to let it itch. It's not always comfortable, but it is always brilliant. Go back and give "In Time" another spin. You'll hear something new every single time. That is the definition of a masterpiece.