Money talks. In Britain, it doesn't just talk; it uses a dizzying array of nicknames, historical leftovers, and Cockney rhyming slang that leaves most tourists—and honestly, plenty of locals—scratching their heads. If you’ve ever been in a London pub and heard someone mention a "score" or a "bullseye," you weren't witnessing a darts match. You were hearing slang for money uk in its natural habitat. It’s a language born from the street markets of the East End, the shadows of the betting shops, and a long history of pre-decimal coinage that refuses to die.

British culture is obsessed with not being too "on the nose" about wealth. Talking about "Great British Pounds" feels stiff. Cold. A bit too much like a bank manager in a pinstripe suit. Instead, we use words that feel more lived-in.

The weird truth about the Monkey and the Pony

Ask a Londoner how much a "monkey" is, and they’ll tell you £500 without blinking. Why a monkey? It’s not because of some weird zoo-based barter system. It actually traces back to the British Raj in India.

The 500 Rupee note featured an image of a monkey. When soldiers and traders returned from India to the London docks, they brought the term with them. It stuck. The same goes for a "pony," which is £25. The 25 Rupee note had a pony on it. These terms are deeply ingrained in the betting world. If you’re at the races and you hear someone putting a "pony on the nose," they’re risking twenty-five quid on a specific horse to win.

It’s strange when you think about it. We’re using currency slang from a colonial era to describe modern digital transactions. You might even see a "monkey" mentioned in a WhatsApp group about splitting a holiday rental.

The Quid and the Sovereign

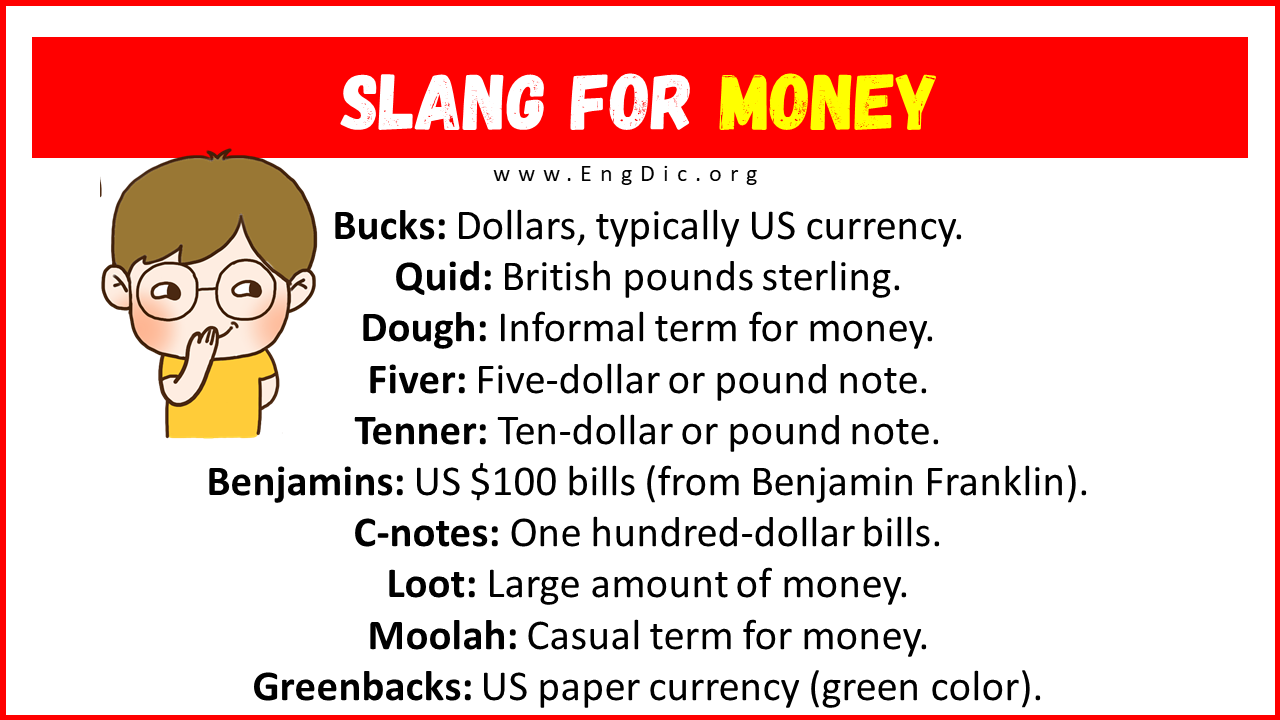

The word "quid" is the undisputed king of slang for money uk. It’s so common that it almost isn't slang anymore. You’ll hear it in the boardroom and the chippy.

Where did it come from? Most linguists point toward the Latin phrase quid pro quo—meaning "something for something." It’s been around since the late 1600s. Unlike "pounds," you never say "quids" in the plural when you’re giving a specific amount. It’s "ten quid," never "ten quids." If someone says "quids in," they mean they’ve made a tidy profit.

Then you have the "nicker."

🔗 Read more: Why Everyone Is Still Obsessing Over Maybelline SuperStay Skin Tint

"That’ll be two nicker, mate." It sounds aggressive, but it’s just another word for a pound. It likely comes from the "nickel" used in foreign exchanges or perhaps linked to the "nicker" horse, though that's more of a reach. The point is, British money slang is rarely logical. It’s vibes-based.

Cockney Rhyming Slang: More than just "Apples and Pears"

If you want to understand slang for money uk, you have to get your head around rhyming slang. It’s a linguistic game. You take a common phrase, find a rhyme for the word you actually want to say, and then—this is the tricky part—you usually drop the rhyming word.

Take "Lady Godiva." It rhymes with "fiver" (£5).

So, a five-pound note is a "Lady."

"Can you lend us a Lady?"

Then there’s the "Pavarotti." Tenner. Get it? Tenor. Luciano Pavarotti was the world’s most famous tenor. This is a relatively modern addition compared to the Victorian-era slang, showing that British slang is a living, breathing thing that absorbs pop culture.

Some other classics you’ll hear:

- A Blue: A five-pound note (because they are literally blue).

- A Darwin: A tenner (back when Charles Darwin was on the back of the note).

- A Bullseye: £50. This comes from the 50 points you get for hitting the bullseye in darts.

- A Score: £20. This is just old English. A score has meant twenty since the days of the King James Bible.

The "Grand" and the "Large"

When we get into the thousands, the slang becomes a bit more international, but with a British twist. "A grand" is £1,000. Everyone knows that. But did you know people also call it a "bag"? This comes from "a bag of sand," which rhymes with "grand."

"He wants three bags for that car."

💡 You might also like: Coach Bag Animal Print: Why These Wild Patterns Actually Work as Neutrals

It sounds like a drug deal. It’s usually just a used Ford Fiesta.

The term "large" is also creeping in from American TV, but "grand" remains the heavyweight champion of the four-figure bracket. Interestingly, "K" (from the Greek kilo) is used almost exclusively in professional or digital contexts. You’ll see "£30k" in a job advert, but you’d rarely hear someone say, "I owe him five K" in a pub. They’d say "five grand." Or "five bags."

Why does this even matter?

You might think this is all just a bit of fun for "Only Fools and Horses" fans. But slang is a social gatekeeper. Using the right slang for money uk signals that you’re part of a community. It’s about trust. In the markets of Portobello Road or the East End, using these terms isn't just about being "cool." It’s about showing you know how the world works. You aren't a "mug" (someone easily fooled).

There’s a certain grit to it. Money in the UK is often tied to class and geography. A "bob" was a shilling in pre-decimal currency (before 1971). Even though the shilling has been gone for over fifty years, you’ll still hear older people say "a few bob" to mean a bit of money. "He’s got a few bob, him," implies someone is secretly wealthy.

The Digital Shift: Is slang dying?

We live in a world of Monzo cards and Apple Pay. We rarely touch physical cash anymore. Does anyone still care about a "Lady Godiva" when they’re just tapping a piece of plastic against a glowing reader?

Surprisingly, yes. Slang is adapting.

We’re seeing new terms emerge. "Squid" instead of "quid" (just a silly phonetic play). "Sheets" for notes. The language is shifting from the physical appearance of the money—like "a blue"—to the digital representation of it. However, the heavy hitters like "quid," "grand," and "pony" aren't going anywhere. They are too embedded in the British psyche. They carry a weight that "twenty-five pounds" just doesn't have.

📖 Related: Bed and Breakfast Wedding Venues: Why Smaller Might Actually Be Better

Real-world examples of money slang in action

If you’re trying to navigate a conversation in the UK, context is everything. Here is how these terms actually land in a chat:

- The Pub Setting: "It’s my shout. Only cost a tenner anyway." (A tenner is £10).

- The Car Deal: "I’ll give you two bags and a monkey, cash today." (£2,500).

- The Small Loan: "Can you lend us a score until Friday?" (£20).

- The Brag: "He’s making fifty bags a year and still complains." (£50,000).

Notice how the numbers are often dropped. It’s not "a five pound tenner," it’s just "a tenner." It’s efficient. It’s fast. It’s British.

What you need to know next

Understanding British money slang isn't just a party trick. It helps you understand the culture of the UK. We are a nation that loves to hide the "real" meaning behind layers of history and rhyming jokes.

If you want to use this slang without looking like you’re trying too hard, start small. Use "quid." Everyone uses "quid." Don't jump straight into "Lady Godivas" and "Bags of Sand" unless you’re actually in a cockney pie and mash shop. You’ll look like you’re auditioning for a Guy Ritchie movie.

Actionable Steps for Navigating UK Money Talk:

- Stick to "Quid" first: It’s the safest, most universal term. Use it for any amount from £1 to £1,000,000.

- Learn the "Tenner" and "Fiver": You will use these every single day. If someone asks for a "five," they might mean the coin or the note, but "fiver" always means the note.

- Listen for the "Grand": When discussing salaries or cars, "grand" is the standard. Avoid saying "thousands" unless you’re reading a formal report.

- Observe the "Monkey" and "Pony": Use these only in casual, familiar settings. They are very common in the south of England but might get a weird look in the far north.

- Watch out for Pre-Decimal Hangover: If an older person mentions "a bob" or "a tanner," they’re talking about pennies and shillings. Just interpret it as "a small amount of change."

The next time you’re in London and you hear someone complaining about losing a "ton" (£100) on a bet, you’ll know exactly what they mean. You aren't just hearing words; you’re hearing the history of Indian trade, Victorian street slang, and the peculiar British desire to never call a spade a spade—especially when that spade costs twenty quid.