Drawing a door seems easy until you actually try to do it. You think, "It’s just a rectangle, right?" Then you sit down with a pencil, and suddenly the angles look like a funhouse mirror, the handle is floating three feet too high, and the whole thing looks like it’s sliding off the paper. It’s frustrating. Honestly, most people fail at a sketch of a door because they draw what they think a door looks like instead of what’s actually in front of them.

Doors are deceptive. They are these massive, heavy objects that we interact with dozens of times a day, yet we rarely look at the joinery or the way light hits the recessed panels. If you want to get better at architectural sketching, you have to stop treating the door as a flat object. It’s a 3D volume that sits inside another 3D volume—the wall.

The Vanishing Point Trap

The biggest mistake is the perspective. If you’re standing directly in front of a door, sure, it’s a rectangle. But who draws a door perfectly head-on? That’s a blueprint, not a sketch. To make it feel real, you’re usually looking at it from a slight angle. This is where linear perspective comes in, and where most hobbyists lose the plot.

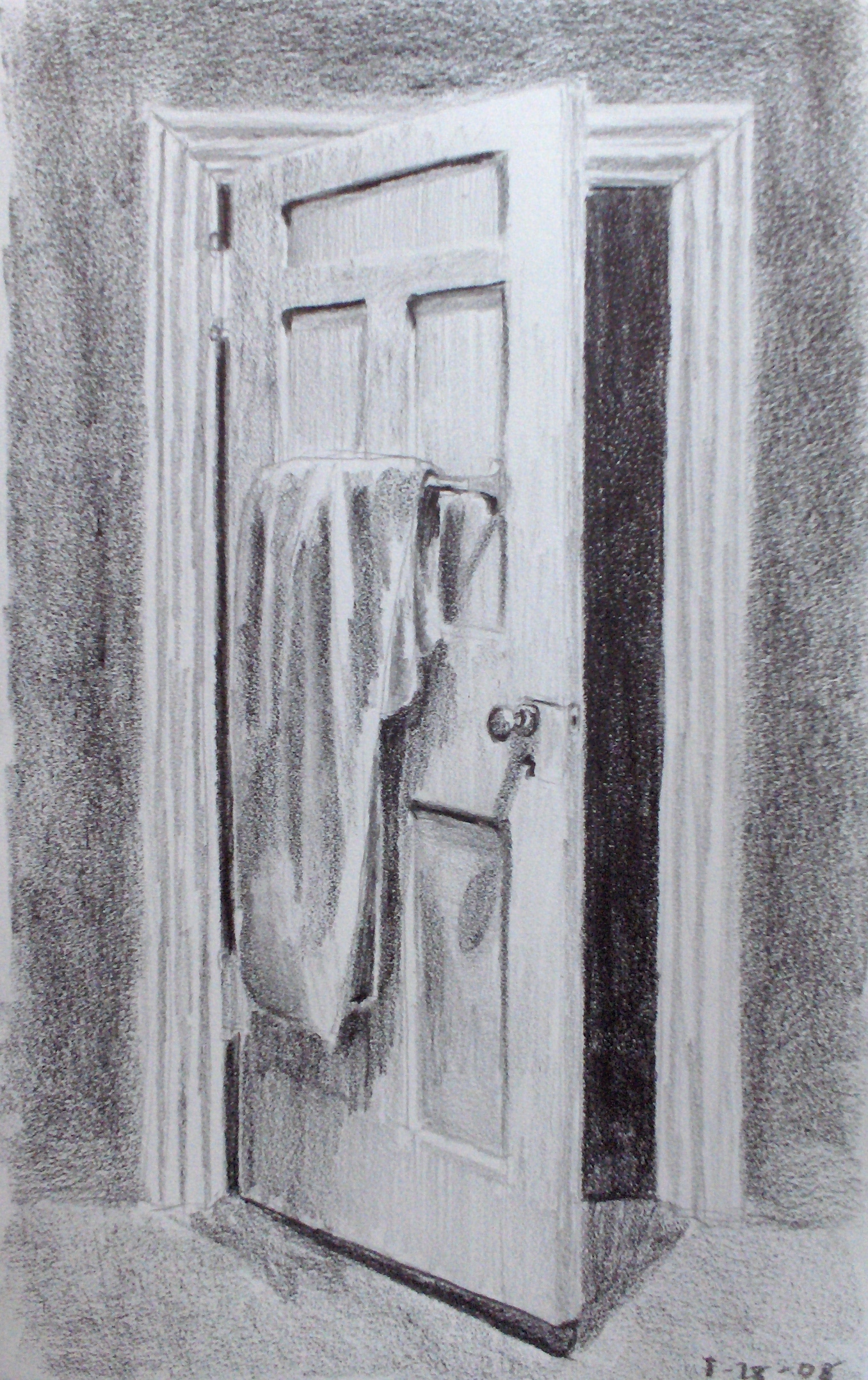

If the door is slightly open, you aren’t dealing with one set of vanishing points anymore. You’re dealing with two. The door frame follows the perspective of the room, but the door itself—the swinging slab of wood—has its own independent vanishing point because it’s rotated on a hinge. This is why your sketch of a door often looks "broken" or "skewed." The lines of the door top and the floor aren't parallel in a 3D space; they are converging.

Think about the "eye level" or horizon line. If your sketch feels like the door is looming over you or falling away, check where your horizon line sits. If you’re sitting on a chair, your eye level is probably about 3 to 4 feet off the ground. Every horizontal line above that level must angle down toward the vanishing point. Every line below it must angle up. It sounds academic, but it’s the difference between a doodle and a drawing that feels like you could walk through it.

It’s All About the "Reveal"

Go look at a door frame right now. Look closely at where the wood meets the wall. You’ll see a tiny edge, maybe only a quarter-inch wide, where the frame sticks out or sits back. In the art world, we call this the "reveal."

If you just draw a line for the door and a line for the wall, it looks paper-thin. Real doors have thickness. A standard interior door is usually $1 \frac{3}{8}$ inches thick, while exterior doors are $1 \frac{3}{4}$ inches. In a sketch of a door, you have to show that thickness on the hinge side or the top edge if the door is ajar. Without that sliver of a side plane, the door looks like a piece of cardboard.

✨ Don't miss: The Truth About Man Having Oral Sex With a Woman: What Most People Get Wrong

Then there's the casing—the trim around the door. It’s not just a flat border. It has shadows. It casts a shadow on the wall, and the door itself casts a shadow on the frame. If you ignore these tiny gaps of darkness, the door won't look "set" into the wall. It’ll just look like it’s floating on the surface.

Anatomy of the Slab: Don't Guess

Standardization is your friend here. Most doors follow specific proportions. If you’re sketching a standard American door, it’s likely 80 inches tall. The width varies, but 30 or 36 inches is the norm.

If you are sketching a six-panel door—the kind you see in every suburban house—the placement of those panels isn't random. The middle rail (the horizontal part) is usually positioned right where the doorknob goes. This is roughly 36 inches from the floor. If you put your door handle at the vertical midpoint of the door, it’s going to look bizarrely high. We are used to seeing handles at waist height.

Common Door Components to Include:

- The Stiles: These are the vertical boards.

- The Rails: The horizontal boards (top, lock, and bottom). Note that the bottom rail is almost always wider than the top one to provide visual "weight."

- The Jamb: The inner part of the frame that the door closes against.

- The Threshold: That bump on the floor you trip over.

When you start your sketch of a door, block these out as simple boxes first. Don't worry about the wood grain or the fancy brass handle yet. Get the "skeleton" right. If the skeleton is deformed, the prettiest shading in the world won't save it.

Lighting and the "Puddle" of Shadow

Doors are great for practicing value contrast. Because a door is usually recessed into a wall, it’s a giant shadow-catcher. Even in a well-lit room, the top of the door frame usually has a dark line where the header blocks the overhead light.

If the door is cracked open into a dark room, you get that "classic noir" look—a sharp, vertical wedge of pitch black. But if the light is coming from inside the room, you get a "spill" on the floor. To make your sketch look professional, don't just shade the door; shade the floor around it. A door doesn't exist in a vacuum. It interacts with the ground.

Draw the "puddle" of shadow cast by the door slab. If the door is open at a 45-degree angle, the shadow on the floor will be a distorted version of that rectangle. Use a softer pencil, like a 4B or 6B, for the deepest part of the crack between the door and the jamb. That "dead black" line is what creates the illusion of depth.

Materials and Texture

Wood grain is a trap. Beginners often spend hours drawing every single line in the oak grain, and it ends up looking like a mess of hair.

👉 See also: Ancient Greek Columns Explained (Simply): How to Actually Tell Them Apart

Instead, think about the sheen. Is it a high-gloss painted door? Then it should have sharp, white highlights where the light hits the edges of the panels. Is it old, weathered barn wood? Then you want jagged, broken lines and "pitting."

For a realistic sketch of a door made of wood, only draw the grain in the areas where the light transitions into shadow. Leave the brightest parts mostly white. The human brain is incredibly good at filling in the gaps; if you draw a little bit of grain near the corners, the viewer will assume the whole door has grain. You don't need to be a printer.

Real-World Practice: The "Sketching in the Wild" Method

Don't just draw from your head. Go to a local historic district or even a hardware store. Look at how different doors are constructed.

A heavy, Victorian-style door has deep "shadow pockets" because the moldings are so thick. A modern, minimalist door is all about the "negative space"—the thin, perfect gap between the slab and the frame. If you're struggling with a sketch of a door, try drawing only the "negative space" (the shadows and the gaps) and see if the door emerges on its own.

🔗 Read more: Can You Return Costco Without Receipt? What Really Happens at the Membership Counter

Practical Steps for Your Next Sketch

- Find your eye level. Mark it lightly on the paper. This dictates every angle you draw.

- Box it out. Draw the "hole" in the wall first. Then draw the door slab as a separate box.

- Check your doorknob height. It should be about 36 inches (or roughly $1/3$ of the way up from the bottom).

- Add the "Reveal." Give the door and the frame some thickness. Avoid single lines.

- Focus on the hinge gap. That dark, vertical line is what makes the door look like it can actually swing.

- Shadow the panels. If it's a paneled door, the light usually hits the top and left "inside" edges of the recessed part, while the bottom and right edges stay in shadow.

The next time you sit down to work on a sketch of a door, remember that you’re drawing an architectural transition, not just a shape. Focus on the weight, the depth, and the way the object sits in the frame. Get the perspective right, and the rest is just decoration.