You’ve been there. You sit down with a fresh sheet of paper, a 2B pencil, and a clear vision of a graceful profile or a piercing gaze. Ten minutes later, you’re staring at something that looks vaguely like a potato with eyes. It’s frustrating. It’s also totally normal. Most people think sketch female face drawing is about some magical "talent" you’re born with, but honestly, it’s mostly just geometry and deprogramming your brain from drawing what it thinks it sees versus what is actually there.

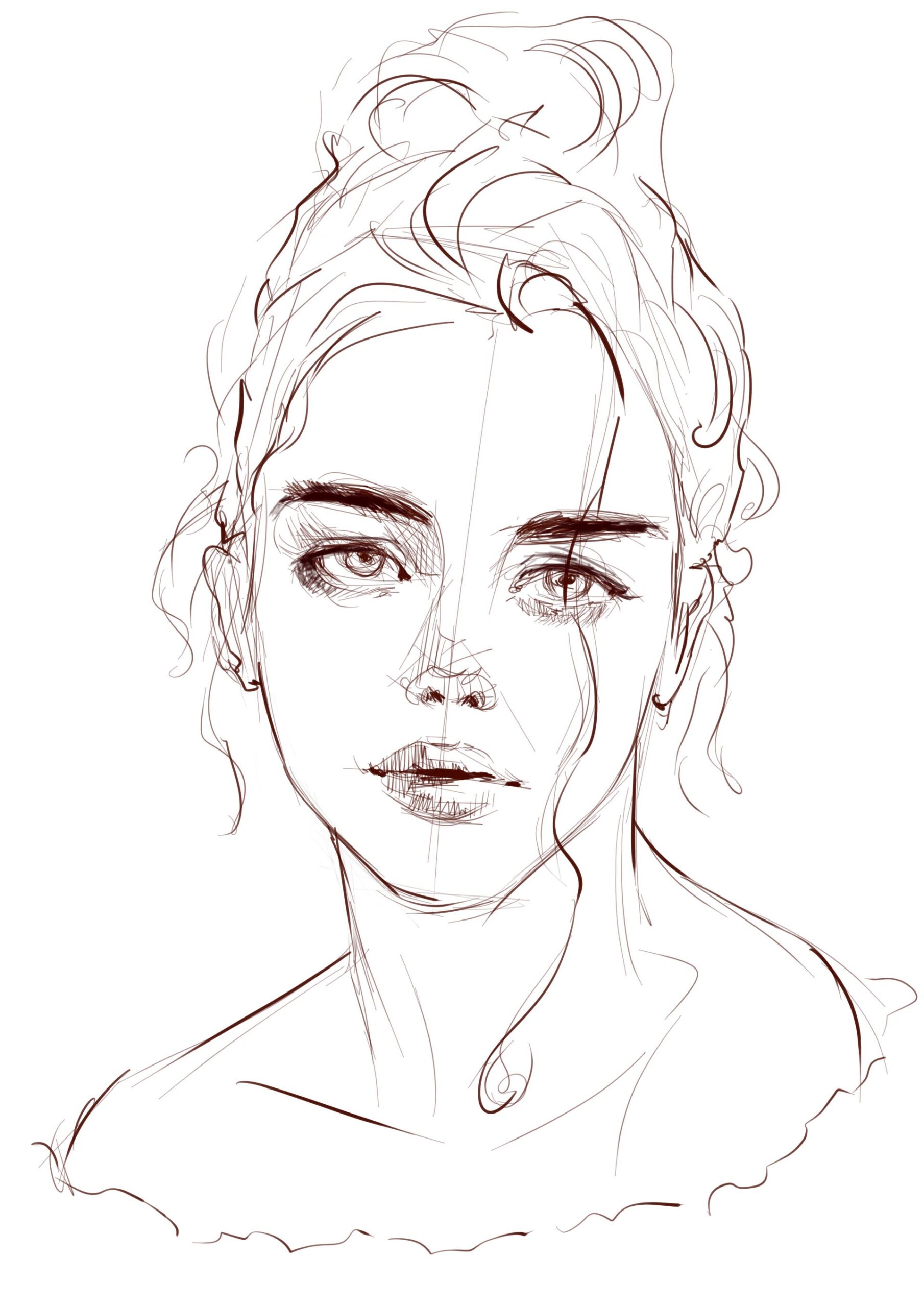

Drawing women’s faces specifically comes with a unique set of hurdles. There is a traditional emphasis on softness, certain rhythmic flows of the hair, and subtle transitions in bone structure that can make or break the realism of the piece. If you push the shadows too hard, she looks aged. If you make the jawline too sharp, the "feminine" aesthetic—if that’s what you’re going for—shifts into something more masculine or stylized. It is a delicate balancing act of precision and restraint.

The Loomis Method Is Not Optional

If you want to get serious about a sketch female face drawing, you have to talk about Andrew Loomis. His 1943 book, Drawing the Head and Hands, is basically the Bible for illustrators. He figured out that the human head isn't a circle; it’s a sphere with the sides sliced off.

Think about that.

The cranium is a ball. When you slice the sides off, you create a flat plane for the temples. This is where most beginners fail. They draw a flat oval and try to "sticker" the features onto it. Instead, you need to establish the "brow line" and the "center line" of the face immediately. For female subjects, Loomis often suggested slightly more refined proportions—perhaps a narrower chin or a more delicate bridge of the nose—but the underlying architecture is exactly the same as any other human.

Real mastery comes from understanding the "Rule of Thirds" in facial proportions. Generally, the distance from the hairline to the eyebrows, the eyebrows to the bottom of the nose, and the nose to the bottom of the chin are roughly equal. If you mess this up by even a few millimeters, the face looks "off," and you won't know why. You'll keep erasing the eyes, thinking they’re the problem, when the real issue is that the forehead is three inches too tall.

Stop Drawing Individual Eyelashes

Seriously. Stop it.

💡 You might also like: Human DNA Found in Hot Dogs: What Really Happened and Why You Shouldn’t Panic

One of the biggest mistakes in a sketch female face drawing is the "spider leg" effect. You know exactly what I mean. You draw the eye, and then you draw twenty individual, identical lines sticking out from the eyelid. It looks terrifying. In reality, eyelashes clump together. They create a dark, thick line at the base of the lid. If you look at the work of master portraitists like John Singer Sargent, he barely drew individual hairs. He drew shapes of shadow.

The eye itself is a ball sitting inside a socket. The skin of the eyelids wraps around that ball. If you don't shade the whites of the eyes (the sclera), they will look like glowing marbles. They should almost always be slightly darker than the paper because they sit under the shadow of the upper lid and the brow. It’s these tiny, counter-intuitive details that separate a "doodle" from a professional-grade sketch.

The Nose Is A Lie

The nose isn't actually a shape. It's a suggestion. Most people try to draw the "lines" of the nose, but the nose has very few hard lines. It’s mostly just a collection of soft gradients and a couple of dark spots for the nostrils.

- Focus on the "under-plane" of the nose. This is the shadow cast toward the lips.

- Keep the bridge of the nose light. A heavy line down the side of the nose will instantly make the face look ten years older or much more "rugged" than intended.

- The "ball" of the nose is where your highlight lives. Keep it clean.

Softness vs. Structure in Female Portraits

There is a huge debate in the art world about "feminizing" features. Some artists argue that to draw a woman, you must round every corner. Others, like the legendary Stan Prokopenko (Proko), teach that you still need to understand the skull underneath. If you ignore the zygomatic bone (the cheekbone), the face will look like a bag of flour.

The trick is the "edge quality."

In a sketch female face drawing, you want a mix of "hard" and "soft" edges. A hard edge might be the crease of the eyelid or the line where the lips meet. A soft edge is the transition from the cheek to the jaw. If you make every edge hard, she looks like a wooden puppet. If every edge is soft, she looks like she’s melting in the sun. You have to find that middle ground where the structure is visible but the surface feels like skin.

📖 Related: The Gospel of Matthew: What Most People Get Wrong About the First Book of the New Testament

Dealing With Hair Without Losing Your Mind

Hair is usually where people give up. They start with great intentions and then end up scribbling a "haystack" on top of the head.

Don't draw hair. Draw "masses."

Imagine the hair is a big piece of fabric draped over the head. Find the "shadow side" and the "light side" of that fabric. Only after you have the big shapes should you go in with a sharp pencil and add a few "stray" hairs to give the illusion of detail. You don't need to draw 10,000 lines. You just need to draw ten lines in the right places.

Basically, the brain is lazy. If you give it a few convincing textures at the edges and in the highlights, it will fill in the rest and assume the whole head of hair is detailed. Use this to your advantage. It saves time and prevents your sketch from looking cluttered.

The Mental Game of Symmetry

Nobody's face is symmetrical. If you use a ruler to make both eyes perfectly identical, the portrait will look "uncanny valley"—it’ll be creepy. One eye is always slightly higher. One side of the mouth curls a bit more. These "imperfections" are actually what make a sketch female face drawing look like a real person and not a mannequin.

When you’re working from a reference photo, flip both the photo and your drawing upside down. This is an old trick from Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain by Betty Edwards. By turning it upside down, your brain stops seeing an "eye" and starts seeing a "curved shape of grey." It bypasses your analytical mind and lets you draw what is actually there. It’s a bit of a trip the first time you do it, but the results are usually shocking.

👉 See also: God Willing and the Creek Don't Rise: The True Story Behind the Phrase Most People Get Wrong

Practical Steps for Your Next Sketch

Stop looking for the perfect pencil. It doesn't exist. You can do a world-class sketch female face drawing with a Ticonderoga #2 if you understand values.

First, get your "lay-in" right. This is the light, ghost-like outline of the head and features. Spend 50% of your time here. If the lay-in is wrong, the shading won't save it. You can't polish a bad foundation.

Second, identify your light source. If the light is coming from the top right, every single shadow should be on the bottom left. Consistency is more important than "accuracy." If your shadows are inconsistent, the viewer's brain will know something is wrong, even if they can't articulate what it is.

Third, use a kneaded eraser. Not the pink ones on the end of the pencil—those just smudge. A kneaded eraser lets you "pick up" graphite to create highlights in the hair or the glint in the eye. It's a subtractive drawing tool, and it's a game-changer.

Lastly, walk away. When you’ve been staring at a drawing for two hours, you become "blind" to your own mistakes. Go get a coffee. Look at a tree. Come back twenty minutes later, and the errors will jump off the page at you.

Drawing isn't about hand-eye coordination as much as it is about learning how to see. Most people look, but they don't see. They see a nose; an artist sees a series of planes reflecting light at different angles. Once you make that mental shift, the "sketching" part becomes secondary. It just becomes a matter of recording your observations.

Keep your pencils sharp, your paper clean, and for heaven's sake, stop drawing those individual eyelashes. You’ve got this. Just keep moving the pencil.

Next Steps for Mastery:

Focus your next practice session exclusively on the "planes of the head." Before trying a full portrait, draw five small spheres and practice shading them to look like three-dimensional balls. Then, move on to sketching just the "eye masks"—the area from the brow to the top of the cheek—to understand how the eyes sit within the skull. This isolated practice builds the "muscle memory" needed for more complex, full-face compositions.