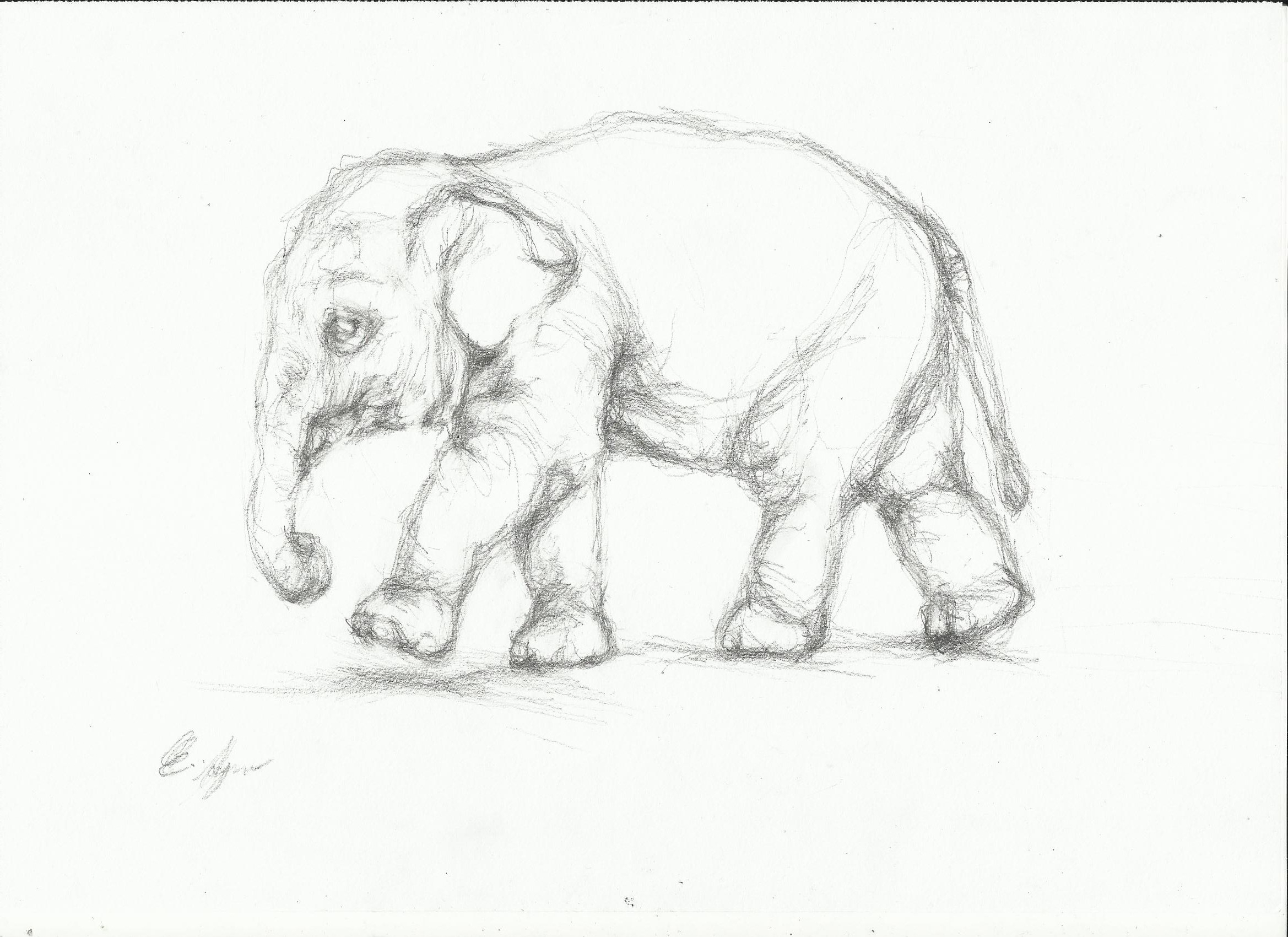

You want to sketch an elephant. Most people start with a big gray blob and four tree trunks. It ends up looking like a lumpy potato. Honestly, that’s because we think we know what an elephant looks like, but our brains are lying to us. We see "big" and "heavy" and we forget the actual architecture underneath all that wrinkled skin. If you want to get this right, you have to stop drawing a "character" and start drawing a skeletal system. It sounds boring. It's actually the secret.

I've spent years watching artists struggle with the sheer scale of the African elephant (Loxodonta africana). They get the ears right—those massive, map-of-Africa shapes—but then the legs look like they’re glued onto the side of the body. They don't feel the weight. An adult bull can weigh over 13,000 pounds. You have to draw that gravity. If the feet aren't planted firmly, the whole sketch falls apart. You're not just drawing lines; you're managing thousands of pounds of imaginary pressure.

The skeletal framework that changes everything

Stop looking at the skin. Seriously. Look at the spine. When you sketch an elephant, the highest point isn't the head; it’s the hump of the back, especially in African elephants. Asian elephants (Elephas maximus) have a twin-domed head and a different spinal curve. If you mix these up, anyone who knows their wildlife will spot it instantly.

The shoulder blade is a massive, triangular plate. It moves. When the elephant walks, that shoulder pushes up and down under the skin.

You need to start with two massive circles. Think of them as the ribcage and the hips. But don't make them perfect circles. Nature hates a perfect circle. Make them slightly squashed ovals. The ribcage is significantly larger than the pelvic area. Connect them with a line that represents the spine. This isn't just a guide; it's the bridge that holds the whole animal together. If that bridge is too long, your elephant looks like a dachshund. Too short? It’s a pug.

Why the legs aren't just cylinders

People draw elephant legs like pipes. They aren't. They’re more like human legs than you’d think, just encased in thick padding. The "knee" on the front leg is actually the wrist. The real elbow is way up high, tucked near the chest. If you don't account for that bend, the leg looks stiff. It looks dead.

Think about the feet. Elephants are essentially walking on their tiptoes. There is a massive fatty pad behind the toe bones that acts like a shock absorber. This is why they can walk almost silently despite their size. When you sketch the foot, don't just draw a flat bottom. Give it that slight "heel" lift. It adds a sense of motion and realism that a flat cylinder just can't provide.

Nailing the trunk and the head structure

The trunk is the most complex part. It has over 40,000 muscles. Think about that. Forty thousand. You aren't going to draw all of them, obviously, but you need to show the tension. The trunk isn't a wet noodle. It has structure. It has rings.

The trunk's "C" curves

When sketching the trunk, use overlapping "C" curves. This creates the illusion of those muscular segments. Don't make the lines straight. Follow the wrap-around of the muscle. And remember the "finger" at the end. African elephants have two opposable extensions at the tip of the trunk; Asian elephants only have one. It’s a tiny detail, but it’s the difference between a generic drawing and a professional study.

The head is a heavy, bony box. It’s not a circle. There are deep depressions at the temples. If you don't shade those hollows, the head looks like a balloon. The eyes are surprisingly small. They sit tucked away behind the heavy brow bone. This protects them from thorns and brush. When you place the eye, align it with the top of the ear attachment point. If it’s too high, the elephant looks surprised. Too low, and it looks like it’s melting.

The texture of age and environment

Skin is where most artists go overboard. They draw every single wrinkle. Don't do that. You’ll end up with a mess that looks like a topographical map of the moon. Instead, focus on the "stress points." Wrinkles happen where the skin folds: the armpits, the neck, and where the trunk meets the face.

The skin isn't just gray. It's a canvas of mud, dust, and scars. Elephants use their environment to protect themselves from the sun. If you’re sketching a real elephant, look for the patches where they’ve been wallowing.

💡 You might also like: Why Pictures of Jack Russell Terrier Dogs Always Look So Chaotic

Use varied line weights. Thick, heavy lines for the underbelly where the shadows are deepest. Thin, wispy lines for the sparse hairs on the tail and the chin. This variety creates "visual interest." It keeps the viewer's eye moving. If every line is the same thickness, the drawing feels flat and digital. You want it to feel organic. You want it to feel like it could breathe.

Handling the tusks

Tusks are just overgrown teeth. They emerge from the upper jaw. This means they aren't just stuck onto the face; they are rooted in the skull. Draw the base of the tusk bulging slightly under the skin of the lip. This shows the weight and the "growth" of the ivory. Also, tusks aren't perfectly symmetrical. One is often shorter—the "master" tusk—because the elephant uses it more for digging or stripping bark. Adding a slight chip or an uneven length makes your sketch feel like it has a history.

Common mistakes you're probably making

I see this all the time: the "floating elephant." Because they are so heavy, their feet often sink slightly into the grass or sand. If you draw the feet sitting perfectly on top of a flat line, the elephant looks like it's made of cardboard. Scribble in some grass overlapping the toes. Add a heavy shadow directly beneath the belly. This "grounds" the animal.

Another big one? The ears. People draw them like floppy dog ears. Elephant ears have a complex network of veins that help dissipate heat. They also have a very rigid cartilage structure at the top. They don't just hang; they are held. When an elephant is alert, those ears fan out like sails. Use sharp, jagged lines for the edges where the ears might have been torn by acacia thorns. It adds character. It tells a story of survival.

Actionable steps for your next sketch

Don't start with a pencil. Start with your eyes. Watch some high-definition footage of elephants in the wild. Look at how the skin bunches up when they turn their heads. Notice the way their weight shifts from one side to the other when they stand still.

- Step 1: The Gesture. Draw a quick, 30-second scribble of the elephant's posture. Don't worry about details. Just get the "flow" of the body.

- Step 2: The Core Volumes. Sketch in those two big ovals for the ribcage and hips. Connect them with the spinal arch.

- Step 3: The Columnar Legs. Block in the legs as thick, sturdy pillars, making sure to mark the "wrist" (front knee) and the actual hind knee.

- Step 4: The Head Box. Shape the skull as a rectangular volume, noting the temple hollows and the trunk base.

- Step 5: The Wrap-around. Add the trunk using overlapping curves to show muscle volume.

- Step 6: Refinement. This is where you add the ears, tusks, and those deep, localized wrinkles.

If you really want to level up, try sketching without looking at your paper for a few minutes. It forces your hand to follow what your eye actually sees, not what your brain thinks it sees. This "blind contour" method is the fastest way to break bad habits.

Forget about making it "pretty." A sketch is a way of asking a question about a shape. If the first one looks like a weird rhinoceros-hippo hybrid, that's fine. Do ten more. Change the angle. Draw one from behind. Draw one from a low "worm's eye" view to emphasize the scale. The more you understand the anatomy, the less you'll have to rely on "tricks" to make it look real.

Go grab a 2B pencil or a chunk of charcoal. Find a photo of an African elephant from the Amboseli National Park—they have some of the most iconic tuskers in the world. Look at the way the sunlight hits the top of the back. Now, start with the spine. Forget the trunk for a minute. Just get that heavy, magnificent frame down on the paper. The rest will follow naturally once the foundation is solid. Focus on the weight, the gravity, and the sheer presence of the animal. That’s how you truly sketch an elephant.